10 Historical Figures Who Schemed Their Way to the Top

Murder. Corruption. Fear. Seduction. Betrayal. Some historical figures stopped at nothing to reach the top.

Murder. Corruption. Fear. Seduction. Betrayal. Some historical figures stopped at nothing to reach the top.

Table of Contents

ToggleBeing at the top is a great feeling. Some people will go to extreme lengths to get there through seduction, lying, betrayal, nepotism or even murder. Below are ten historical figures who went from the shadows to the top by way of their plotting and scheming.

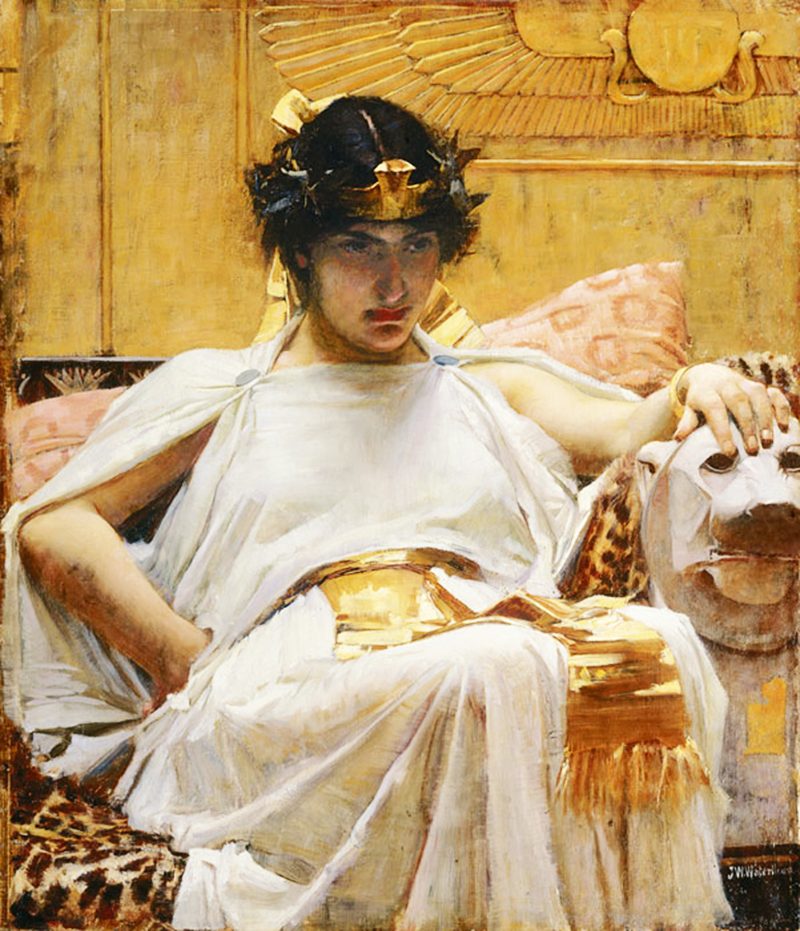

Cleopatra, the last Ptolemaic pharaoh and ruler of ancient Egypt, is often portrayed as a schemer and seductress. But she’s far more than that — she took her role as ruler of Egypt seriously and would go to any means necessary to protect her kingdom. Cleopatra was also a polymath and contributed to the Library of Alexandria, studying various subjects, including medicine.

Her double marriage to Julius Caesar and her brother and co-ruler Ptolemy XIV (Egypt allowed polygamy) meant she also influenced Roman administrative affairs. Caesar’s death in 44 BC on the Ides of March enabled their son, Caesarion, to rule alongside his mother. She was now at the epicenter of Roman politics, and to solidify her power, she started an affair with Mark Anthony.

Cleopatra’s romances were not purely passions of the flesh but rather political strategies to keep the favor of the Romans because Egypt was financially strained. Her legacy is hotly debated to this day. Still, she’s more than just a seductress — she went to the lengths necessary to save her kingdom.

Joseph Stalin (1878–1953) grew up poor in a small town called Gori, Georgia, then a part of the Russian Empire. After school, he joined the Marxist Social Democratic movement, the Bolsheviks, under Lenin’s leadership. He was also involved in various criminal activities, including bank heists to help fund the Bolshevik efforts. Multiple arrests between 1902 and 1913, imprisonment, and exile to Siberia did not break his revolutionary spirit.

Serving under Lenin and appointed in 1922 as secretary general of the Central Committee’s Communist Party. Upon Lenin’s death in 1924, he engaged in political maneuvering and leveraged his political alliances to transform the ostensibly minor role of Secretary General into the absolute leader of the Soviet Union.

Stalin was not afraid to eliminate anyone that stood in his way, and during the mid-1930s, the Great Purge proved he meant business. He is estimated to be responsible for the deaths of six to 20 million people — either through executions or indirectly through his policies (like the Holodomor famine).

Tomas Wolsey (ca. 1473–1530) is commonly believed to be the son of a butcher. Wolsey wormed his way into King Henry VIII’s court as the King’s almoner in 1509 when Henry took the throne. Wolsey was savvy enough to align his views with the King, who was seeking men for the Privy Chamber who shared his goals.

Wolsey’s fall came in 1529 when he failed to secure an annulment of Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon. As a result, he was stripped of all his government titles, and lost his magnificent palace, Hampton Court. In addition, Wolsey was made to answer treason charges — a favorite tactic of Henry VIII to deal with opposition.

Zhao Gao (died 207 B.C.E.) was an official, politician, and calligrapher from the Chinese Qin dynasty. His family was distantly related to Zhao state’s royal family of the Warring States period. Due to his knowledge in law, he served as a close aide of the Qing dynasty’s three rulers — Qin Shi Huang (Shihuangdi), Qin Er Shi, and Ziying.

In a plot with minister Li Si, Zhao forged a letter commanding Emperor Shihuangdi’s eldest son (Fusu), named heir apparent in the letter, to commit suicide. The letter also ordered the same of generals and brothers Meng Tian, Fusu’s aide, and Meng Yi. Their families were also killed.

The emperor’s other son, Hu Hai (Qin Er Shi), ascended to the throne, and Zhao and Li Si ruled behind the scenes. Later, he also convinced Hu Hai to commit suicide. Zhao and Li turned on each other, and Zhao had Li executed. Zhao installed Ziying of Qin as king over a fragmented Qin empire. Ultimately, Zhao was killed in an assassination ordered by Ziying who only ruled for 46 days at the time.

Mathilde Kscessinska (1872–1971) was attracted to royalty and handsome men. She was a ballerina, born in Ligovo near St. Petersburg in Russia. She received her first lessons from her father and graduated from the Imperial Ballet School in 1890.

She was the mistress of Tsarevich Nicholas II of Russia between 1890 and 1894. She met Nicholas at the ballet school’s graduation dinner in 1890. The relationship ended with Nicholas’s engagement and marriage to Princess Alix of Hesse and by Rhine. After Nicholas’ wedding, he asked his cousin Grand Duke Sergei Mikhailovich (1869–1918) to look after Mathilde, and he provided generously for her.

Sergei also used his influence to help promote her career at the Mariinsky Ballet. She was appointed prima ballerina assoluta of the Mariinsky Ballet, probably due to her connection to the Grand Duke. Although she was not in love with Sergei, he cared for her. She then pursued a relationship with Grand Duke Andrei Vladimirovich, whom she later married while exiled in Paris.

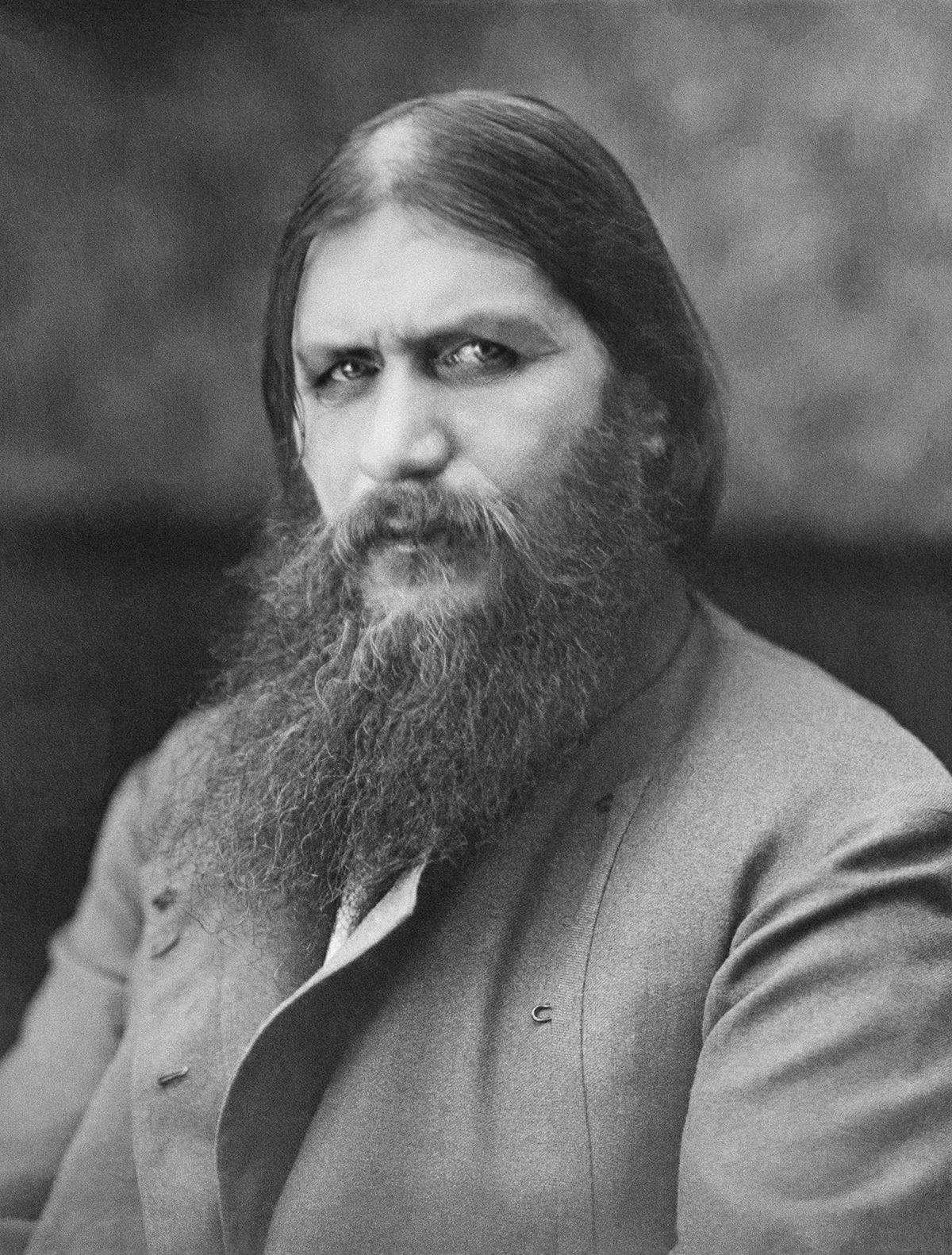

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (1869–1916) trained as a monk but left the church. He was born into a peasant family, and little is known about his early life. He married Praskovya Dubrovina in Siberia in 1887, and they had nine children, but only three survived into adulthood. In 1897 he had a sudden renewed interest in religion. He undertook several pilgrimages to the Holy City. He traveled to the Middle East and Greece while his wife remained in Pokrovskoye, loyal to him until her death.

His wanderlust took him to St. Petersburg in 1903, arriving with the reputation that he was a faith healer and mystic; two years later, he was introduced to the Romanovs. He conned his way into the palace, and the tsarina’s undying trust, by seemingly ‘curing’ Alexei’s hemophilia.

When Nicholas II left to go and fight in WW I, Rasputin de-facto ruled the country through Tsarina Alexandra. He was murdered in 1916 after causing much damage to the royal family’s reputation and even the whole of Russia.

Born into slavery Toussaint L’Ouverture (1743–1803) led a successful slave revolt and ruled over the colony of Saint Dominque (later Haiti). On the ‘Night of Fire,’ August 22, 1791, he was inspired to help other enslaved people in their cause.

He developed a reputation as a capable soldier leading guerilla attacks during the insurgency following the Night of Fire. First, he allied with Spain, which was attempting to control the island and oust France. When France emancipated all Black enslaved persons in the empire in 1794 and declared they had citizenship rights, he allied with France again between 1794 and 1802. He was the dominating military and political leader, operating under his self-appointed title General-in-Chief of the Army.

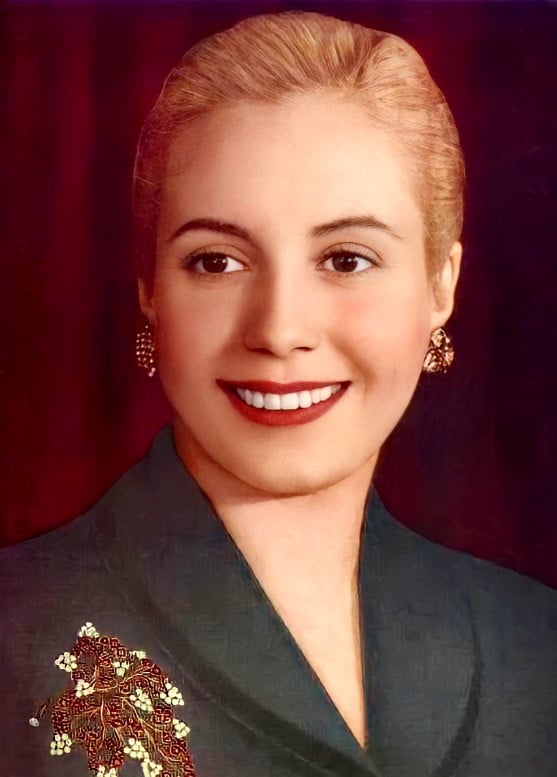

Evita Perón (1919–1952) came from humble beginnings — her family was her father’s ‘second’ family and shunned after his death by his legal wife and family. Being the ‘illegitimate’ family offspring, she and her family lived in poverty.

She grew into a famous actress who caught the eye of Juan Perón, a widower, in 1944. She promptly became his girlfriend and First Lady of Argentina when he was voted in as president the following year. She was intelligent, articulate, and charismatic — qualities that certainly helped Juan’s political race to the top and her aspirations.

Evita used her influence to fight for causes she believed in such as women’s suffrage and the plight of the poor. She was the de facto leader of the labor and health ministries in Juan’s government.

Genghis Khan (1162–1227 C.E.) was born into a minor Mongolian tribe. He rose to head of his clan and secured loyalty through alliances with other clans. His method? Exterminate their nobility and assimilate the clan into his own. Another tool was marriage to other families, which solidified his political ties.

Overpowering other tribes, such as the Tatars, he cemented his political position and expanded his empire. His military campaigns led to the conquering of far flung locations and solidified his standing. In order to achieve these victories, Genghis Khan placed competent leaders in key positions rather than family members.

Sir John Conroy (1786–1854) mistakenly thought he could become Queen Victoria’s private secretary upon her ascension. Conroy certainly had illusions of grandeur and claimed to be a descendant of Ireland’s ancient kings, but he belonged to the middle class. Conroy cozied up to the dowager Duchess of Kent, Victoria’s mother, after the Duke died in 1820. Conroy offered his services as comptroller of the household at Kensington Palace. Rumors spread that the dowager duchess and Conroy were lovers.

However, Conroy was the bane of young Queen Victoria’s life, who had to live under the super-restrictive Kensington System he helped her mother to create. Among others, the System restricted young Victoria’s interactions with the outside world; her playmates and a strict daily schedule of educational lessons were chosen for her. The goal was to make Victoria weak, compliant, and dependent on Conroy and the dowager duchess.

Conroy’s ultimate aim was to become Queen Victoria’s private secretary or have a seat on her privy council, meaning he could be close to her and possibly exert influence over her. Yet, his plans ultimately came to naught. When Victoria became queen, she banished her mother to remote quarters in Buckingham Palace and fired Conroy from his position.