Mithridates VI of Pontus: The Poison King and Rome’s Arch-Enemy

Explore the life of Mithridates VI, Pontus' ruler known for his toxicology expertise and relentless battles against Rome's expanding empire.

Explore the life of Mithridates VI, Pontus' ruler known for his toxicology expertise and relentless battles against Rome's expanding empire.

Table of Contents

ToggleToday, when people mention Alexander in a context of antiquity, they typically mean Alexander III of Macedon also known as Alexander the Great. In our collective memory, Mithridates managed to overshadow an even longer list of namesake predecessors. Mithridates VI of Pontus, who (literally) wore Alexander’s mantle, was a capable general himself, but never managed to achieve the military success of Alexander. However, what he lacked in martial prowess, he made up for in various fields, ranging from politics and linguistics to toxicology.

Had he lived in some of the previous centuries, Mithridates could have been on par with Alexander, or at least Hannibal. Nonetheless, he lived in an age when the Roman Republic was at the peak of its military might and slowly but surely expanding east. Not only was the Roman military at its zenith in the 1st century BC, but it was also led by some of its most capable commanders. However, it wasn’t all gloom for Mithridates, as these commanders were more often pitted against each other than against foreign powers, such as was his kingdom of Pontus.

The ancient region of Pontus encompassed parts of northeastern Anatolia and the southern Black Sea coast (in modern-day Turkey). It was initially a part of the Seleucid Empire, a Hellenistic successor state to Alexander the Great’s empire, in the 3rd century BC. During this time, a local leader claiming descent from Persian royalty managed to transform it into an independent kingdom through a combination of political maneuvering and military campaigns. His name was Mithridates Ktistes (c.281 – 266 BC), today known as Mithridates I, the founder of the Mithridatic dynasty.

Ariobarzanes, the son of Mithridates I, succeeded his father and expanded the kingdom’s territories further, including parts of the southern Black Sea coast. He was, in turn, succeeded by his son Mithridates II (c. 250 – 220 BC), who married Laodice, a Greek Princess of the Seleucid Empire. This connection with the old Greco-Macedonian nobility, coupled with the earlier claim to Persian royalty, would later enable his descendant, Mithridates VI, to assert himself as the protector and savior of both Persians and Greeks. Little is known about Mithridates III (c.210 – c.190 BC), however, it could have been during his reign that In December 190 BC or January 189 BC, Roman soldiers set foot in Asia for the first time. With a force numbering only 30,000, they decisively defeated a Seleucid army of 75,000. This battle, known as the Battle of Magnesia, took place near the region of Pontus and involved the Seleucids, who were neighbors of Pontus and relatives of the Mithridatic dynasty. Following this victory, the Romans forced the Seleucids to cede their territories west of the Taurus Mountains to their allies in Asia Minor, kingdoms of Pergamon and Rhodes.

It was Pharnaces (c. 185 BC – 160 BC), the fifth king of Pontus, who first came into conflict with the Romans by launching attacks on neighboring kingdoms in Asia Minor, including Pergamon, which was allied with Rome. After he lost the war against these defending kingdoms, Rome avoided military intervention. The following two kings maintained a pro-Roman policy. It was Mithridates V Euergetes, who, according to Appian, “was the first of them inscribed as a friend of the Roman people and even sent some ships and a small force of auxiliaries to aid them against the Carthaginians.” He even helped the Romans suppress an anti-Roman uprising in Pergamon, thereby assisting them in securing their first territorial possession in Asia Minor in 129 BC.

For his service to Rome, Mithridates V was awarded vast territorial possessions and allowed to expand further south unimpeded. It is uncertain whether he was aware of the threat that the growing Roman Republic and its empire posed to his kingdom. However, after he was killed in a palace conspiracy in 120 BC, Rome retook possession of Phrygia from Pontus. The stage was set for his successor’s showdown with Rome.

Historian Justin, in his History of Pompeius Trogus, claims that “in the year that Mithridates was begotten, and again when he first began to rule, comets blazed forth with such splendor that the whole sky seemed to be on fire.” Although some modern scholars were not convinced, it turned out that the same phenomenon was witnessed around September 135 BC by astronomers from the Han Dynasty in China. Similarly to the prophecy for the Star of Bethlehem, multiple prophecies at the time claimed that the comet would mark the birth of a savior that would bring about an end to an oppressive empire.

Furthermore, according to Plutarch, “when Mithridates was a baby, his cradle was struck by lightning. It burnt his clothing but left him unscathed, except for a scar on his forehead that he hid under his hair.” As incredible as these stories might sound to us, although not necessarily untrue, it is important to note that they were widely believed at the time. Consequently, they played a vital role in adding to the legend of Mithridates as a savior king.

Regardless of the spectacle surrounding his infancy, Mithridates’ rise to the throne was far from smooth. His father, Mithridates V, was poisoned in 120 BC during a banquet. It is likely that his wife, Mithridates VI’s mother, played a role in this assassination, as she took over as regent and notably favored Mithridates’ younger brother for the future kingship. Although only 12 at the time, Mithridates survived multiple assassination attempts and eventually fled into the wilderness. Modern historians speculate that he fled with a band of friends, likely those who would later become his lieutenants and confidants. Regardless, little is known precisely about his time in self-imposed exile, other than that it lasted between five and seven years.

When he was as young as 17, Mithridates returned to the capital of Sinope and, in a coup d’état, took over the throne of Pontus. He imprisoned his mother and brother, both of whom would die without ever regaining power. His ascension to kingship only made Mithridates more determined not to meet the same fate as his father, or many of his contemporaries in the treacherous courts of ancient eastern kingdoms. These fears were not unfounded because, even though he managed to recruit many allies among the Pontic nobility during his exile and purge the court of his mother’s allies afterwards, he could never be too sure about how many of his enemies still lived. One of the results of this effort is what Mithridates is still famous for today: his study of poisons.

It is suggested that Mithridates began his interest in poisons during his childhood. During his years in the wilderness, he undoubtedly learned a great deal about the poisonous plants and animals of Asia Minor. However, his serious research in toxicology would only begin after his coronation, which, like his birth, was marked by the passage of a comet.

Mithridates collected poisons and poisonous ingredients from across the ancient world. These would include poisonous plants such as deadly nightshade (belladonna), hemlock, aconite, oleander, foxglove, and ergot; venomous animals such as snakes, scorpions, and spiders; as well as mineral poisons, such arsenic, lead, and mercury salts. He would often administer these poisons to criminals sentenced to death in order to study their effects, and find potential antidotes.

Throughout his life, Mithridates would ingest sub-lethal levels of poison, including arsenic (that killed his father), in order to build up his immunity. To this day such practice of building immunity to poison is known as Mithridatism. Furthermore, it is reported by many ancient scholars that he developed a universal antidote that he ingested every day. Although this formula is lost, if it ever existed, Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History, claims that it went like this:

Take two dried walnuts, two figs, and twenty leaves of rue; pound them all together, with the addition of a grain of salt; if a person takes this mixture fasting, he will be proof against all poisons for that day. Walnut kernels, chewed by a man fasting, and applied to the wound, effect an instantaneous cure, it is said, of bites inflicted by a mad dog.

At a different spot Pliny also claims that Mithridatium, as this universal antidote is called, included blood of ducks that were continuously fed on poisonous plants. According to him, this formula, along with Mithridates’ rich medical and toxicological library, was acquired by Rome upon the death of the Pontic king, and subsequently translated into Latin.

Mithridates did not work alone, and his court, along with many artists and philosophers of the age, often attracted scientists and healers. Greek physician Crateuas the Rootcutter either worked directly under Mithridates or corresponded with him regarding his toxicological research. Conversely, in accordance with the prevailing medical customs of his time, Mithridates’ efforts to develop immunity to toxins incorporated a religious aspect. These endeavors were overseen by the Agari, a cohort of Scythian shamans who remained constantly by his side. In addition, there are also reports that during his sleep, Mithridates was guarded by a horse, a bull, and a stag, which would neigh, bellow, and bleat in response to anyone approaching the royal bed.

Nonetheless, Mithridates did not solely focus on scientific and religious matters. He significantly strengthened Pontus’ army and navy. His aspirations for expanding his kingdom faced challenges in the early years of his rule due to Rome’s presence in Asia Minor. The solution came from across the Black Sea. A long-standing Pontic ally, the Greek colony of Chersonesus in Crimea, was under constant threat from native nomadic tribes, the Sarmatians and Scythians, and sought help. The neighboring Bosporan Kingdom was in a similar position and was willing to recognize the suzerainty of Pontus in exchange for safety.

Mithridates was happy to oblige. A fleet containing a small army of 6,000 men under Diophantus arrived in Crimea, relieving the siege of Chersonesus upheld by 50,000 Sarmatians.

After receiving reinforcements, Diophantus, although similarly outnumbered, pushed the Scythians out of the Bosporan Kingdom. In the following decade, Mithridates managed to acquire nearly the entire Black Sea coast into his domain. By 100 BC, he was ruling a de facto cosmopolitan empire in which, according to ancient sources, he could communicate fluently in over 20 languages. This empire was not only rich in culture; its strategic position and control of Black Sea trade made Mithridates and his realm immensely wealthy.

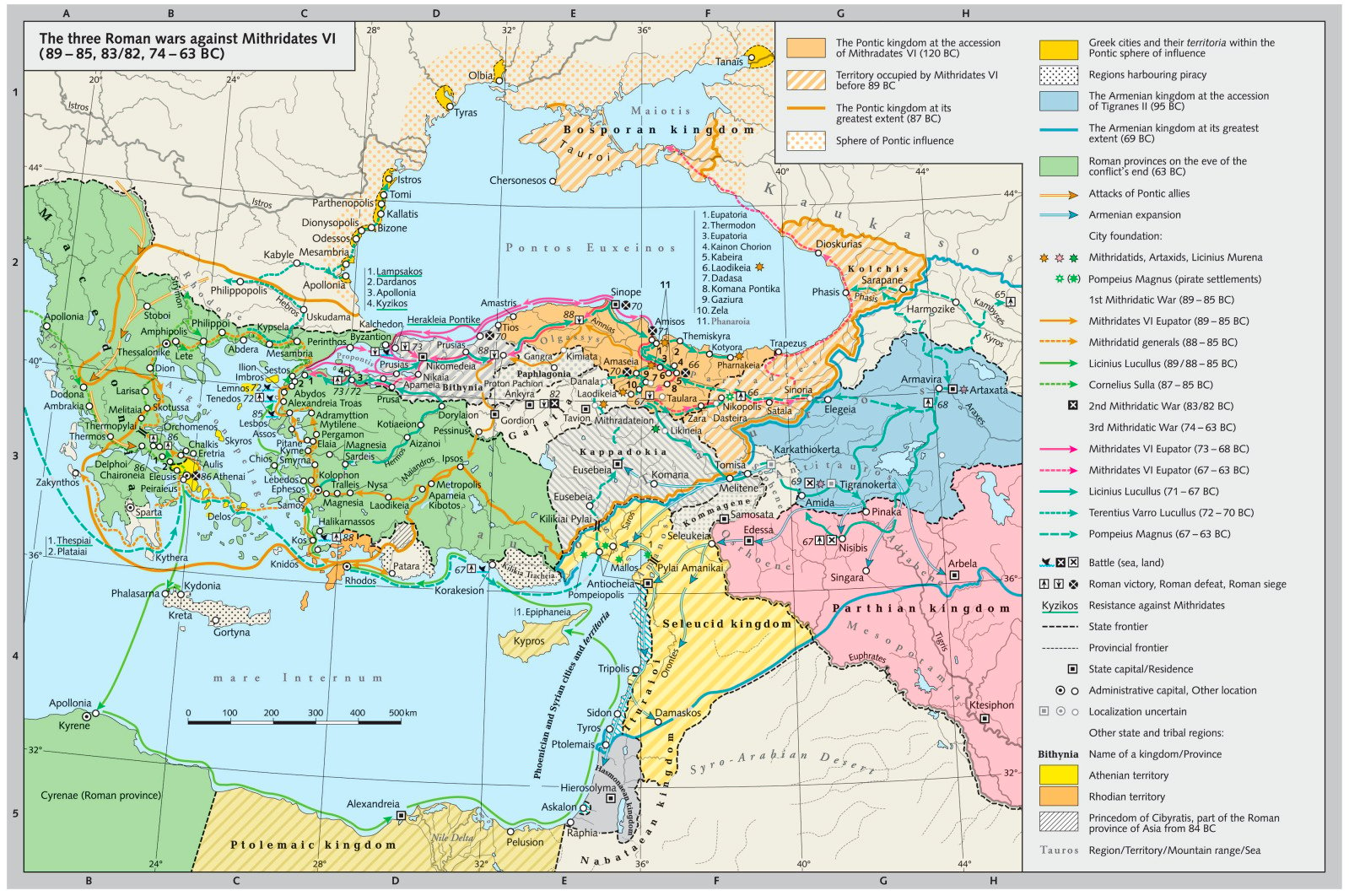

In the first decade of the first century BC, Pontus finally came into conflict with Rome. Both states wanted their allies on the throne of Cappadocia, while in Bithynia they supported two opposite sides of a dynasty civil war. Tigranes the Great, king of Armenia and son-in-law of Mithridates, conquered Cappadocia in 90 BC. With eastern borders secured, Mithridates invaded Bithynia the very same year. Nicomedes IV, the pro-Roman king of Bithynia, asked for Roman protection. Despite being busy with fighting its own allies in the Social War, Rome obliged.

Still in 90 BC, the Senate sent a diplomatic mission to Mithridates, who decided to avoid direct conflict with Rome and restore Bithynia to Nicomedes IV. Mithridates even denied aid to Italians fighting Rome in the Social War, however, this did not stop the Senate to urge Nicomedes to now raid the Kingdom of Pontus.

Doing Rome’s bidding did not pay off for Nicomedes this time. At the Battle of the River Amnias in 89 BC, Pontic troops led by two brothers Archelaus and Neoptolemus, managed to deal a devastating blow to Bithynian troops. Pontus relied on an old Persian weapon that Bithynian did not expect. Appian describes the scene:

The scythe-bearing chariots made a charge on the Bithynians, cutting some of them in two, and tearing others to pieces. The army of Nicomedes was terrified at seeing men cut in halves and still breathing, or mangled in fragments and their parts hanging on the scythes. Overcome rather by the hideousness of the spectacle than by loss of the fight, fear took possession of their ranks. While they were thus thrown into confusion, Archelaus attacked them in front, and Neoptolemus and Arcathias, who had turned about, assailed them in the rear. (…) After the greater part of his men had fallen, Nicomedes fled with the remainder into Paphlagonia.

Mithridates spared the remainder of Bithynian troops, explaining to them that their real enemy was Rome, on whose account they went into this ill-fated campaign. From this point on they chose to fight on his side. It was this enlarged army that dealt defeat to Roman consul Manius Aquillius, and his 45,000 men army, at the Battle of Protopachium. This sent a message to everyone in Asia Minor and Greece, that Rome can be beaten.

Unwilling to suffer more defeats, the Senate dispatched Lucius Cornelius Sulla, already an established general, to deal with Mithridates. However, Sulla’s old rival, Marius, decided he was the one who deserved this command, and an inter-Roman conflict ensued. Emboldened by this turn of events and determined to secure his grasp of Asia Minor, in 88 BC, Mithridates ordered all the cities to purge Romans from their midst. This genocide is known today as Asiatic Vespers and has led to 80,000-150,000 dead Latin speakers, according to ancient sources. For this show of allegiance, he granted a five-year tax-exempt status to these cities.

Mithridates was a ruthless and capable leader, but Sulla was more so on both accounts. After capturing several Aegean islands, and failing to capture Rhodes, Mithridates was invited to Athens by an anti-Roman party that held power in this famed Greek polis. Pontic troops soon poured into the Greek mainland, spreading Mithridates’ propaganda of Hellenistic revival and overthrow of Roman domination. It was at this time that Sulla had arrived heading five legions and numerous auxiliaries. Despite being outnumbered, and lacking supplies, he managed to push Pontic troops all the way to Athens.

After months under siege, starving Athens finally surrendered to Sulla but found no mercy from the Romans who pillaged the city. Pontic troops managed to escape from the peninsula and unite with the fresh new army from Pontus, led by Mithridates’ favorite general Archelaus, in Thessaly. It was here that the Pontic army encountered the best Roman general of the time in a pitched battle. As Memnon of Heraclea reports, the Pontic army outnumbered Roman at least two to one, with 60,000 against 30,000. However, a combination of Sulla’s tactics and personal bravery, superior troops, careful use of terrain, and a little bit of luck, won the day. 90 scythed chariots that wrecked so much chaos to Pontic opponents in previous battles could not be properly deployed and inflicted no damage upon their enemies.

In 85 BC, the very next year, Archelaus had the opportunity to take his revenge upon Sulla at the Battle of Orchomenus. About 80,000 Pontic troops stood across 30,000 Romans. Once again, Sulla managed to use the terrain to his advantage, preventing Archelaus from utilizing the full potential of his larger army. And once again, scythed chariots did not act the part. Chariots that did not run into Roman trap stakes and tranches turned around and ran into their own phalanx, putting the end to Mithridates’ prospects in mainland Greece.

On the other hand, Sulla had to turn his attention to Rome, and this put an end to the First Mithridatic War so hastily that a peace treaty was not even signed but instead arranged verbally. It is likely that Mithridates hoped to use his superior fleets to deal a decisive defeat to Romans. However, Romans avoided sea battles and Pontic ships primarily played a supportive role. Mithridates’ defeats in the west dealt a huge blow to his regional prestige and many cities and states under his rule rebelled. Mithridates might have underestimated Rome, but rebels underestimated him. Not only did he raise another army, he was soon once again on the path of territorial expansion.

Sulla departed Asia Minor in 85 BC, but he left behind one of his most trusted generals, Lucius Licinius Murena. Archelaus, once Mithridates’ favorite general, was afraid how his defeats in Greece would be perceived in Pontus and decided to defect to the Romans. As Mithridates was assembling armies and fleets to crush the rebellions in his realm Murena started to suspect that Romans might once again come under Pontic attack and decided to strike first in 83 BC.

While Murena was besieging Comana, a city belonging to Mithridates, the Pontic king invoked the peace deal he struck with Sulla. According to Appian, Murena responded by claiming he could not have broken the peace treaty when such a document never even existed. Mithridates sent envoys to Rome asking the Senate to enforce peace. By the time ambassadors returned, Murena managed to conquer 400 Pontic villages and towns. He even remained deaf to the Senate’s orders to cease the aggression against Pontus.

In 82 BC Mithridates had had enough. An army under his general Gordius engaged Murena in the Battle of Halys River. It seemed as if Pontic troops were about to suffer another defeat from the Romans, but Mithridates himself arrived with a fresh army. His victory over Romans had once again restored his reputation in the region. Furthermore, he wrote to Sulla asking for a peace treaty to be formalized. Thus, the Second Mithridatic War came to an end in 81 BC with the signing of the Treaty of Dardanos.

In 78 BC, Sulla died, and the balance of power started to change again. Roman general Quintus Sertorius led a major revolt against Rome in Iberia and, looking for allies, sent his envoys to Mithridates to act as advisors. Their advice would be needed when, in 74 BC, King Nicomedes IV of Bithynia died childless, bequeathing his kingdom to Rome. Unwilling to allow further strengthening of Roman presence in Asia Minor, Mithridates invaded Bithynia, starting the third and longest Mithridatic war.

The war had started well for Mithridates. Most Roman armies were in Spain fighting Sertorius, therefore his troops in Asia greatly outnumbered anything Rome managed to spare. In the Battle of Chalcedon (74 BC), Pontic troops led by Mithridates himself managed to deal a crushing defeat to Romans, both on land and sea. The Roman army led by Marcus Aurelius Cotta, consul for the year 74 BC, had more than 7,000 dead, more than 4,000 captured, as well as 60 captured and 4 burned ships. In turn, Mithridates only lost 700 men.

Following Cotta’s defeat, another consul, Lucius Licinius Lucullus, “made towards Mithridates with thirty thousand foot and two thousand five hundred horse” when, according to Plutarch, something incredible happened.

Coming in sight of his enemies, Lucullus was astonished at their numbers, and thought to forbear fighting, and wear out time. But Marius, whom Sertorius had sent out of Spain to Mithridates with forces under him, stepping out and challenging him, he prepared for battle. In the very instant before joining battle, without any perceptible alteration preceding, on a sudden the sky opened, and a large luminous body fell down in the midst between the armies, in shape like a hogshead (or wine-jar – pithos), but in color like melted silver, insomuch that both armies in alarm withdrew.

It would seem that, once again, a celestial body played a role in Mithridates’ life; however, it would be for the last time as the very next year his luck would start to change.

In 73 BC, Mithridates besieged Cyzicus, a city allied with Rome. It was during this time that Sertorius died in Hispania, and the advisors he had sent to Pontus decided to return to the favor of Rome by betraying Mithridates. Through their treachery, Lucullus managed to besiege the besiegers of Cyzicus. Trapped between two Roman forces, Pontic troops began to suffer from starvation and disease. In early 72 BC, Mithridates decided to lift the siege. While he managed to evacuate by sea, most of his half-frozen and starved troops withdrew overland, where the Romans eventually hunted down most of them.

Mithridates won and lost a few battles afterward, but he never recovered from the defeat at Cyzicus. By 71 BC, all of Anatolia was under Roman control. Mithridates’ son, ruling Crimea, betrayed his father and became a Roman client, while Mithridates himself fled to his son-in-law’s court in Armenia. Armenia was a powerful kingdom, itself wary of Roman presence in Asia Minor. However, Rome was now consolidating, and by 69 BC, they moved into Armenia meeting with one military success after another.

Even as Roman troops were marching on the Armenian capital in 76 BC, Lucullus received incredible news – Mithridates was back in Pontus. At the Battle of Zela, Triarius, who, according to both Appian and Plutarch, did not want to wait for Lucullus but instead wanted to have the glory of defeating Mithridates himself. The result was 7,000 dead Romans, including 24 tribunes and 150 centurions. Despite being almost 60 years old during this battle, Mithridates sustained a wound but kept fighting. It was his last great victory, but one worth remembering.

Lucullus planned to finish off Mithridates, but his troops, tired of constant campaigning, refused to fight. He was replaced as the commander of the east by Pompey the Great, an experienced and talented Roman general. Pompey defeated Mithridates and his outnumbered army at the Battle of the Lycus in 66 BC. With Armenia besieged by Parthia, allied to Rome, Mithridates had no choice but to flee north into the Bosporus. While Pompey was busy subduing Mithridates’ allies in Caucasian Iberia and Albania, the Pontic king managed to take revenge upon his son, Machares, in Crimea.

Incredibly, Mithridates planned to raise new armies and continue fighting Rome to the bitter end, but by this time, his subjects were tired of constant warfare and backed his younger son, Pharnaces II. Finally crushed by this betrayal, Mithridates tried to commit suicide, but no matter how much poison he took, the poison king could not die. Unwilling to fall into Roman hands, he asked one of his servants to take his life, and thus one of Rome’s most persistent enemies perished. The Third Mithridatic War had ended after a decade of constant warfare. Pharnaces II would later be defeated by none other than Julius Caesar, bringing what was left of Pontus under Roman rule.