3 Hellenistic Philosophies: Cynicism, Epicureanism, Stoicism

Three Ancient Greek philosophies to help us find inner peace in an unfulfilling material world.

Three Ancient Greek philosophies to help us find inner peace in an unfulfilling material world.

Table of Contents

ToggleIs this job all there is to my existence? Will I ever find love? Will I ever be happy? Why am I always so depressed? These sentiments might sound all too relatable for many of us. Perhaps these questions occur to us over our morning coffee, on our commute to work, or lying in bed waiting for sleep to take us. How much money have we spent in retail therapy trying to fill this nameless void in our lives? How many hours have we combed through the internet seeking answers or at least looking for distractions? And yet, no matter how often we upgrade to the hottest new smartphone or tablet, they feel quickly outdated. And however deeply we may surf the web, it seems like no one is making an app for whatever we are going through. We are frequently left to wonder, “What is missing from my life?”

If this sounds familiar, you are not alone. The everyday search for elusive fulfillment is an existential crisis experienced by many worldwide. This might seem like a modern issue, but it is actually an age-old dilemma. Many people throughout history have pondered how to lead a happy life in an unfulfilling material world. Some of the best attempts to address this dilemma come from philosophers who lived during a brief but fascinating period of antiquity known as The Hellenistic Age.

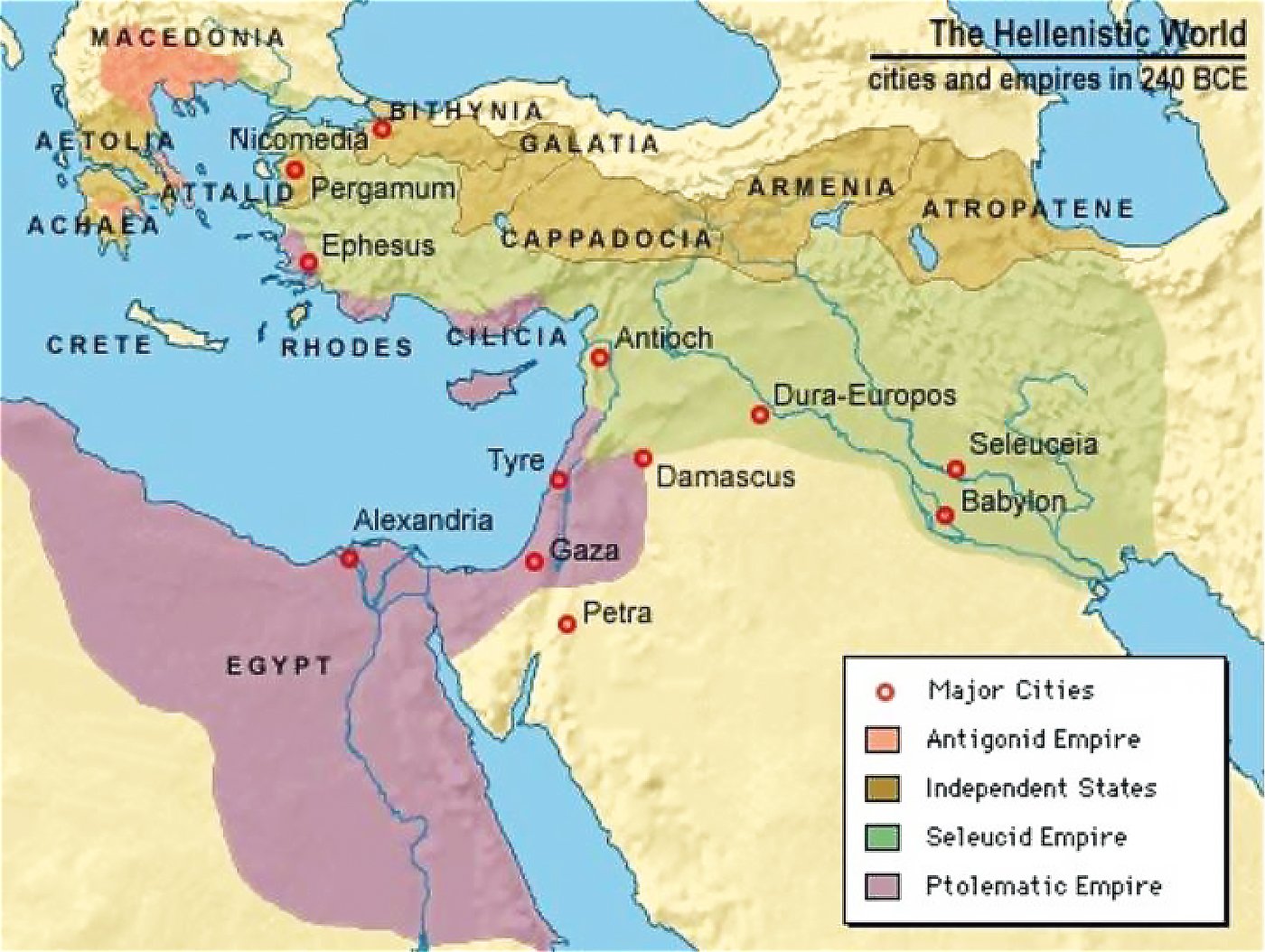

After Alexander the Great’s untimely demise in 323 BCE, his generals divided his vast empire among themselves. Egypt, the Middle East, Macedonia, and parts of Greece fell under the reign of the Ptolemaic, Seleucid, and Antigonid empires. Significant changes soon followed in all these lands. The most notable development was that Greek art and ideas were now omnipresent throughout these regions alongside the native cultures. A variation of the Greek language called Koine also became the official dialect of state and commerce. It is for this reason that the era gets the name Hellenistic, meaning “Greek-like.” However, these were not the only changes to be felt in a post-Alexander world.

During the handful of centuries between Alexander’s death and the Roman Empire’s meteoric rise, everything in the eastern Mediterranean region seemed to become larger and less personal. Local city governments were no longer the law of the land. Despotic emperors presiding in grand courts of far-off capitals now decided matters of state. Wars now took place between massive imperial armies along distant borders, not between neighboring cities. Cities themselves were also much larger in the Hellenistic Age. Sprawling urban centers such as Alexandria, Antioch, Ephesus, and Rhodes were now home to more people than ever.

This new state of affairs ushered in what some might describe as stability, and yet, for most, it brought a different kind of uncertainty. Freed from the anxieties of previous ages, people now had more time to ponder their existence, and many did not like what they found. Hellenistic people found themselves feeling isolated and alone in the great crowds shifting through the city streets. A general mood of despondency marked the era as many faced a cosmopolitan life filled with plenty of other people but little to no sense of community. As with today, people felt lost and unsure of how to fill the void in their lives.

Some people sought hope and companionship in the religious cults. Others distracted themselves with art and theater. But while the religious trends and the humanities of the age reflected the anxieties of Hellenistic life, it was Philosophy that sought to address the melancholy of daily life most directly. Three philosophical schools of thought rose to meet this widespread sense of ennui that had fallen over the Western World. Cynicism, Epicureanism, and Stoicism are unmistakable products of their time, and yet they resonate as strongly today as ever.

Today, the term “cynical” conjures an image of somebody who assumes the worst from all people and situations with sarcastic remarks for every occasion. This pessimistic stereotype is not a tremendous stretch on the ancient philosophy that bears its name. However, to be completely fair, the attitude described here better resembles toxic versions that have developed since the original idea.

Cynicism traces its origins to the teachings of Antisthenes (ca. 445 – 365 BCE), a man who was deeply versed in language, literature, and ethics, as well as a disciple of Socrates. Inspired by his iconic mentor’s temperate lifestyle, Antisthenes came to believe that genuine contentedness could only be achieved through a life of similarly extreme moderation. Such an existence, of course, was one from which most civilized people were quite far removed.

Antisthenes asserted that human discontent stemmed from our departure from our natural existence. The conveniences of civilization, meant to make our lives easier and more enjoyable, had accomplished the opposite. Life in the civilized world often leaves us unhappy and unfulfilled. We are burdened by our material possessions and fooled into lusting after the empty promises offered by the ideas of wealth, power, and prestige. True fulfillment, he argued, lay in the rejection of these societal hangups and a return to nature. Antisthenes championed a life of self-sufficiency, detached from the farcical constraints of civilized society. We would be much happier, he suggested, embracing freedom from unnatural attachments to things like owning property and maintaining a reputation. The impoverished beggar who died young could, therefore, be more content than the wealthiest executive who lived to be 100.

This ascetic lifestyle resembles the monastic practices of Buddhism and Christianity. Had it found different champions, one might speculate that it might have gone on to become something similar. Regardless, one particular beggar was soon to adopt, embody, and then add his unsavory flavor to these ideas.

Diogenes of Sinope (c. 412 or 404 – 323 B.C.), a wealthy banker’s son, was reduced to poverty and exiled from his homeland after being convicted of running a counterfeiting circuit. He made his way to Athens, where he encountered Antisthenes’ and learned of his ideas. Diogenes decided to embrace the minimalist existence envisioned by Antisthenes and live contentedly as a beggar. He made his living on the streets of Athens, taking up residence in a refuse barrel. At first, he owned nothing but a small bowl to drink from, but he eventually discarded it in favor of his cupped hands after witnessing a child drink as such. He lamented, “a child has beaten me in plainness of living.”

Diogenes became the very embodiment of Antisthenes’ philosophy but the harshest critic of Antisthenes himself. Diogenes criticized his mentor, calling him a “trumpet that hears nothing but itself.” Perhaps fueled by a desire to show up his mentor, Diogenes took Antisthenes’ ideas to extreme and even absurd lengths. Not only did he reject personal possessions and indoor living, but also basic manners, bathing, and even cooked food. He ate raw meat, openly relieved himself in the public eye, and taunted passersby with snarky comments.

This feral caricature that Diogenes made of himself led to several nicknames such as “Socrates gone mad” and, more famously, “the dog philosopher.” The latter name likely led to the term “Cynicism,” deriving from the Greek “kunikos” (“Canis” in Latin), meaning “dog-like.” Though it was initially meant as an insult, Diogenes proudly embraced the name. It was strangely fitting since, despite their dirty and uncouth behavior, dogs require very little to find joy in life. Diogenes often lauded the feral lives of animals as a model for human behavior.

Diogenes defined the Cynic lifestyle with three pillars: autarkeia (self-sufficiency), askesis (austerity), and anaideia (shamelessness). Much like Antisthenes before him, Diogenes believed that self-sufficiency and austerity freed one from the false promises of the material world. However, Diogenes went a step further and claimed that shamelessness released one from phony behavior. People learned etiquette from functioning in a civilized society, but Diogenes held that such behavior was rarely sincere. Manners, he taught, were flattery and lies people exchanged to get what they wanted from one another. Rude remarks and uncouth behavior might offend, but at least they were honest and transparent. Embracing such behavior might seem vulgar at first, but it would fade as relief set in.

As Cynicism’s second founder, Diogenes inspired a small following of imitators, including Crates of Thebes, Hipparchia, and Menippus. These later cynics built upon his model but applied a more dignified approach. The reimagined pillars of Autarkeia (self-sufficiency) and Eleuthera (freedom or liberty) joined together to carry a sense of responsibility and have replaced the more uncouth aspects of the philosophy. Austerity, once a matter of personal commitment, shifted towards valuing a modest life as a form of success. Perhaps the most significant transformation lies in replacing shamelessness with Parrhēsia (frankness), meaning to speak the truth even if it is unpleasant.

Cynicism’s core tenets, therefore, evolved over time while preserving its essence. Cynics up through the later days of the Roman Empire continued to focus on finding happiness through a life in harmony with nature based upon self-sufficiency. These Cynics also invented practices to aid in mastering one’s mentality in order to liberate oneself from the unnatural influences of wealth, fame, and power. Cynicism as a philosophy did not persist into the Middle Ages, and the term is believed to have become a pejorative sometime during the Renaissance.

Epicurean is a term most often used today to describe culinary enthusiasts. A particularly adventurous and discerning diner is often said to have an “Epicurean palette.” Such a person is open to new experiences but also knows what they like. They maintain high standards and deem life to be too short for bland cuisine. This term has fallen far from the Hellenistic tree of its origins.

Epicurean philosophy originates from its founding figure and namesake, Epicurus (341 – 270 BCE). He was a student of philosophy for the vast majority of his life and lived in several places throughout Greece, both beginning and ending his life in Athens. He began teaching when he returned to the city of his birth, where he established a school that he ran out of his own home. His preference for holding classes in his garden led to his institution being referred to simply as “The Garden.” There, he began to teach physics and ethics, which eventually culminated in his signature worldview.

Epicurus was unique among his Hellenistic contemporaries. He had no interest in politics or matters of state, which set him apart from his Stoic counterparts. He also found no kindred spirits among the Platonists because he had no use for their metaphysics. He furthermore had no use for the gods, a position that aroused suspicion among many. However, Epicurus did not dismiss the possibility of the gods’ existence. He simply found them largely unworthy of attention one way or the other.

Much of Epicurus’ worldview is rooted in his physics. Epicurus joined pre-Socratic thinkers in an ancient predecessor to atomic theory and held no belief in the concept of an eternal soul. Therefore, he believed human beings were nothing more than assemblages of matter, which simply dispensed after the body died. As far as the experience of dying was concerned, Epicurus believed that death would result in the absence of any perception. Therefore, one would not even notice that they were dead.

Such a worldview held no fear of winding up in Hades or Elysium (or perhaps heaven or hell). And if death was not a gateway to an eternal punishment or reward, then the existential dread brought on by religious dogma evaporated. The absence of the fear of death was the first step in an Epicurean existence. This psychological relief was an improvement, but it did not fix everything. Death still meant an end to one’s unique and unrepeatable life, and it could come at any moment. This being the case, Epicurus urges us to make the most of the time we have. To do this, he says, we should live a life in pursuit of what brings us true, lasting happiness.

Like Cynicism, Epicureanism seeks to maximize pleasure and minimize pain in a person’s life. However, unlike Cynicism, Epicureanism does not promote the pursuit of strictly primal or physical pleasures but rather the inner peace found in tranquility. Confusion over this important principle eventually led to a perversion of the Epicurean worldview known as Hedonism, which often promoted excess and gluttony. True Epicureanism, however, discourages excesses of such “pleasures” and sees them as problematic. They might feel good in the short term but often actually result in more pain. Epicureanism sought lasting happiness, not a quick fix.

Epicureanism encourages an emotional and mental state known as ataraxia, which is perhaps better described as an absence of pain. Once pain, fear, and suffering are eliminated, what we are left with is a blissful state of mind. Once there, one should no longer feel a need to try and balance the pains with any problematic pleasures. We will then be better able to feed our minds and fill our days with the things that bring us true fulfillment as we live “prudently, honorably, and justly.”

Epicurus saw prudence, or maintaining a low profile, as being of foremost importance. Renown and reputation inherently attracted attention, usually the bad kind. Glory, wealth, and power breed jealousy in others and usually invite their ill will. By contrast, prudence and modesty led to an inconspicuous and peaceful existence, with no one to fear. “He who desires to live tranquilly,” said Epicurus, “ought to make himself friends; Those he cannot make friends of, he should… avoid rendering enemies.”

Having a circle of good friends was the next key element. If one had people who supported them and wanted what was best for them, their lives were richer for it. It was even better if one could surround themselves with these trusted companions on a regular basis. In the company of true friends, one could truly be themselves. Moreover, with the wise counsel of good confidants, one could also hope to become their best selves. “Of all the things which wisdom provides for the happiness of the whole life, by far the most important of these is … friendship.”

Epicurus also encouraged other ingredients for tranquility, such as making time for quiet introspection in solitude. He also encouraged simple pleasures like a good book or a simple yet tasty meal. Unlike the Cynics, Epicurus saw humble enjoyment of material things as icing on the existential cake. He explicitly discouraged superstition and religion, citing their tendency to breed irrationality and fear. If anything, he thought that religious activities could be useful as a way to contemplate the nature of the gods as examples of how to lead a pleasant, tranquil existence, but nothing more.

Many took to heart what Epicurus taught them in The Garden and sought to plant gardens of their own. Throughout the Hellenistic period and into the Roman Empire, Epicureans established communities in which they could live in communal housing together. Removed from the problems of civilization, they were better able to pursue their common commitment to a life of prudence, honor, and justice. Later on, after the movement subsided, many Christian monasteries were established in housing that formerly served as Epicurean communes.

Today, someone who is described as “Stoic” could just as easily be called “the strong, silent type.” Such an individual maintains a serene demeanor, never losing their temper. They are both contemplative and steadfast, always appearing thoughtful and calm. Of all the modern denotations discussed here, “Stoic” remains the closest to its Hellenistic origins.

Perhaps the best-known of the three philosophies discussed here, Stoicism has experienced several resurgences over the centuries. It has also been refined through the thoughts and writings of several influential thinkers. Be this as it may, the virtues first articulated by its founder, Zeno of Citium (ca. 334 – 262 BCE), laid a firm foundation of guiding principles. Zeno was a wealthy merchant who turned to philosophy shortly after surviving a shipwreck. Like many Greeks, he was drawn first towards the teachings of Socrates. He was then briefly mentored by the Cynic thinker Crates of Thebes. Finding Cynicism too boorish, he went on to study in a variety of Philosophical schools throughout Greece before formulating his own worldview. Eventually, he settled in Athens to teach at his own school located in the Stoa Poikile (The Painted Porch) near the Athenian agora (town square).

Zeno’s school became known as “The Stoa,” while he and his like-minded pupils came to be referred to as “Stoics.” Like their Hellenistic counterparts, Stoics believed in returning to a lifestyle that agreed with the natural order of things. However, unlike the Cynics, they did not believe in being unkind to people. Like their Epicurean counterparts, they pursued a simple, tranquil state of mind. However, unlike their Epicurean counterparts, the core of Stoic philosophy involved metaphysical concepts. Furthermore, unlike Cynics or Epicureans, Stoics did not encourage a retreat from civilization to achieve a fulfilling life in harmony with nature. In fact, Stoicism encouraged more participation in society.

Stoics believed firmly in something known as Logos (Divine Reason), a cosmic force that gives order to the universe and everything within it. It was also believed to be the animating force in all living things, including humans. This greater cosmic understanding of human life and man’s place in the universe provided the perspective needed for Stoics to face life’s challenges as they did. “All things are parts of one single system, which is called Nature; the individual life is good when it is in harmony with Nature.”

Also, since humans were part of the living universe, all people had a spark of something divine in them. This spark manifested in people as their reason or logical mind. Therefore, one had to learn to listen to one’s own reason and do as it told them to do. The Stoics held that if people could listen to their logical minds and act accordingly, they would be in sync with nature. Living as such resulted in a state of inner peace known as eudaimonia (well-being or happiness), the highest human good. Such a state of being would further result in aretḗ (meaning “excellence,” or, in this case, “best self”). This, of course, involved ignoring more primal urges and emotional responses, which is often easier said than done.

Logic still had to triumph over the other problematic urges of being human. Emotions are a powerful force and often lead us to harm or mistreat others selfishly. Hurting another person (who had a divine speak in them as everyone did) was akin to blasphemy. Anger, jealousy, and other destructive human emotions can and must be resisted through reason. Logic taught that such emotions were petty and ultimately unworthy of governing one’s life. Furthermore, these feelings are almost always temporary and can be endured as such. In the grand scheme, these emotionally driven human impulses are just minor bumps on a much longer cosmic journey.

Of course, not everyone is a Stoic, so others would not necessarily extend the same kindness. But, again, the Stoics held that logic and reason prepare us to rise above the actions of others. We can use reason to learn empathy for others, even those who wrong us. Logical analysis can help us find compassion by seeing and understanding someone’s flawed human condition. This can lead us to forgive them for acting as they have. Forgiveness then leads to peace. This is not to say that these actions committed by the other person might not still hurt, but, again, Stoics took comfort in knowing that hurt feelings are temporary. “A bad feeling,” as Zeno once said, “is a commotion of the mind repugnant to reason, and against nature.”

In the end, say the Stoics, all pain is temporary because life is temporary. Even lifelong physical ailments will end with our death, which is not something to be feared. Like Epicurus, Zeno thought death was the end of perception and pain. However, it was not necessarily the end of everything. The Logos constantly shuffles around the same materials that made us human beings around and will again reorganize them into a different state. Therefore, death is not the end, just another change in the grand, cosmic design. “No evil is honorable” said Zeno, “but death is honorable, therefore death is not evil.”

At the end of the day, one cannot control everything that happens to them. Still, one has the power to choose how they accept their circumstances and face them with calm composure. This can be better achieved with the reassurance provided to us by logic and reason, which are themselves the cosmic spark inside us all. Zeno’s teachings laid the foundation for Stoicism by introducing the fundamental principles exemplified by the Stoic virtues of wisdom, courage, justice, and self-control.

Three philosophies, three distinct paths to happiness. All of them suggest that we pause and reconsider our estranged relationship with nature. They also suggest the key to fulfillment lies inside of us, not in what we own or what others think of us. We might purge our homes of junk, speak our minds more often, make more time for friends and simple joys, or just quit sweating the small stuff. Wherever our journey leads, we can take comfort in the knowledge that we are not alone, and we can always consult the wisdom of those who came before us.