3 Greatest Mongol Generals You’ve Never Heard Of

How these talented generals became Genghis Khan’s shock troops.

How these talented generals became Genghis Khan’s shock troops.

Table of Contents

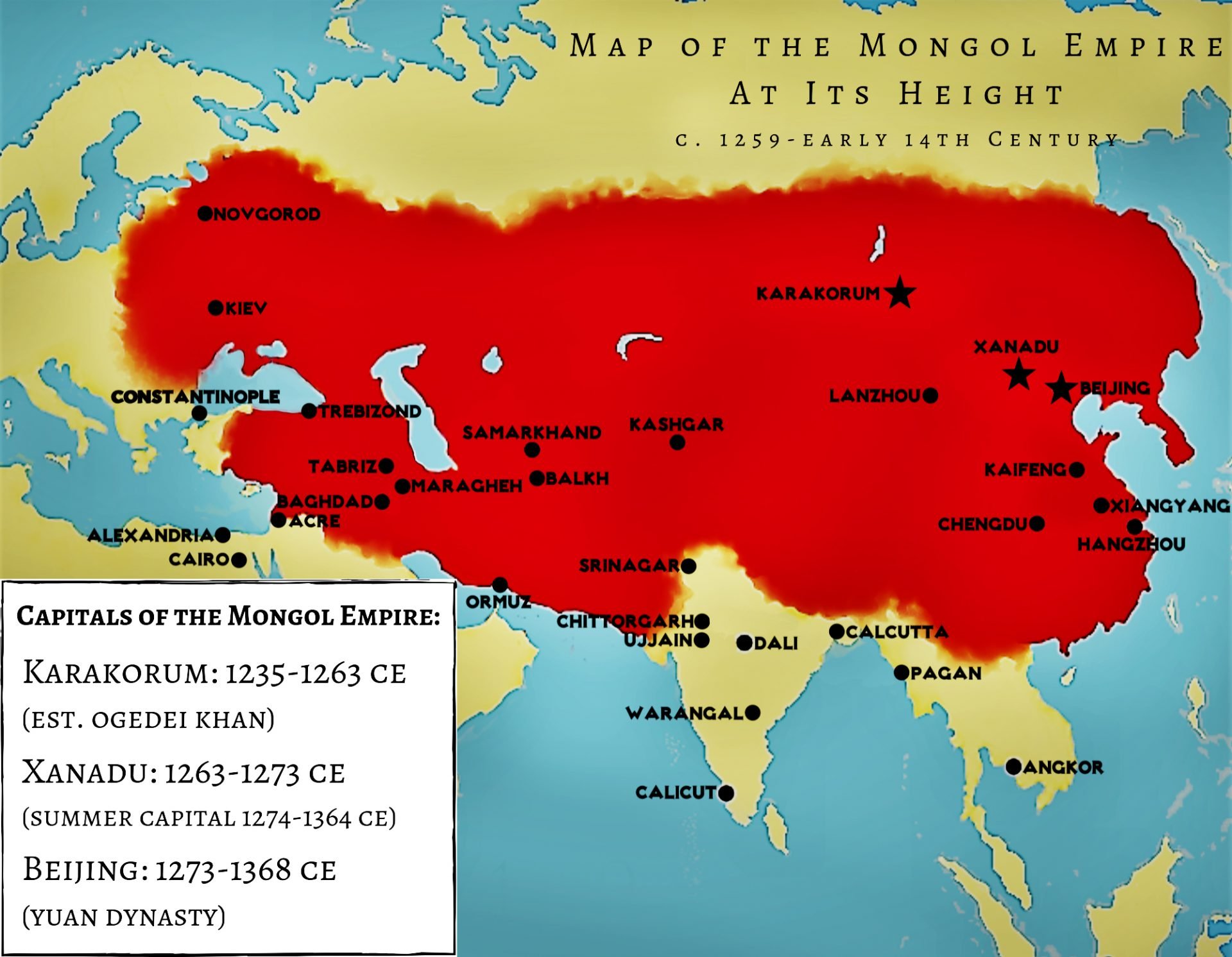

ToggleGenghis Khan created one of the most impressive empires in human history in the 13th century. As a skilled, intelligent, and surprisingly practical warlord, he rewarded those around him who showed particular talent and loyalty. It was this system of meritocracy that allowed for the Mongol Empire to grow into the largest contiguous empire in human history.

This system allowed for independent command and the use of innovative tactics to grow and govern the massive empire. While Genghis Khan receives considerable attention to this day, he was careful to cultivate shared leadership and trust those around him in their missions. It was this system that served well in cases where he would take part in person, such as in and around China, Central Asia, and Persia as well as autonomous campaigns as far away as Central Europe.

In short, Genghis Khan provided the framework that these skilled lieutenants built upon and thrived under.

In order to better understand the way that the Mongol Empire conquered most of the known world over two generations, we must first look at the system that Genghis Khan created. He was able to utilize many of the best qualities of the steppe cultures of Central and East Asia and adapt them to empire-building.

Born Temujin in the middle of the 12th century, the future Genghis Khan was the son of a minor warlord who was killed by his rivals. Temujin and his family had to survive in terrible conditions to fend for themselves. At one point he was even briefly sold into slavery.

It was here that Temujin learned the value of self-reliance through skill and loyalty. The latter was especially important, as he killed his own stepbrother for not sharing a hunting kill with his family. It was this priority for trust that superseded the traditional Mongol culture.

Over the course of the late 12th century, Temujin united the Mongol tribes, but found himself betrayed by his former blood brother who believed that the old system of passing power through heritage was more important than either loyalty or skill. It was after this moment that Temujin finished unifying the Mongols and was named sole leader by the different tribes. At this time he took the title Chinggis Khan, or “Genghis Khan,” not dissimilar to the title of Augustus in Roman history. There are several potential translations for the title that Temujin is better known as, but one that may fit the bill is ‘Universal Ruler.’

Starting from this point, the Mongol generals were able to use their years of experience hunting and fighting on the steppe to conquer much of China and Central Asia.

There were two main goals In compiling this list: to highlight leaders that are not as well-known and bring forth their interesting feats. We start with arguably the most skilled Mongol general in history, save for Genghis Khan: Subutai.

Subutai has a legitimate claim to be one of the greatest generals in history and, pound for pound, could have given Alexander the Great or Julius Caesar a run for their money.

Subutai’s family had long known Temujin’s, and according to tradition, his father aided Temujin during his difficult early years. Despite growing up from humble origins, the general was known by the Khan as a “dog of war,” along with another general: Jebe.

Jebe had been a member of a rival tribe to Temujin. During a battle, he wounded the future Genghis Khan. After Temujin won the fight, he asked the captives who hurt him. Jebe, then known as Jirqo’adai, admitted it was him and stated that should Temujim spare him he would serve as his most loyal warrior. Temujin gave him the new name “Jebe,” meaning “arrow.”

The generals were known as key innovators of Mongol warfare. They were able to use a combination of mobility and tactics to devastate enemy positions, confusing rivals into humiliating defeat. Subutai and Jebe practiced a number of traditional Mongol styles of hunting and war to perfection.

This included tactics such as the feigned, or fake retreat. In this maneuver, the Mongol army would create a “U” shape around an enemy army, making it appear that they were about to be completely surrounded. The less disciplined, often-drafted enemy forces, would break rank and attempt to escape out of the hole in the encirclement, resulting in a breakdown of their discipline.

Subutai’s forces also utilized siege machinery, which was not common among nomadic conquerors. The Mongols would often spare the educated and skilled after seizing cities, and used these experts for multiple purposes, including to build impressive siege machines. He was able to successfully use non-gunpowder artillery in battle to break up enemy formations.

Subutai’s campaigns could fill many books, so we’ll talk about some of the highlights. He was able to play a key role in the Mongol conquest of Persia. The Shah of Khwarizm had killed emissaries of Genghis Khan and the Mongols wanted revenge. In one battle, Subutai’s forces were outnumbered up to three-to-one by the Shah’s forces yet were able to escape while severely mauling the enemy army. He and fellow general Jebe led one of the most decisive lighting raids in human history, challenging and subjugating armies in the Caucasus and Europe. In the mountains between Europe and Asia, he was able to defeat the forces of the Kingdom of Georgia, forcing the country to become a vassal of the Mongols.

The two generals were also able to defeat a number of small kingdoms across what is today southern Russia before making it to the then-center of Russian culture in what is today Ukraine. Even as Russian and nomadic peoples united against the Mongols, Subutai and Jebe’s forces crushed the combined army that may have outnumbered them by as much as four-to-one. It was around this time that Jebe was killed under mysterious circumstances, likely by enemy forces.

Subutai went on to participate in the conquest of China under Genghis Khan’s son Ögedei, successfully fooling an enemy army and using siege machinery with great skill. He was able to capture a number of mountain strongholds in difficult terrain and humiliate the Song Dynasty.

Subutai’s career reached new heights with the conquest of much of Eastern and Central Europe. He returned to the region more than a decade after his initial raid. This time, his forces acted with such alacrity that the Russian princes could hardly respond.

The Mongols crushed various Russian armies and forced the surrender of the key city of Novgorod. In one battle in 1238, Subutai seized the city of Vladimir even as its Grand Duke Yuri was organizing a force against him. Yuri was informed that even as he searched for the Mongol forces, his army was already surrounded.

Subutai is perhaps best known for his invasion of Central Europe, in which his armies were able to defeat Polish and Hungarian forces in two distant battles just one day apart. Subutai would have likely continued well into central Europe, except the death of Genghis Khan’s son Ögedei meant that he had to leave Europe with his army to elect a new Khan, leaving much of the continent devastated in its wake.

Perhaps there is no figure in Middle Eastern history that strikes fear as much as Hulagu Khan. The grandson of Genghis Khan and brother of Kublai Khan, this leader conquered much of the region and left death and misery in his path.

Hulagu was the son of Genghis Khan’s last son Tolui and was said to have met his grandfather once. Hulagu was sent on a mission by his brother Möngke Khan to the Middle East to subjugate the people of the region. During his conquest, he created a massive Mongol army, perhaps the largest in their history. During his conquests, he defeated the ancient order of the Assassins, causing them to surrender without a fight.

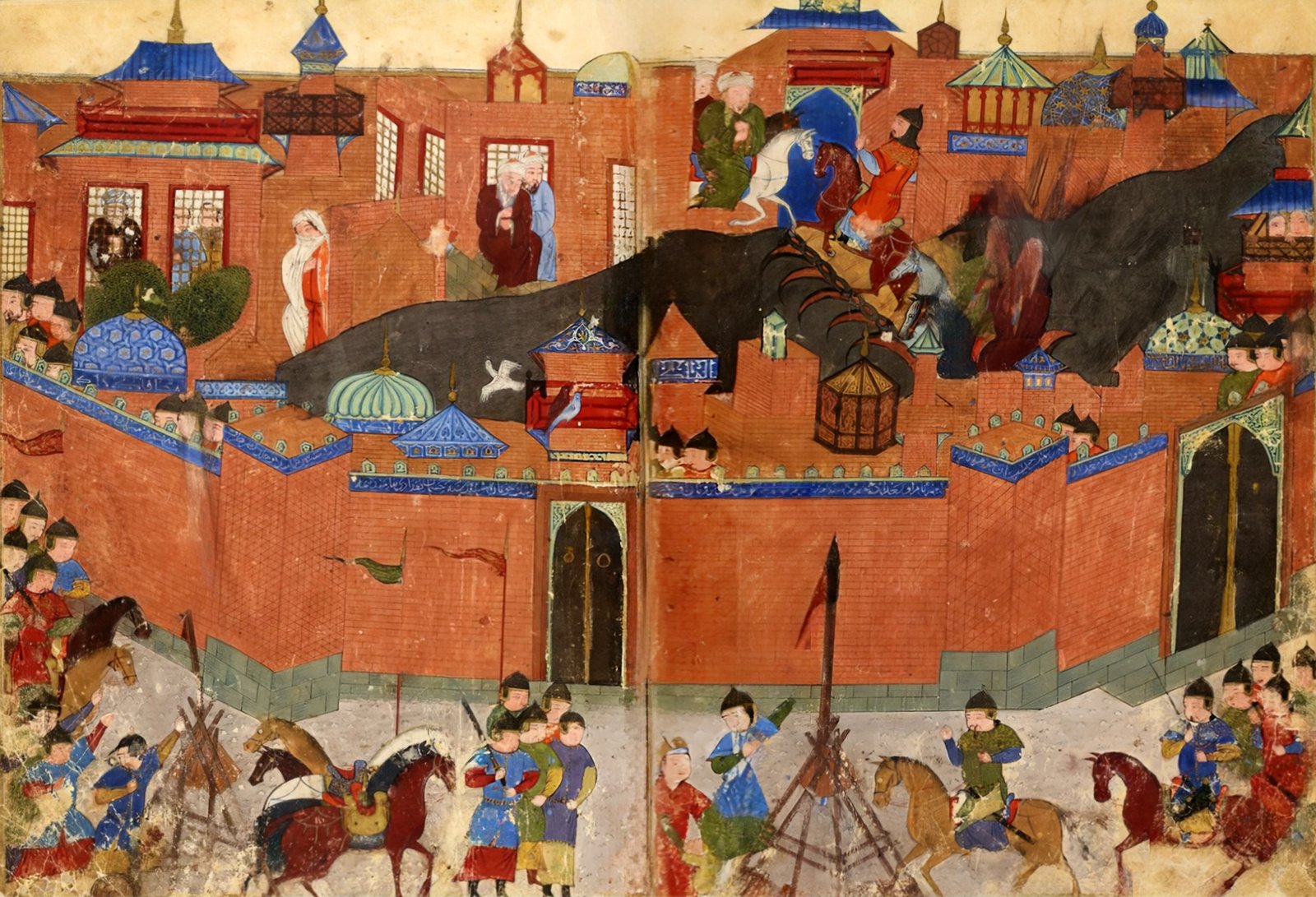

What Hulagu is known best for is the Sack of Baghdad in 1258. The city had been the center of the Muslim trade and intellectual world, during the Islamic Golden Age, and had been the seat of the head of the Islamic faith, the Caliph. Hulagu demanded that the city surrender, but its defenders believed that the previously nomadic Mongols would not be able to use siege machines. But they were very wrong. Hulagu was able to seize this city after flooding the area around the city and destroying much of the Caliph’s army. After just over two weeks, the Mongols seized the city after a short siege and laid it to waste.

Estimates of the widespread death vary, but it is often placed around a quarter of a million. Muslim historians wrote that the Tigris and the Euphrates ran red with blood and black with the ink of the destroyed Grand Library of Baghdad. The sack of the city is even written about by Marco Polo, including the death of the Caliph. There are several versions of the story, but the most likely seems to be that he was captured attempting to flee the city, was wrapped in a carpet, and stomped by horses to prevent his blood from touching the ground, a sign of respect in Mongol culture. The city was so devastated that it was nearly depopulated for centuries and its exact location was lost to history temporarily.

After taking much of the Middle East, Hulagu was forced to leave to name a new Khan, just as Subutai had been. In his absence, his army was defeated at Ain Jalut by an alliance of different Muslim forces. By the time Hulagu returned, the Mongol Empire was already beginning to fracture into different pieces and civil war.

Just about sixty years after Temujin was named the Universal Ruler, the massive Mongol Empire began to fray apart into different pieces and pages of history.