Herodotus: Was the “Father of History” a Liar?

Herodotus is credited with being the first historian but how truthful was he really in his accounts?

Herodotus is credited with being the first historian but how truthful was he really in his accounts?

Table of Contents

ToggleHerodotus has come under criticism as a propagator of lies and myths. However, is it fair to characterize him as such? He wrote what is classically considered to be the first work of history and yet there are so many errors in his work. So, was he telling the truth the way he saw it or lying to create his own legacy?

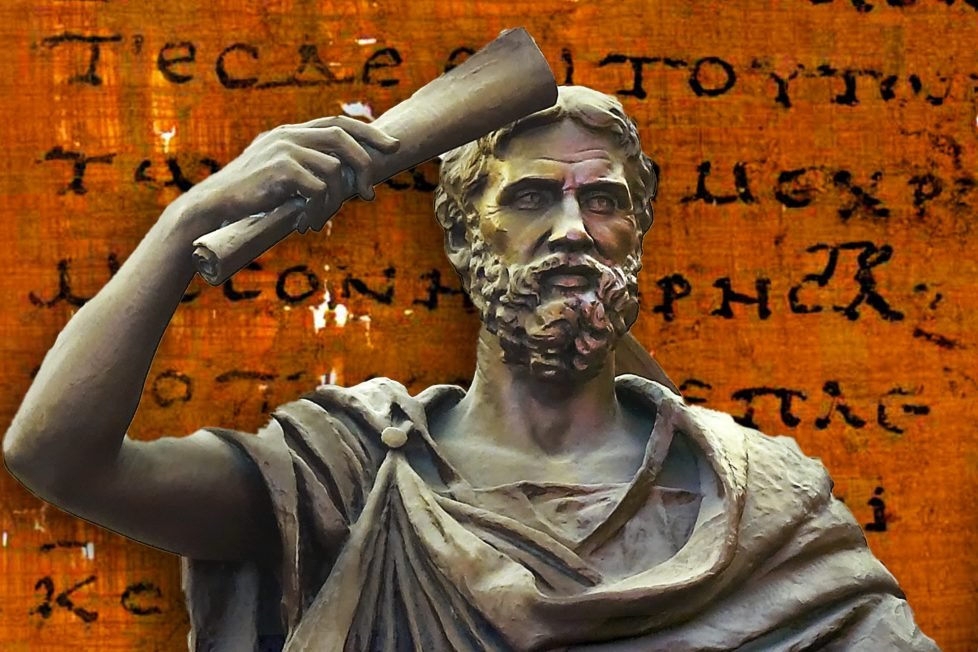

Herodotus is best known for his work “Histories,” an account of the Greco-Persian wars. He has long been called ‘the father of history.’ In fact, he was first called that in the classical period by Cicero. It is true that he is the first author of a long narrative history that still exists today. However, it may be unfair to think that Herodotus only cared about recording history. Herodotus sought to explain what was happening in the world around him. The world that he inhabited was one of war and turmoil. At the time, the great conflict between Greeks and Persians was in full swing.

Herodotus drew inspiration from Homer but instead of being driven by a Muse was pushed on by his curiosity to investigate the world and why things came to be. Herodotus traveled through Egypt, to southern Italy, and even Scythia. He was interested in the past but also the ethnography of the world. It may be that he was not only the first historian but the first anthropologist or first geographer. The most interesting thing about Herodotus is that he does not pass judgment on foreign customs. He was a proud Greek but did not necessarily find other cultures as inferior.

Of course, the characterization of Cicero that Herodotus was the father of history is shaded by the modern understanding of what a historian is — Herodotus is not that. He conveys quite openly, information that he has verified himself and information which he received from other sources. However, he also has a flair for creativity and stretches the truth quite often to make for an interesting narrative. An example of this can be seen through the detail he goes into about the battle of the Spartans at Thermopylae. The story goes that all of the Spartans died but if this was the case then where did he get his information? Additionally, it is massively unlikely that Herodotus ever visited Babylon. He never explicitly claims to have been there but suggests that he has.

One thing that we can be sure of is that not everything Herodotus wrote is true. But does that take away from his achievement of being one of the first to record an entire history of events and from being one of the greatest storytellers of the age?

As with most ancient authors, there is not much known about Herodotus’ life before his writings but there is a little information.

Herodotus was a 5th-century man from Halicarnassus. Despite his assertion of being Greek and the clear affiliation he has with the Greek nation, technically he was not from Greece. Halicarnassus, modern-day Bodrum, was in present-day Turkey. Halicarnassus was founded by people from the Peloponnese, in southern Greece, when they crossed the Aegean to the Asian side, where they came to a place called Carya. Unfortunately, there is little contemporary evidence of Herodotus’ life. The closest evidence that can be found is from the 10th century.

In the 10th century a Byzantine encyclopedia known as the Suda, which can also be translated as “the fortress,” contains mentions of Herodotus’ family. This is over a millennium after Herodotus lived but it claims that his father is called Lyxes and his uncle was called Panyassis. These names are Caryan. This implies that Herodotus was himself Greco-Caryan. He was part of the Greek world but also the Anatolian world. On top of this, Anatolia had been conquered by the Persians, so he had links to that empire as well. To be a subject of the Persian King would have opened up a world to him that stretched far to the East, to India, from the Western Edge of Anatolia. If one were to compare Herodotus to his closest rival, Thucydides who was born in Athens, then Herodotus has a greater and wider perspective on the world and his historical writing reflects this.

It is from this context that Herodotus cataloged history. Specific dates are hard to come by, but it is known that he is writing in living memory of the invasion of Greece by Persia. He spoke to people who fought in that war, which came to an end in 479 BC. It is thus accepted that he was born in and around that time.

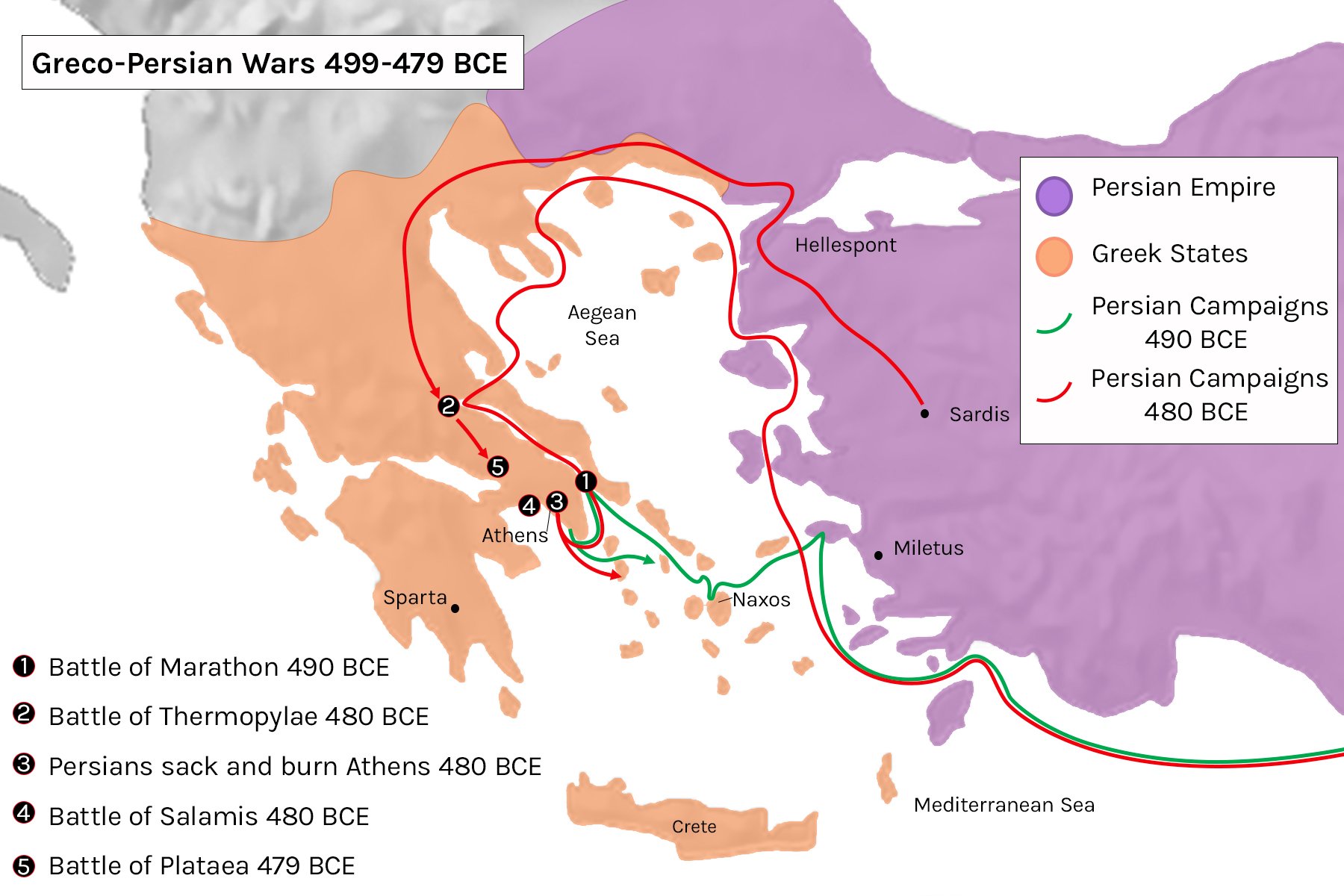

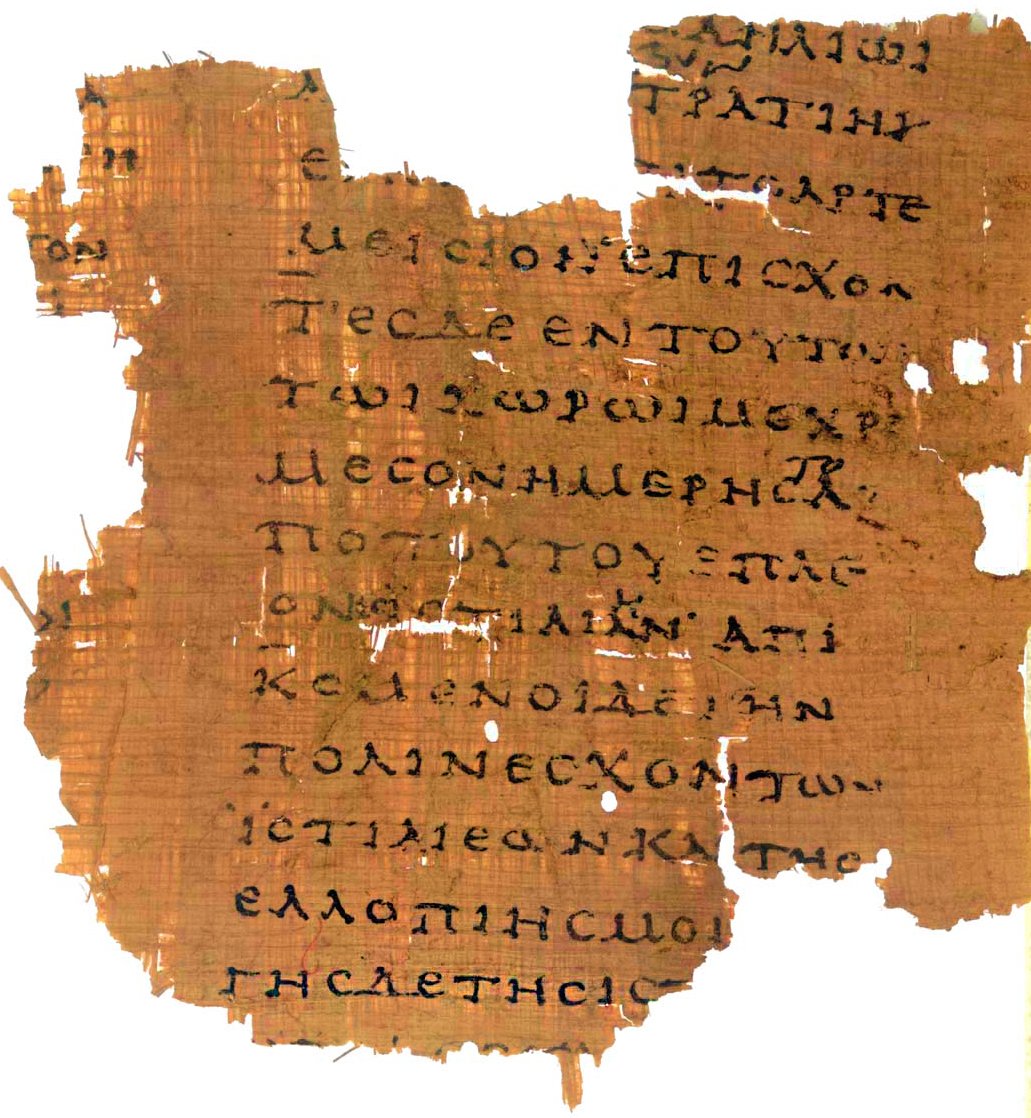

When it comes to writing “Histories,” Herodotus penned his accounts in Greek, likely intended for oral presentation. It’s believed he crafted his work for festivals where they were recited aloud, though he also preserved them on papyrus. While he may have primarily written for public readings to a local audience, there’s a suggestion that the Athenians sponsored his historical endeavors. Some stories even suggest Herodotus was exiled to an Athenian colony in his later years, making his primary audience Athenian.

Many instances in Herodotus’ writings seem contradictory at first glance. He often comes across as a relativist, someone who believes that notions of right and wrong are contingent upon the context. A prime example is the tale of the Persian King Cambyses, who successfully invaded and took over Egypt. After talking to local priests, Herodotus reports that Cambyses lost his mind, showing disrespect to the Egyptian deities and killing a sacred bull. Not merely content with documenting this event, Herodotus offers commentary, noting that people tend to view their own customs as superior, making it irrational to deride local traditions. He further illustrates this point with a story about Darius the Great, who brought together Greeks, who cremated their deceased parents, and an Indian tribe that consumed their dead. By presenting both accounts of funerary rituals, Herodotus highlights the mutual shock and indignation each group felt toward the other’s customs.

Herodotus’ style can be characterized as liminal, sitting on the boundary between two points of view. Due to his origin on the edge of two great empires, the Persian and the Greek, Herodotus can observe both sides to any given story. He is uniquely situated to be able to see how the customs of each empire would be seen as alien to one another. Thucydides, on the other hand, hailing from Athens would only be able to record the strangeness of other customs in comparison to their own, obviously correct, ones.

Herodotus was able to think himself into the shoes of every person and at least attempt to see their points of view. Herodotus, despite being heavily associated with the Greek Empire, is also massively respectful of the Persian Empire in a way that few other people of the time would have been.

Even when Herodotus discusses the outlandish behaviors of the Persian King Xerxes, he does so in a respectful manner. Xerxes attempted to build a bridge using boats across the Hellespont, lashed the sea when the weather turned against him, and generally behaved in a hubristic manner. A man who believed in his own power as being of a godly nature. Despite all of this, Herodotus speaks quite positively about him. One example is that he describes Xerxes as the most handsome and suitable man in the entire Persian army to lead this cohort into Athens.

It is not unheard of to hear people discuss history as a quest for the truth. There is no point studying it, if one cannot get to the truth of the matter. Does Herodotus provide this type of assurance? No, is the most accurate answer to this question. It is because of this fact, that Herodotus has been re-labelled in modern times from the ‘father of history’ to the ‘father of lies’.

People have argued that his writing is not of an impartial researcher following his sources as best he can, but someone who regularly embellishes the truth and outright makes up certain aspects of it. In other words, Herodotus let his imagination run wild.

The reason why this argument fails is that to an extent, Herodotus had to make up or embellish the truth where he could. He is attempting to see things from an unbiased point of view, and provide all angles for every event. The important thing to highlight is that Herodotus does not set out to write a myth. He lays out in his own prologue that he will only write events that have happened within the last 100 years of his life and will only include human events.

Despite this, he cannot be wholly sure that everything he records is correct. When he reports what other people have said, naturally Herodotus is on shaky ground. He would have spoken to many people from various places. It is unlikely that he knew every language or always understood what his sources were trying to tell him. However, Herodotus will always express doubts about the accounts that he is told. Interestingly, this can lead to significant discoveries.

For example, in one story about the Phoenicians sailing around Libya, Herodotus claims that he knows his source is wrong because the sun is said to appear on the wrong side. Whilst this may have seemed impossible to Herodotus, it reveals a fascinating detail to a modern reader that the Phoenicians did make the journey across the equator. Without necessarily meaning it, Herodotus again provides more historical facts.

Herodotus may not be the most accurate source that exists, but his work almost speaks for itself as an artistic masterpiece and remains one of the largest contemporary investigations of Greek, Egyptian, and West Asian history.