Visions of the Future from the Victorian Era

What did the future look like in an era of progress under one of history's most powerful women?

What did the future look like in an era of progress under one of history's most powerful women?

Table of Contents

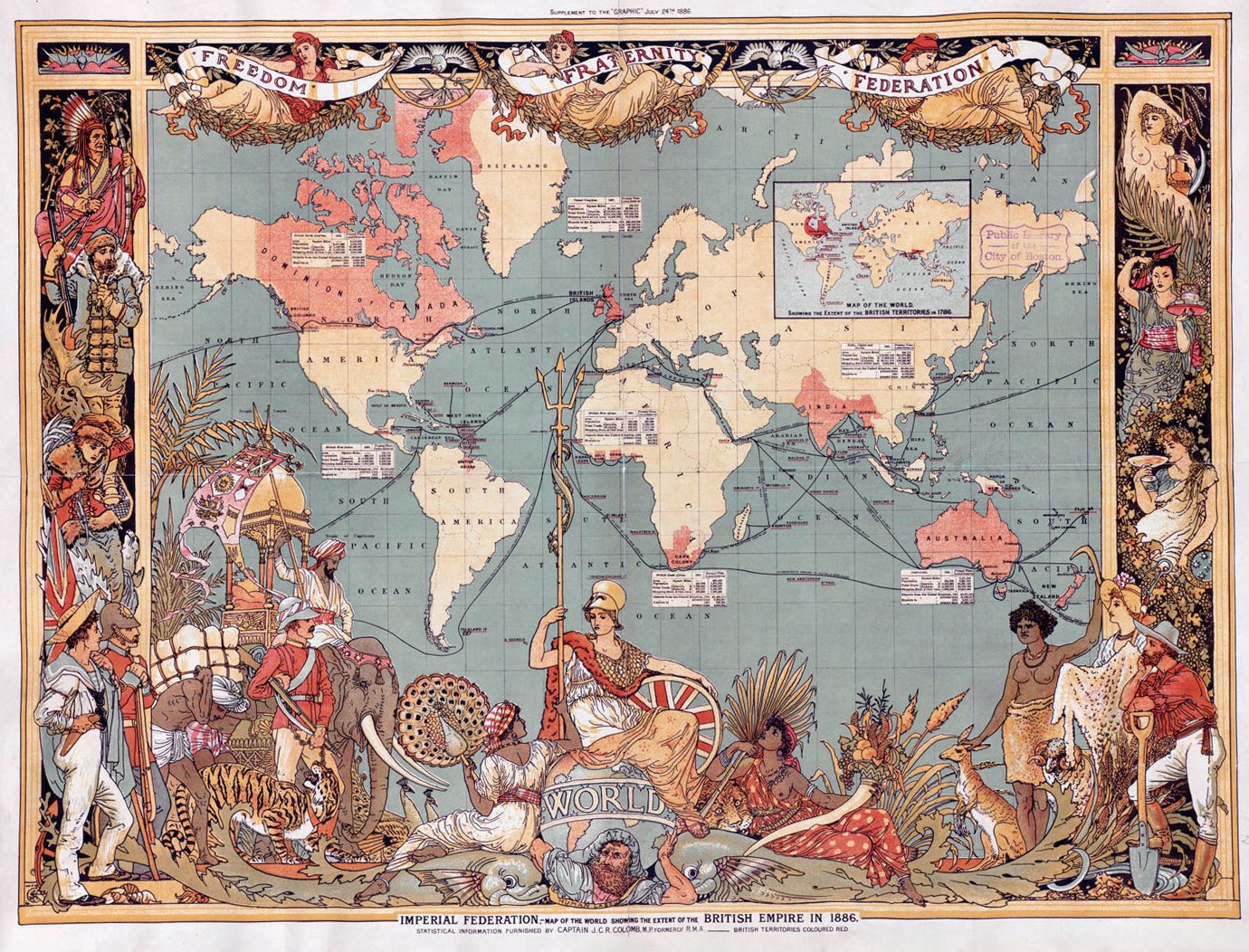

ToggleThe year 1901 marked the end of Queen Victoria’s life and the monarch’s long reign over Britain and its Empire. Over her 60 years as head of state (out-reigned only by the recently departed Queen Elizabeth II), Britain acquired an immense level of power and wealth. Through innovation in transport, political stability, communication and cultural achievements, the Victorian era was a period of progress with a profound influence on modern-day society.

When Victoria ascended to the throne in 1837, at the age of 18, she inherited a life-long appointment of monumental power and pressure. Whilst revolutions were sweeping across Europe, the British Empire was in a position of strength with a Royal Navy that had an unchallengeable superiority, playing a vital role in safeguarding trade networks and exerting the power of the Empire and its far reaches around the globe.

In Britain the first Industrial Revolution (1760 – 1840) was well underway with the world’s first modern railroad having opened in 1825. Incredible advancements in steam engines, machine powered manufacturing and large scale textile factories, made Britain a dominant force in the production of coal, iron, steel and textiles with huge economic and social consequences.

However, during this period many people were living in poverty and squalor, whilst working in horrendous conditions rife with disease, dangers and short life expectancies. The rich ruled and the poor scraped by. The social classes were very clearly defined.

Not to gloss over the period of the British Empire – a global industrial superpower that to this day was unpopular to many, especially those on the other end of the conquering, oppression and looting – but as many other empires had before, the spread of its reaches made the world a seemingly smaller place. Through travel and the trade of both goods and knowledge, this period inspired some of the world’s greatest minds and influencers of the time to radically change the world.

This era was not just impacted by the physical improvements to infrastructure with new industries, railways and factories. New ideas were spreading which changed the moral, political and social landscape. Electoral reform, public health, education and women’s rights via the Suffragettes movement were topics at the forefront of reform.

There were many breakthroughs, but to set the scene, here are some of the standout achievements.

Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace shook Victorians to their core by directly contradicting the creation story put forth in the Bible with their ideas and studies into the natural evolution of species. The publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1859 fundamentally changed humankind’s understanding of how we came to be.

Improved communication methods revolutionized trade and international relations with Queen Victoria sending the first electronic message across the Atlantic to the American President James Buchanan in 1858. By the 1870s underwater cables had been laid between Europe, America, Africa, Asia and Australia, and Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone invention also began to be installed and used towards the end of the decade.

Feats in engineering saw work begin on the transcontinental railroad installed across the United States in 1862. The year after, in 1863, the world’s first underground railway opened in London.

From 1879 – 82 Thomas Edison invented the incandescent lightbulb and lit up the United States, technology which was quickly adopted across Europe. Alongside Edison, Nikola Tesla was also harnessing the power of electricity, experimenting with power grids and a wild portfolio of other inventions.

Many of these groundbreaking Victorian era scientists and inventors relied heavily upon elaborate shows and opportunities to entice investors and attract the interests of the wealthy elites, journalists, intellects and to make a name for themselves.

No show was more elaborate than the one held in 1851, when Crystal Palace was erected in London’s Hyde Park. The giant spectacle of glass and iron, had 92,000 square meters (approx. 990,000 square feet) of floor area to host The Great Exhibition. The idea of the event was conceived by Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria and the president of the Royal Society of Arts. Their intention was to show-off Britain’s manufacturing boom on the international stage, whilst inviting exhibitors from other countries to participate in the greatest showcase of innovation and splendor the world had ever seen.

Around 14,000 exhibitors participated, coming from all corners of the globe and more than six million visitors passed through the galleries to view the latest inventions, exotic animals, luxurious fabrics, furniture, instruments, technology, art and artifacts. Items on display included false teeth, artificial legs, chewing tobacco, rubber goods, hydraulic presses, steam engines, pumps and cotton spinning machines. The exhibition was such a success that New York, Dublin, Munich and Paris quickly followed with their own grand exhibitions.

The palace was later moved to another location in London where remnants of Egyptian sphinxes are still visible today, adding to the legacy and wonder of the Victorian extravaganza.

The spread of ideas during the Victorian era also included myths, legends, fables and out-right lies for financial spin and showmanship, blurring the lines between known history, the current reality and the enticement of what may be possible in the future.

Spiritualism and séances were taken seriously by some of Europe and America’s leading thinkers of the time. During the 1850s the craze took the Victorian public by storm with shows commanding large audiences and crowds drawn to darkened venues, filled with tables occupied by groups attempting to communicate with spirits. Even Queen Victoria was said to have participated in them. The phenomenon became a focus of scientific study and attracted the likes of British surgeon William Tolmie, biologist Alfred Russel Wallace, Sherlock Holmes author Arthur Conan Doyle and French educator and author Hippolyte Léon Denizard Rivail (pen name Allan Kardec), who wrote a number of books on the subject, many of which were burnt by the church.

Amongst Britain’s most powerful traders was Frederick Horniman, a tea merchant who was also a collector of the weird and wonderful. His collection was first put on display for the general public in 1890 with a vision of giving people from all walks of life the opportunity to see and learn about global craftsmanship and creativity. He was also a prominent social reformer who campaigned for the creation of the British Welfare State, although at the same time it’s worth noting that his wealth was reliant on the exploitation of people living in the British Empire. His collection was filled with foreign instruments, African tribal masks and jewelry, artworks, fossils and exotic taxidermy creatures such as mermaids.

During this period of radical change, imaginations ran wild about what the future may look like and the direction that humankind and civilizations might take.

Held within the collections of the British Library and the British Museum are satirical prints that display visions of the future from the Victorian era. A series of prints by William Heath, entitled March of Intellect, published in the 1820’s, feature skies full of airships and flying contraptions driven by horses raised by balloons, pedal power and steam-powered vehicles, buildings can be seen in the sky with their foundations in clouds and in one, a bridge connects England to France. Another print from 1829 shows the availability of international tube travel via the ‘Grand Vacuum Tube Company: Direct to Bengal’.

French author Jules Verne, born in 1828, laid much of the foundation of modern science fiction. His first book, published in 1863, set the stage for a career as a prolific author of Voyages Extraordinaires. His books: Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1863), From the Earth to the Moon (1865), Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870) and Around the World in Eighty Days (1873), are considered masterpieces that left no stone unturned in the pursuit of adventure and discovery.

Another French novelist and illustrator of this era, Albert Robida, predicted electricity would take on a more prominent role in the future rather than steam. In his book The Twentieth Century, published in 1882, he foresaw the use of food factories, skylines strewn with cables, airships, submarine homes and food piped directly into people’s houses.

H.G. Wells took the theme of looking to the future to the extreme in his novel The Time Machine in 1895. As a British socialist and scientist he was keen to highlight concerns he had about the direction of progress, technological advances and the evolution of humankind.

Following in Robida’s footsteps, other French artists, including Jean-Marc Côté, produced a series of postcards for the 1900 World Exhibition in Paris, that envisaged the year 2000 which continued the vision of pedal powered flying contraptions and undersea colonies, along with domestic sweeping machines, and a lever-operated, mechanical barber shop that allowed one man to shave and cut multiple customers at the same time. These prints were later published in 1986 by science fiction author Isaac Asimov in the book Futuredays: A Nineteenth Century Vision of the Year 2000.

Landing back down to Earth in the 21st Century, the world has had 100 years to realize these Victorian science fiction fantasies.

One certainty is that animal rights activists are relieved that horses are not flailing around in the upper atmosphere with helium balloons attached to their hooves.

In 1903, soon after the end of Queen Victoria’s reign, aviation pioneers Orville and Wilbur Wright launched the first powered and controlled airplane flight. Only a few decades later, the 1937 Hindenburg disaster, finally killed off the idea of Zeppelins, so balloon travel never really took off in the way it was envisaged by the Victorians, instead, investors favored the development of airplanes.

Jules Verne’s vision of space travel came to fruition when the Space Race ignited in the 1950s between the United States and the Soviet Union. Both nations were in pursuit of the domination of space flight technologies. Sputnik 1, became the first Earth-orbiting satellite in history and in 1969, the US drew the ultimate ace card by landing Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the Moon. This event was closely followed by the USSR launching the first space station in 1971. Since then, incredible telescopes have been erected on earth and sent into space, probes have been sent to the Moon, Venus, Mars and beyond, and humans are now in constant orbit around Earth. The achievements have allowed mankind to view far beyond our ancestors’ ability to observe and contemplate our position in the universe.

As with the Victorian era, the wealthiest of the population often drive progress. Our modern day billionaires such as Elon Musk, Richard Branson, Jeff Bezos and Robert Bigelow are reigniting the space race with new rocket inventions, space tourism, inflatable space hotels and moon landers – blueprints that could have been pulled straight out of Verne’s stories. There are also attempts to explore the deep oceans and other realms on the precipice of our current limits of technology, engineering and understanding. As with the great entrepreneurs and inventors from 100 years ago, progress in the name of discovery, expansion and innovation has many misses before there are success stories.

Numerous other technologies have been developed that would have blown the minds of many victorians: laser beams, the internet, wireless technologies such as mobile phones, microchips, nuclear bombs and the discovery of DNA, to name a few. On a domestic level, robotic cleaners were invented and flying drones have been known to make doorstep deliveries, however, barber shops for now still rely upon one-to-one human service.

If we turn to current trends in science fiction to predict what the next century may bring, the theories don’t seem too different from some of the ideas of the Victorian science fiction visionaries: robots and AI will replace the human workforce and power every form of industry, intergalactic space travel will be available through wormholes, man will colonize planets and moons, we will have free unlimited sources of energy, microchips in our brains, time travel and total transcendence. However, the visions of our science fiction writers seem more pessimistic and dystopian than even the Victorians were.