Joan of Arc: 5 Lesser-Known Myths and Facts

Since her death in 1431, Joan of Arc has taken on a mythic stature. But what is the truth behind the legend?

Since her death in 1431, Joan of Arc has taken on a mythic stature. But what is the truth behind the legend?

Table of Contents

ToggleJoan of Arc, the peasant girl turned defender of the French nation during the Hundred Years’ War, is a historical figure around which swirls both myths and truths in equal quantities. Most individuals, and certainly history buffs, know at least the basics about Joan of Arc – she was a young lady in fifteenth century France who believed that she was called by divine voices and visions to lead France to victory over the English. Without a shred of previous military training, Joan of Arc did in fact lead the French forces to victory at the siege of Orléans and made the coronation of Charles VII a reality, but what is known to be true about this young woman? What is a myth that has been perpetuated into fact over the centuries?

As with any major historical figure, time can warp their story into a shadow of what truly happened. Politics and inaccurate retellings of Joan of Arc’s life over the years have both increased her fame but also tarnished the truth. Transcripts survive from her trials that give the reader keen insight into who this woman really was and what she believed. From her childhood to her burning at the stake, we will dive deeper into what we think we know about this French heroine and discover just what is true versus being a fabrication.

While often depicted as countercultural and “against the grain” in most instances, Joan of Arc was anything but, in her family life as a child. In fact, it is said that the worst offense she committed as a child was to sneak off to visit area churches without first seeking permission.

The testimony given at her 1456 rehabilitation (or nullification) trial by her godparents reinforces not only the solid upbringing she received from her parents but also Joan’s quiet demeanor and pious commitment to being a good Catholic. Joan of Arc’s mother, Isabelle, also gave testimony attesting to her daughter’s respect for the Church but also her compassionate nature towards those who were suffering.

It is documented, however, that Joan did have a volatile temper when it came to the conduct of her knights. Intolerant of poor behavior, not attending mass, and inappropriate language, Joan of Arc did not shy away from admonishing those she felt needed a correction.

Joan of Arc began to receive visions from God and to hear divine voices around the age of 13. These messages, which led her to help rid France from English conquest, are a topic of much debate not only in the historical community but in the medical community as well. One school of thought is that Joan suffered from a mental illness and was clearly delusional. The other is that perhaps there was more going on than originally thought.

Short of arguing the veracity of heavenly visions, which is nearly impossible to do, medical professionals have looked at the possibilities of mental illness in the form of epilepsy, schizophrenia, or even general psychosis. Analysis of her trial examinations shows a woman with a clear mind, no cognitive issues, and no signs of dementia of any kind. The hallucinations and auditory messages she experienced may give researchers cause to suspect schizophrenia, but it was clear that she did not exhibit the erratic behavior that normally accompanies it, nor did she seem to suffer from an illness as crippling as schizophrenia. In short, she would not have been able to accomplish what she had if she had a mental disorder of that kind.

The specter of epilepsy has also been raised for Joan of Arc. It has been considered that epilepsy could have caused the visions she saw, but it should be noted that she lacks all the other major symptomatic hallmarks of the disorder. If not epilepsy or schizophrenia, the two most widely considered disorders that could have plagued Joan of Arc, what else could have medically caused her visions?

The answer to that question is Bovine tuberculosis, or Mycobacterium bovis — a prevalent disease during the time of Joan of Arc. It is likely that she may have contracted the disease from drinking unpasteurized milk as a child. Bovine TB can affect the temporal lobe of the brain, thereby causing hallucinations. It can also cause the calcification of lesions in the body. This could explain why portions of her body were not wholly consumed by the first of three fires at her execution – the second two fires were employed to destroy her body entirely before casting the ashes into the river. Bovine tuberculosis may well be the medical explanation, not epilepsy or schizophrenia.

The formal charge leading to Joan of Arc’s execution was heresy. However, it’s widely contended, and in many respects confirmed, that Joan’s execution was deeply political. The English court overseeing her trial appeared less committed to uncovering the truth and more focused on the fact that Joan’s visions and messages directly challenged England. Under the pretense of safeguarding the Church and its followers from her supposed heretical deeds, a tribunal sympathetic to the English condemned her to death. They offered her a reprieve if she disavowed her visions and agreed to wear women’s attire. Initially, she complied, signing a statement to this effect, but four days later, Joan rescinded her denial. Deemed a “relapsed heretic,” she was burned at the stake in Rouen, France.

The final adjudication and sentence of death never mention a charge even resembling witchcraft. While it does refer to her as a “homicidal viper” and a “rotten member” of Christ’s body, heresy is what brought Joan of Arc to her death. To add insult to injury, Joan of Arc was also excommunicated from the Catholic Church which meant all sacraments were also withheld with the notable exception of one: reconciliation.

As a result of her tribunal and subsequent execution, we know that Joan of Arc was initially labeled a heretic by the Catholic Church. Her death was the beginning of the long road to canonization for Joan.

Approximately twenty years later, Joan’s mother and two brothers requested that the conviction be reexamined. Pope Callixtus III agreed and Inquisitor-General Jean Bréhal reopened the case. The investigation began in 1452 and by 1455 an appeal had been sent to nullify the conviction. In July of 1456, the conviction was overturned, and Joan of Arc had been cleared of heresy. No longer being a heretic, she became a martyr.

Throughout the sixteenth century, Joan’s image was most often used in conflicts that pitted the Protestants against the Catholics. In a bit of irony, especially considering how she was treated by the Church, the Catholic League carried her image in their struggles against the Protestants. Joan of Arc was widely celebrated in France and held up as a symbol of hope and piety throughout the country in the subsequent centuries.

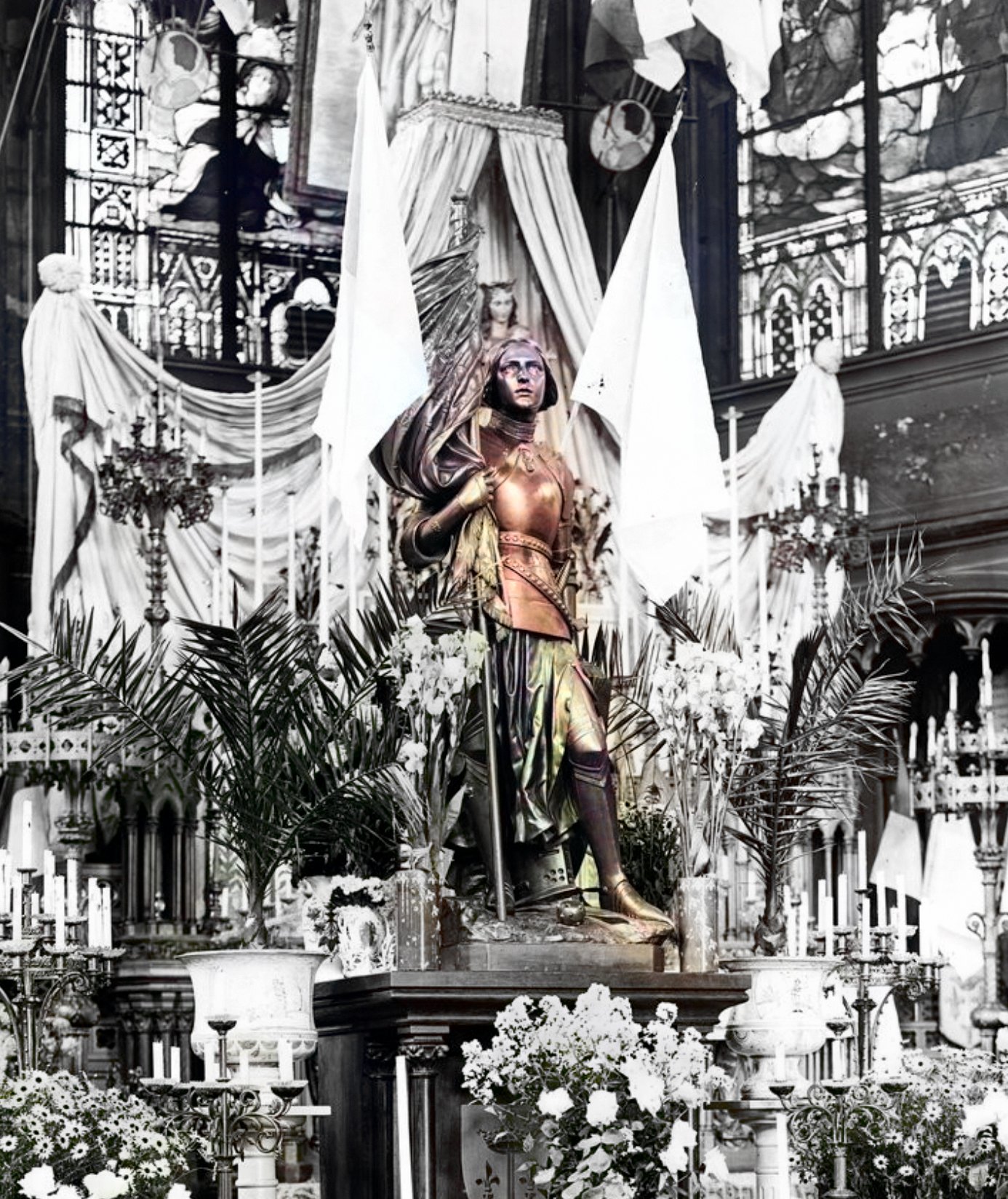

By the nineteenth century, historians had begun to publish books about Joan of Arc. This prompted the question: should the church officially canonize Joan of Arc? In 1909, Félix Dupanloup, Bishop of Orléans, led the effort that ultimately brought beatification, the first step towards becoming a saint. Her path to sainthood did hit some roadblocks when it was initially rejected because she had attacked Paris on the Virgin Mary’s birthday, along with a handful of other minor criticisms. Eventually, Joan of Arc was proclaimed venerable by Pope Pius X.

Finally, in 1920, Pope Benedict XV presided over the canonization ceremony for Joan of Arc. Held in Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome, over 30,000 people attended the occasion along with over 100 of Joan’s descendants. Ultimately, the reasons for her canonization were not for her earthly military achievements, but rather her steadfast faith and devotion to God. Joan of Arc, the young woman who had been executed by the Catholic Church for heresy, is now known as Saint Joan of Arc – patron saint of France.

Interestingly, Joan is one of only a handful of people in history to be excommunicated and later canonized by the Catholic Church.

Most paintings we see of Joan of Arc show her dressed in armor, on horseback, and waving a sword leading her forces forward. While this imagery is not wrong in some respects, the fact of the matter is that Joan never actively fought in combat.

By her own admission during her trial, Joan of Arc never killed a man in battle. This is not to say that she did not go into battle, she certainly did, but she carried her standard (flag) to avoid killing anyone in combat as well as to inspire her troops. We remember her, as she is often depicted, as a fearless warrior wading into the tide of the enemy, but the reality is that Joan of Arc brandished a banner instead of a sword when in battle.

Joan, while not actively wielding a weapon, was wounded at least twice in battle. At the siege of Orléans, Joan received an arrow to the shoulder and while attempting to take Paris the heroine was hit by a crossbow bolt in her thigh.

Like many prominent historical figures, myths inevitably surround them. This is true for Joan of Arc. Although numerous myths can already be debunked, the truth still awaits discovery. The fact remains that much about Joan of Arc remains a mystery. As historians delve deeper into the life of this French heroine, the pieces of the puzzle will come together, shedding more light on her brief yet impactful existence.

The meteoric rise, fall, and ultimate canonization of Joan of Arc is nothing short of astonishing. A young woman from a tenant farming family boldly took the leadership mantle for France at a pivotal time in their history. While she may not have won the Hundred Years’ War for France single-handedly, her examples of courage, faith, and conviction continue to be inspiring in the modern age as they were in medieval France.