The Galveston Hurricane of 1900: What Happened?

Galveston’s tragic fall in a deadly storm and Houston’s rise to economic power.

Galveston’s tragic fall in a deadly storm and Houston’s rise to economic power.

Table of Contents

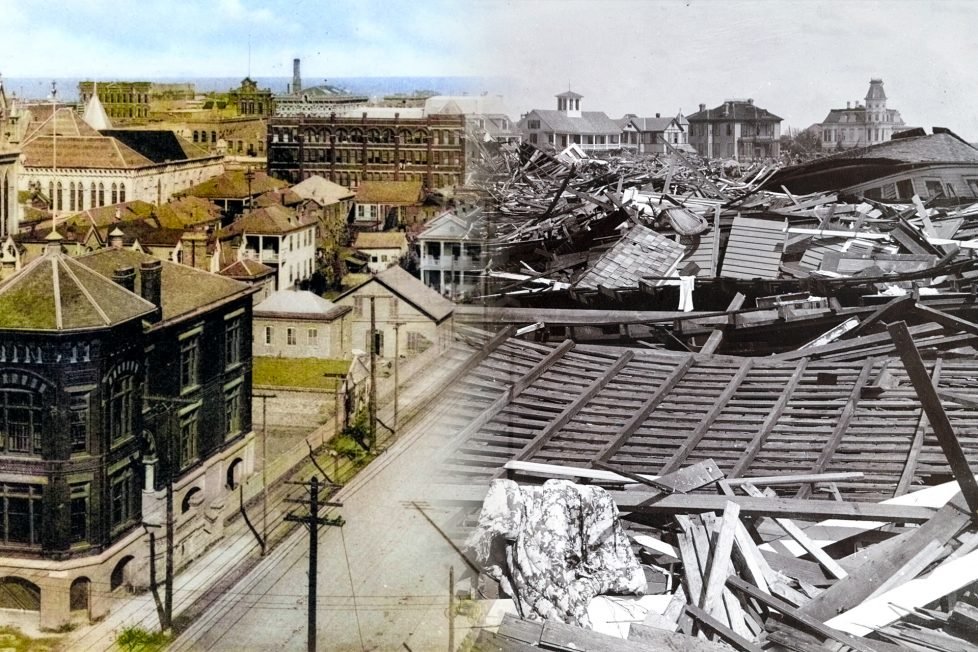

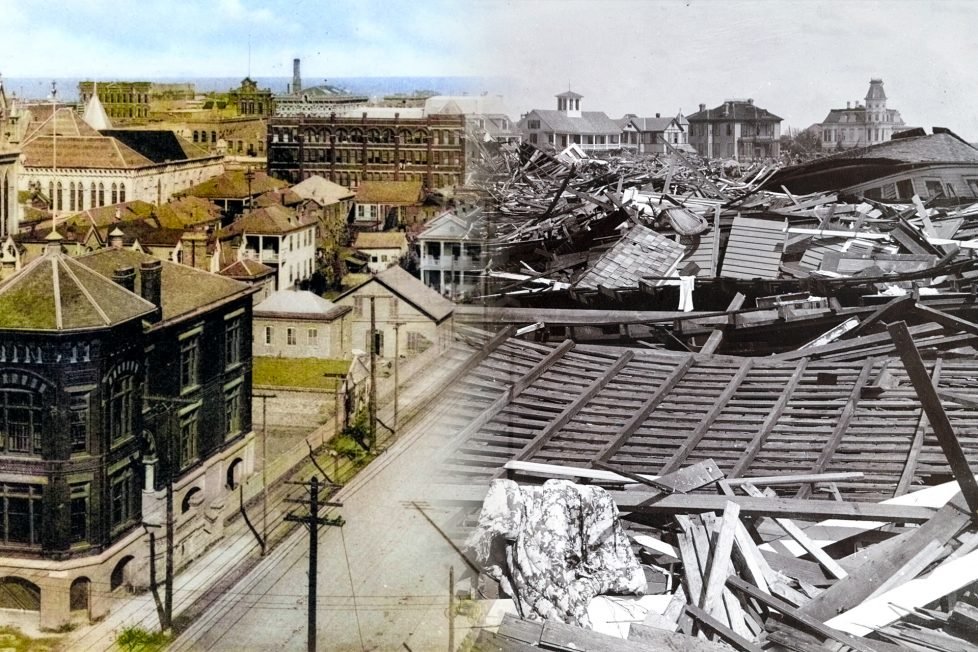

ToggleThe Galveston hurricane of 1900 is the deadliest natural disaster in U.S. history. Over 6,000 lives were lost due to the category four hurricane. The storm produced 135 miles per hour winds taking lives and demolishing more than 3,600 buildings.

At the time, Galveston was Texas’s economic powerhouse. After the hurricane of 1900, the once thriving trading hub would be left in shambles. This is a story of one port’s devastating downfall and another’s debut. The once-thriving port city’s ruin led to the economic development of Houston. If not for this hurricane, Houston might not have grown to become Texas’s largest economic port.

This article will explore how one storm did so much damage and why Galveston did not ever recover economically. We will explore exactly what went wrong, how ego cost people their lives, and the fall of Galveston’s economic reign.

Analyzing Gavleston’s history will contextualize its economic standing before the storm. In 1528, during Spain’s colonization of the New World, Cabeza de Vaca landed in the area of what historians believe was Galveston Island. The Spanish explorer and his crew famously shipwrecked miles from their intended target in Florida. He named the island “Isla de Malhado,” or Island of Misfortune. A fitting title for Galveston’s future.

Later, in 1825, the Mexican government established the area as a trading port. It was a natural choice considering the island was located between New Orleans and Vera Cruz. New Orleans was a large trading port for the Caribbean and Vera Cruz was a major port for Mexico.

When Texas became part of the United States, Galveston’s trade economy continued to develop. The port shipped cotton, sugar, molasses, pecans, and cattle. The city ranked third in U.S. cotton shipments in 1878. Additionally, Galveston was known as the “Western Ellis Island” as it was the second most used U.S. entry for European immigrants.

At the end of the 19th century, the city’s government approved and built jetties to deepen the sand bar to accommodate larger ships. In 1896, the world’s largest cargo ship at the time, measuring 21 feet, began using the port. On account of the jetties, overall imports and exports increased 37%, with 64% of Texas cotton exported through the bay.

Today, meteorologists have advanced technology to help them forecast the weather, such as satellites, weather balloons, and radar. In 1900, weather tracking technology was new and limited. It would be easy to blame a lack of knowledge and technology for the wreckage of this storm. However, this is not the case.

The hurricane first passed over Cuba. Cuban scientists predicted it was headed to the Gulf of Mexico. However, the U.S. Weather Bureau in Washington, now called the National Weather Service, incorrectly predicted the storm would pass over Florida and migrate to New England.

The U.S. Weather Bureau had only been operating for a decade and was not very advanced. The Cuban weather bureau was more advanced and had better technology. Willis Moore, director of the U.S. Weather Bureau, believed the Cuban weather technology to be inferior and shut off the communication networks between the two countries. Without the Cubans’ warning, Galveston residents were not given adequate knowledge of the severity, nor an opportunity to evacuate.

Isaac Cline was the chief meteorologist for the Galveston area. He is quoted as proclaiming that a hurricane could never demolish the bay and the idea was an “absurd delusion.” On the morning of the hurricane, Cline ignored weather signs pointing towards the nearing deadly disaster such as extremely high winds and flooding.

Moore and Cline proved to be dangerous leaders and the hurricane proved to be a lesson in leaving politics out of national safety. Additionally, U.S. weather forecasters could not give a hurricane warning without the approval of the bureau, which was difficult due to continuous poor communication.

As the storm hit the states along the gulf, the high winds took out the telegraph lines. There was no way to quickly communicate in time about the extensive damage that was coming. Florida, Mississippi, and Louisiana were also impacted by this storm, but not at the volume Galveston received.

In 1900, Galveston’s population was almost 40,000 making it the 4th largest city in Texas. After September 8th, over 20% of this population would perish in the storm.

The hurricane hit Galveston on the evening of the 8th. The surge was 15.7 feet, beating the record from 1875 which was at 8.2 feet. The surge was nearly double the highest ever recorded. Those who lived along the coast had virtually no chance of survival. Flash flooding occurred and the storm lifted and dropped entire houses, destroying them on impact.

The morning of the 9th left the survivors with extensive work to complete: searching for the missing, cleaning the debris, caring for the dead, and fixing utility services. In a hot and humid climate, disposing of bodies quickly was vital. Volunteers searched through the wreckage wearing handkerchiefs soaked in camphor and drank whiskey to dull the stench of decaying bodies.

The volume of death was so grand, that there was no space or time to bury everyone. The volunteers unearthed 70 victims a day for the first month. Many were put on cargo ships and dumped overboard. However, days later the corpses washed up on the beach. The city’s resolution was a mass fire funeral. Funerals lasted over a month as volunteers continued to find bodies during the grueling clean-up efforts. The last body was found on February 10th, 1901. Sadly, a complete death list was never made.

Prior to 1900, building a seawall had been discussed. Regrettably, the project was dismissed as the port city had survived all previous storms. The wall was seen as an expensive and unnecessary cost. The city council’s tune changed after September 8th.

In 1901, three engineers were hired to build the seawall. The plan was to build a 17-foot wall and raise the elevation of the entire city. 16 million cubic yards of sand were imported on one million dump trucks over the next decade.

The city paid for utilities and city property to be raised but individual homeowners had to pay to raise their own homes. By 1911, 500 city blocks were lifted. The elevation sloped downward at one foot every 1,500 feet toward the bay. Some areas were raised by only a few inches, while others were raised up to eleven feet.

The wall was built in sections, was over 10 miles long, and took 60 years to complete. The city paid, equivalent to today’s currency rate, $17 million per mile, totaling $177 million for the project.

Construction plans were not without issue. Due to a calculation error, the 17-foot wall was actually built to be only 15.6 feet. This was in part due to measuring during a low tide. However, the wall is still effective at stopping waves during a category three hurricane or below. Category four and five hurricanes will top the wall, but the wall still helps break the waves.

The cost and time of the renovation significantly impacted any hope for the city to rebuild to its previous economic glory. Certainty in the city’s complete revitalization continued to diminish due to the loss of population. Galveston not only lost 20% of its population to watery graves, but people also moved away in search of housing and jobs. Citizens could not wait decades for the repairs required.

Most of the port infrastructure was obliterated, including the wharves, warehouses, and company buildings. Companies could not adequately conduct business activities. The only wagon bridge to the island was swept away leaving the railroad track as the single means of transportation for the city. In total, the storm produced $30 million in damages, equal to $1 billion today. Galveston was unable to continue trade without these structures and networks in place.

Everything came to a halt until cleaning and rebuilding could begin. The port took two decades to rebound to a basic operating capacity, and even then could not achieve previous business volume. In part, companies did not want to risk investing in the area again.

Galveston city officials sought to increase tourism dollars as Houston had begun to dominate maritime trade by the time Galveston had rebuilt. Destination activities were developed to entice visitors and businesses. Electric Park opened in 1906 and hundreds of patrons visited the amusement park. Galveston’s promoted itself as the “The Coney Island of the South.” The success of this attraction led to the development of Pleasure Pier thirty years later. The pier boasted dance bands, movies, a carnival, and an aquarium. The tourist attractions revitalized commerce in Galveston.

Dominance in maritime trade shifted to Houston. Houston was further inland, less vulnerable to weather, and constructed convenient ship channels. This ultimately altered the economic landscape of the state.

Houston was established in 1836 and started as a struggling trading post in the Buffalo Bayou. The area’s economy was originally based on agriculture. The discovery of oil in Spindletop helped quickly establish Houston as a leader in oil production.

Completed in 1914, shipping channels connected Houston to the Gulf of Mexico. The channels were used to export oil, allowing Houston to become one of the top three U.S. trading ports. The city became the energy capital of Texas by the 1970s. Houston’s population boomed, causing the metro area to become the largest in Texas by 1930.

The hurricane devastation, coupled with advancements in oil and infrastructure, aided in changing the landscape of the Texas coast. Today, Houston continues to be one of the largest trade hubs and Galveston reigns as one of Texas’s top tourism destinations, both cities dominant in their own industries.