Justinian I’s Legacy and the Code of Justinian

How has a legal code from nearly 1,500 years ago shaped today's global legal landscape?

How has a legal code from nearly 1,500 years ago shaped today's global legal landscape?

Table of Contents

ToggleHuman history is replete with leaders who rule for a period and then fade into obscurity within just a few years or decades. However, a select few leaders leave legacies that endure for centuries. Exceptional acumen and skill is required to create a legacy that lasts not merely for decades or centuries, but for millennia.

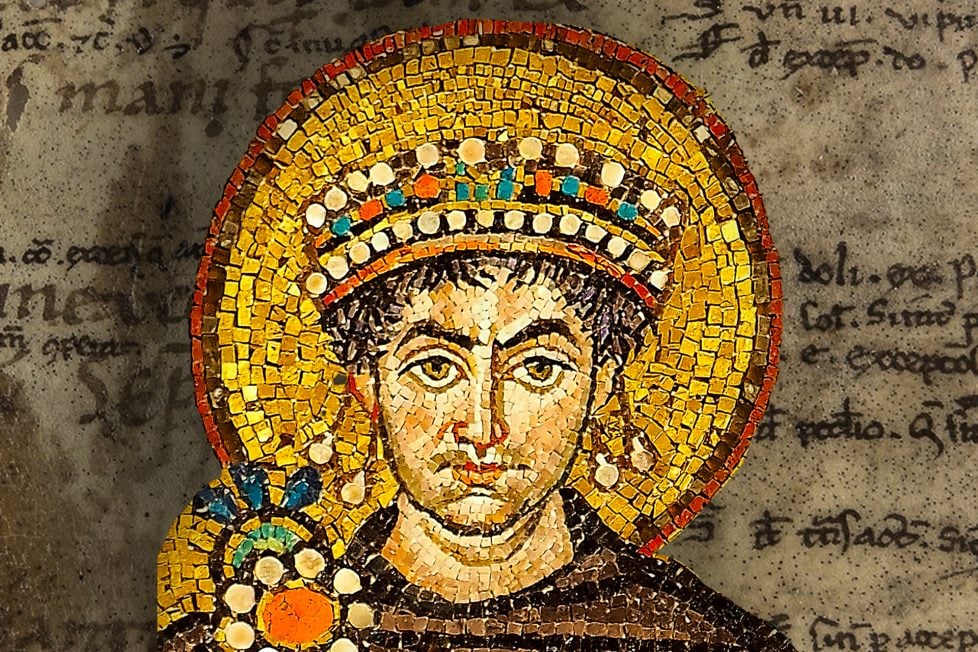

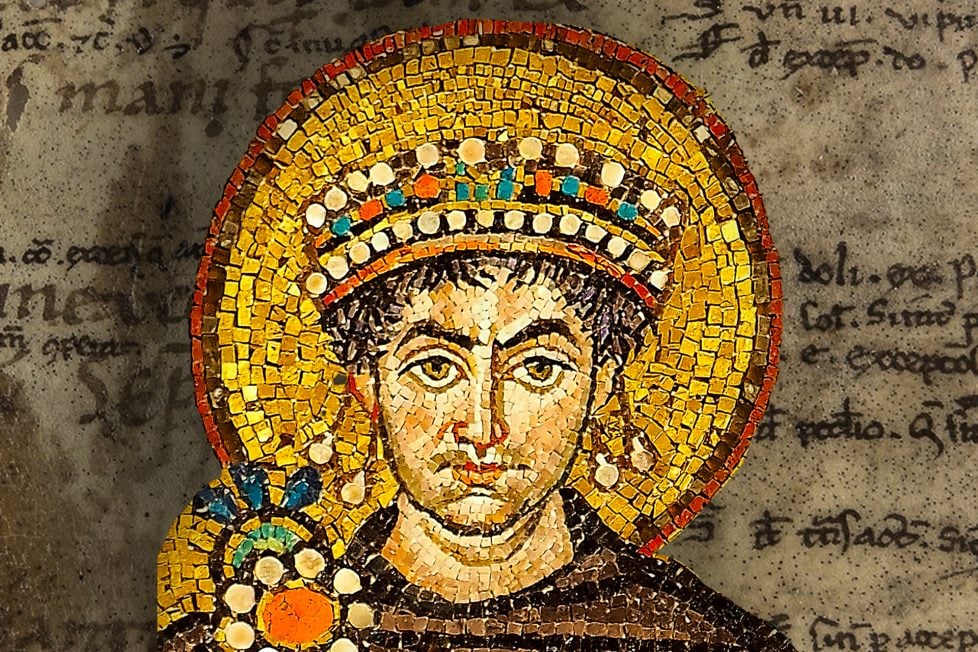

Justinian I of the Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was a leader whose legacy outlived the empire he ruled. Today, Justinian is remembered for a variety of accomplishments, such as his efforts to revitalize the once-floundering empire left in disarray following the fall of Rome. His military campaigns against the Persian Sassanid Empire in the east, as well as his judicial reforms which resulted in a comprehensive overhaul of ancient Roman laws, giving birth to the Corpus Juris Civilis.

The Corpus Juris Civilis, more commonly known as the Code of Justinian, is perhaps the most enduring of Justinian’s legacies. It has not only stood the test of time but also continues to be practiced across multiple jurisdictions. It also serves as the foundational basis of law for numerous countries spanning various continents.

The Code of Justinian isn’t the only aspect associated with him – he was also a skilled administrator, military leader, and an aficionado of art who commissioned several architectural wonders. To fully appreciate why the Code of Justinian stands as perhaps the most enduring of his legacies, it’s important to briefly explore all aspects of Justinian’s life.

Justinian was born in the year 482 AD, in Tauresium, a city that no longer exists, located 20 kilometers southeast of present-day Skopje, North Macedonia. At that time, Tauresium was part of the Roman province of Dardania. Justinian was born into a peasant family and grew up as a native speaker of Latin.

Justinian was adopted by his maternal uncle, Justin I, who ascended to the throne of the Eastern Roman Empire in 518 following a distinguished career in various Roman military units. Justinian quickly became Justin’s most trusted advisor. He was officially appointed co-emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire on April 1, 527, and took over as the sole ruler of the Empire after Justin’s death on August 1, 527.

Upon his coronation, Justinian I inherited an ongoing conflict with the Sassanid Empire in the east from his uncle, requiring his immediate attention. The Eastern Roman Empire and the Sassanids were vying for control over the eastern Georgian Kingdom of Iberia. This kingdom had been a Sassanid vassal but had recently shifted its allegiance to the Romans, largely due to religious persecution by the Persians who sought to convert the kingdom from Christianity to Zoroastrianism.

The conflict lasted several years, ultimately ending in the signing of the “Perpetual Peace” treaty in 532. While the treaty was intended to last indefinitely, peace between the Romans and Persians endured only until 540. Nonetheless, this period of tranquility gave Justinian the opportunity to concentrate on other facets of the Empire.

With his eastern frontier with the Sassanids stabilized, Justinian turned his attention to Northern Africa. This region had fallen under Vandal control following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the previous century.

The Vandals had established their capital in Carthage, extending their territory into areas of what are now Tunisia, Algeria, France, Italy, and Spain. The Vandal Kingdom also held complete control over the island of Sardinia.

Justinian’s renowned general Belisarius secured notable victories against the Vandals, which marked not only the end of the Vandal kingdom but also returned Northern Africa to Roman control. Northern Africa remained in Roman hands for more than a century, until it was overtaken by the armies of the Rashidun Caliphate in the 7th century.

After subduing the Vandals, Justinian shifted his focus to Italy, where an ongoing internal dynastic struggle presented the ideal pretext for his intervention. Once again, Justinian called on his trusted General Belisarius and put him in command of the invasion force destined for the Italian shores, aiming to restore the Empire’s former glory. This military venture served as the opening gambit in the protracted Gothic War, which went on from 535 to 554 and yielded mixed outcomes for the Roman Empire.

While Justinian succeeded in capturing a substantial portion of what is now modern-day Italy, the war came at a hefty cost and also resulted in the fragmentation of Italian territory, which wouldn’t be reunified until the 19th century. The lands reclaimed from the Goths were subsequently organized into the Exarchate of Ravenna and remained under Imperial control until 751.

Justinian’s aspiration to reclaim the territories lost by the Western Roman Empire met with only partial success. Despite his best efforts, he was unable to regain large swathes of Spain, France, and Germany, which remained under the influence and control of the Franks, Goths, and other Germanic tribes.

The dark red regions in the map above show the areas that constituted the Eastern Roman Empire when Justinian ascended to the Throne, and the lighter pink regions mark the conquests during his reign. The map below shows the total territorial extent of the Roman Empire at around 555 when it reached a peak under the long reign of Justinian.

As evidenced by the maps above, Justinian managed to recover significant areas from the Vandals and the Goths after numerous wars. His reign would mark the final attempt at bringing regions of Western Europe and North Africa under the control of the Eastern Roman Empire.

Soon after ascending to the throne, Justinian embarked on a mission to simplify the existing Roman laws, which were often convoluted and inconsistent. This effort resulted in the renowned Code of Justinian.

The Code of Justinian is not a single legal code but a compilation of three distinct legislative pieces enacted by the Emperor. Together with the Digest and the Institutes, the Code of Justinian forms the Corpus Juris Civilis. Additionally, there is a fourth component known as the Novellae Constitutiones, compiled unofficially after Justinian’s passing. However, most modern scholars include it as part of the Corpus Juris Civilis.

Justinian was keenly aware of the inefficient and slow legal process, inconsistencies among various legal codes, and complex constitutions that marked the Eastern Roman Empire when he took the throne. Just six months after his ascension in 527, he assembled a legal commission headed by his trusted jurist and advisor, Tribonian. This commission was charged with streamlining preexisting Roman laws and crafting a new code that would simplify the legal process and make it faster and more efficient for the average Roman citizen.

The newly-formed commission consisted of 10 legal scholars and 39 scribes, facing a herculean task. Their job was not only to study existing laws — some of which traced back to the time of the Roman Republic — but also to determine which should be expunged, retained, or modified before inclusion in the new code.

At the time this commission was formed, the Roman legal system principally relied on three distinct codes:

Many of the laws within these three codes were either repetitive, contradicted laws from the other codes, or had simply become irrelevant to the Roman society of Justinian’s time, as societal norms had evolved since earlier eras.

After rigorous efforts by the commission, the Code of Justinian was finalized in 529 and became effective on April 7 of the same year. The accompanying Digesta, a compendium of 50 books, served as a digest of juristic writings on Roman Law up to that point and was compiled between 530 and 533. The Institutes, designed as a textbook for law students, were also promulgated alongside the Digesta on December 30, 533.

The Code of Justinian became the governing law in the Eastern Roman Empire and laid the foundation for all subsequent legal codes until the fall of Constantinople in 1453. This ensured that regions under the jurisdiction of the Eastern Roman Empire inherited numerous laws directly from the Code of Justinian.

This impacted most of the modern nation-states that make up southern and southeastern Europe. With the loss of control over Italy in 751, the Eastern Roman Empire’s influence in Western Europe waned considerably, as the Empire would never again govern any significant territory in what is now Western Europe.

The Code of Justinian lay forgotten in the West for centuries until its rediscovery in Italy in the 11th century. From that point on, it served as the principal legal text taught and circulated at the University of Bologna, the oldest university in the Western world.

At that time, the University of Bologna attracted some of the brightest scholars, instructors, and students from all over Europe. These students carried the teachings of the Code of Justinian back with them upon completing their studies. This widespread dissemination of the legal principles outlined in the Code ensured its enduring influence and later adoption as the foundational legal framework for nearly all European nations.

Over the years, the Code of Justinian underwent numerous modifications and was translated into multiple languages, including Greek, which became the lingua franca of the Eastern Roman Empire. It also served as the foundation for several subsequent legal codes enacted by the Empire, such as the Basilika, adopted in 892 in Constantinople as an effort to translate and simplify the original Code.

The Code of Justinian is often hailed as the pinnacle of Roman legal tradition, a reputation it well deserves. It has not only withstood the test of time but has also shaped the lives of billions over the last 1500 years. Beyond influencing Roman and later Byzantine citizens, it served as the groundwork for the legal systems of various Gothic, Germanic, and Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Even countries never directly governed by the Eastern Roman Empire, such as England, Germany, Denmark, and the Nordic nations, drew extensively from the Code of Justinian. This influence extends to countries that follow the common law tradition originating in the United Kingdom, including the U.S., Canada, Australia, India, and South Africa.

Justinian was not just a capable administrator, military strategist, thinker, and builder — he was also among the few emperors of antiquity genuinely committed to improving the lives of commoners. The Code of Justinian represented an enormous effort to simplify the law, make it more accessible to the average Roman citizen, and reduce arbitrary judgments lacking any factual basis in law.

Justinian’s military gains were not long-lived, as nearly all the territories the Eastern Roman Empire acquired during his rule were lost within the next 200 years. While some architectural wonders he commissioned, like the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul and the Basilica of San Vitale, still stand today, it’s hard to argue that these structures have impacted as many lives as the Code of Justinian has.

According to some estimates, an astonishing 60.06% of the global population resides in countries where a Civil Law tradition, influenced in some form by the Code of Justinian, is practiced. It’s doubtful that many emperors can claim to have had such a profound impact on humanity more than a millennium after their passing.