The Merovingian Dynasty: Were They Actually “Weak”?

The rise and fall of one of the most fascinating royal dynasties of the middle ages.

The rise and fall of one of the most fascinating royal dynasties of the middle ages.

Table of Contents

ToggleThe Franks were members of the West Germanic group that ventured into the territories of the Roman Empire during the great migration period, often referred to as the “Barbarian Invasions.” By the mid-4th century, they had earned the right to settle on Roman land as federates. This essentially meant they had a treaty with Rome, granting them certain benefits in return for military support.

During the tenure of the Roman governor and general Aetius, the Franks aligned with Rome under the leadership of their king, Merovech. It is after him that the entire lineage of future Frankish kings is named the Merovingian dynasty. In 451, he played a role in the battle against Attila and the Huns at the Catalaunian Plains. As a consequence of this involvement, they gained possession of all of northern Gaul, extending up to the Somme River.

In the mid-6th century, the Ostrogothic state, which had once conquered Rome, fell. Subsequently, Francia became the most powerful state established on the lands of the former Western Roman Empire. Records from this early phase of Frankish history are scant. The Frankish lands were divided into regions overseen by influential and dominant local leaders, resulting in the absence of a central government. As time progressed, the successors of Merovech solidified their own position and the power of their dynasty.

Historians often focus on some of the less impactful rulers of this dynasty. But is this truly the best way to tell the story of the Merovingians? Let’s find out together.

The Merovingians rose to prominence under Childeric I (458-481), following his triumphs over the Visigoths, Saxons, and Alemanni. Unfortunately, our knowledge about him is limited. We do know he battled alongside the Roman general Aegidius against the Visigoths and aided General Paulus in combat against the Saxons.

Clovis (481-511), the son of Childeric I, stands out as the most significant ruler of the Merovingian dynasty. After his triumph over the Roman patrician Syagrius in the Battle of Soissons in 486, he consolidated most of Gaul north of the Loire. This conquest was helped by the influential Gallo-Roman clergy shifting their allegiance to the Franks. In 496, he delivered a crushing blow to the Alamanni, pushing them partially out of Gaul. They subsequently sought protection from the Ostrogothic king Theodoric. After defeating the Burgundians and the Visigoths, Clovis expanded his territory to span the entire region between the Rhine and the Pyrenees.

During these conflicts, a pivotal event in both Frankish and European history happened. Specifically, Clovis tactically addressed many of his issues with the Burgundians by marrying Clotilde, the Christian daughter of the Burgundian king. Subsequently, Clovis himself embraced Christianity. His baptism in 496 took place in the church at Reims, setting a precedent for many future French kings to be crowned there.

The significance of Clovis’s conversion is twofold: he not only became a co-religionist and guardian of the Gallo-Roman populace but also the defender of the landed aristocracy and the church. This broad acceptance solidified his position as the undisputed ruler. Before long, Clovis established Paris as the center of his reign.

Clovis’s victories, bolstered by the military aid of fellow Frankish leaders and significant war spoils, distinguished him from other kings. His embrace of Christianity further garnered the unwavering backing of the church. Eventually, through shrewd political maneuvers and cunning strategies, Clovis distanced himself from past allies, consolidating control over all the Franks.

The Eastern Roman Empire welcomed the rise of the Franks, mainly out of concern over a potential union between the Ostrogoths and Visigoths. Therefore, they acknowledged the authority of the Christian leader in Francia. They also planned on imposing their legislative and political sway over the Frankish Kingdom. Clovis largely remained indifferent to these aspirations, refraining from adopting Constantinople’s legislation. Instead, he created his own code of law, referred to as the Lex Salica or Salic Law, which held significance in Western Europe for a long period of time.

The successors of Clovis are often referred to as “weak.” But were they really?

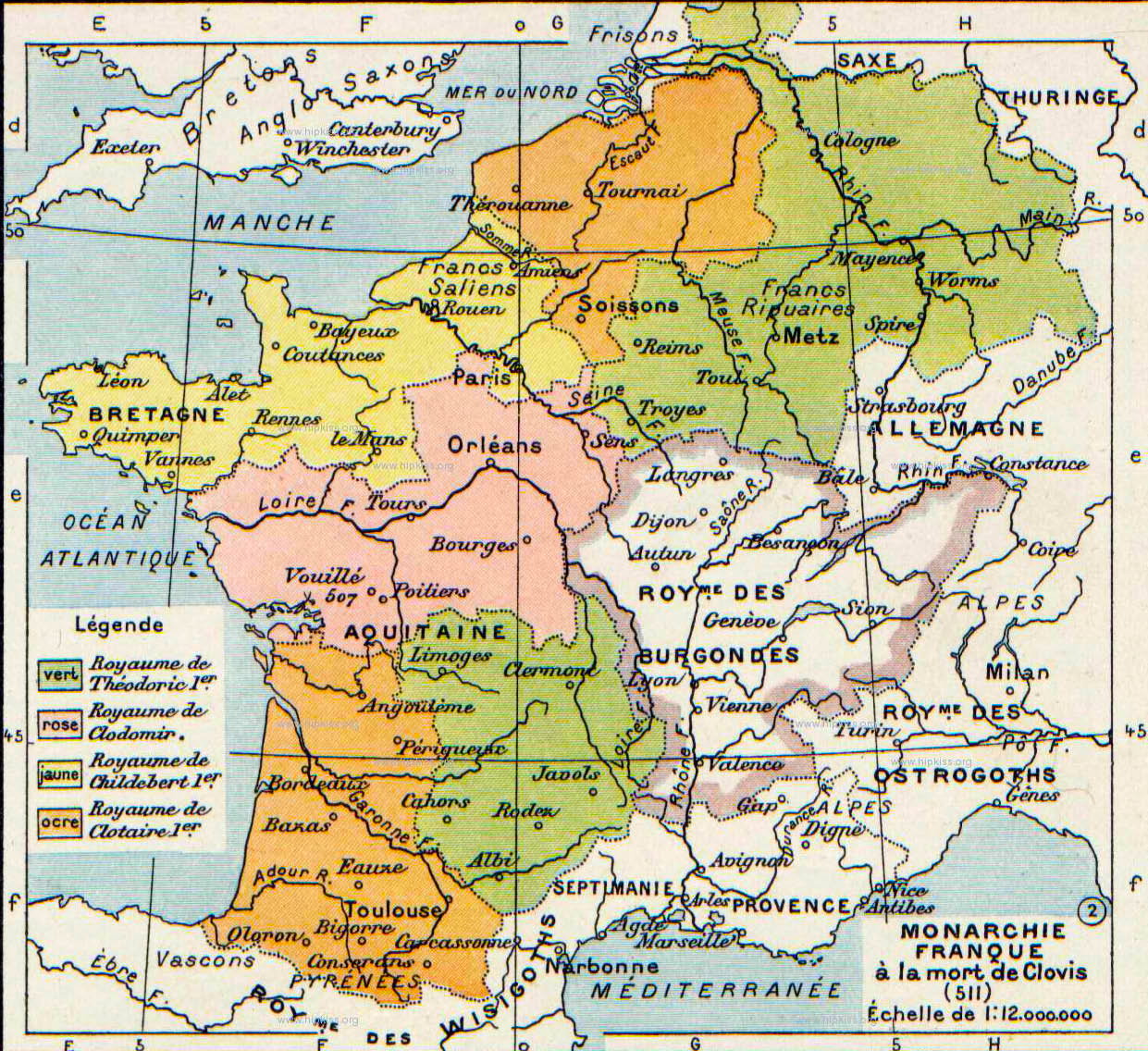

Upon Clovis’s death, the kingdom was partitioned among his four sons, in line with ancient Frankish tradition—the territories each son inherited weren’t cohesive entities. This practice persisted for roughly another century. While multiple Merovingian kings took the throne over time, the kingdom’s essence remained singular, as power was held collectively.

Theodoric became the king of Reims, Chlodomer took over Orleans, Childebert governed Paris, and Chlothar ruled Soisson. During the reigns of Clovis’ sons, they annexed Burgundy in 534. Additionally, as a reward for aiding in the conflict against the Byzantine Empire, they were granted the region of Provence by the Ostrogoths in 536.

In 539, their new king, Theudebert (534-548), ventured into Italy, challenging both the Ostrogoths and the Byzantine forces. Despite his efforts, he couldn’t firmly establish Frankish dominance there. At the same time, the Franks completed their subjugation of the Alamanni and took over Thuringia. While the Bavarians acknowledged Frankish authority, they managed to preserve a degree of their autonomy and the positions of their tribal dukes. The Saxons agreed to pay an annual tribute of 500 cows to the Frankish monarchs. Quite the achievements for so-called “weak rulers.”

The might of the Merovingian kings began to wane over time, leading to increasing fragmentation within the nation. The decline of central authority was temporarily halted under King Dagobert (629-639), referenced in historical sources as the son of Chlothar II. Ascending to the throne in 629, he reigned for just a decade—an uncharacteristically brief tenure for Merovingian monarchs. Dagobert I’s reign, spanning from 629 to 639, was characterized by his pursuit of balance and universally accepted values for the kingdom. The Byzantine emperor Heraclius also backed Dagobert, bestowing upon him the title of consul. He stands out as the last truly great Merovingian. While his immediate successors quickly veered towards decline, Dagobert’s legacy was safe. He established the foundation for the emerging French nation—a robust governance structure, a fair legal system, and a hierarchical order centered in Paris. This foundation was supported by the moral principles either instituted during his era or attributed to him posthumously.

Following the death of Dagobert, the era of the so-called “rois fainéant” (lazy kings) ensued. During this period, the true power was wielded by the majordomos, or the “Mayors of the House,” who were the managers of the king’s household, and essentially the most powerful nobles of their respective regions. Notably among these majordomos, the Carolingian family emerged, eventually founding a new royal dynasty.

During this period, three main regions within the Frankish kingdom emerged. These were Neustria, located in northwestern Gaul with Paris as its center, predominantly inhabited by the Gallo-Roman population. Austrasia, the northeastern segment of the Frankish state populated by the Eastern Franks and the Germanic tribes they oversaw. And Burgundy, a previously independent kingdom. Later, Aquitaine also gained its own independent status.

While technically the Franks were under the rule of the Merovingian monarchy, in truth, from 687 onwards, the reins of the kingdom were held by Pepin of Herstal (687-714), the majordomo and chief of Austrasia. After triumphing over the Neustrian majordomo Berchra at the Battle of Tertry in 687, he emerged as the sole majordomo of the entire kingdom. He waged successful campaigns against the Frisians, Alamanni, and Bavarians, bringing their territories under his control. In a strategic move to cement his military gains, Pepin promoted the Christianization of the Germans. He protected Catholic missionaries and used the church as a tool to increase his authority. As for the Merovingian rulers? By this time period, their influence was virtually non-existent. Regional lords began to gain independence, and following Pepin of Herstal’s demise, the nation witnessed another split.

The Frankish Kingdom’s unity was restored by the formidable majordomo, Charles (718-741), forcing all Frankish regions to acknowledge his overarching authority. Upon assuming the role of majordomo, he placed figureheads from the Merovingian dynasty on the throne. By 737, Charles felt no need to appoint a placeholder king, such was the magnitude of his influence. He embarked on multiple military campaigns, asserting Frankish dominance in Bavaria, reinforcing their rule in Alemannia, and laying waste to Frisia, where he torched pagan temples. He also subdued the Saxons once more, taking hostages and levying tributes upon them.

His crowning achievement, though, was the triumph over the Arabs (“Moors”) at the renowned Battle of Poitiers in 732. By this time, the Arabs, having overrun the Visigothic Kingdom in Spain, set their sights on southern Gaul. The Church and the Christian populace were gripped by fear, their minds filled with the sort of apocalyptic forebodings unique to the Middle Ages. Charles responded decisively, rallying the Frankish warriors. At the aforementioned Battle of Poitiers in 732, he defeated the Arabs, halting their expansion. In recognition of this victory, Charles was nicknamed “Martel” or hammer, restoring the Frankish Kingdom’s prestige. Owing to Charles Martel’s skill, the lineage of future Frankish rulers would bear the name Carolingian dynasty in his honor.

The Merovingian dynasty continued to officially be in power until the mid-8th century. It was then that Charles Martel’s son, Pepin the Short, took the crown from the last Merovingian king, Childeric III (743-751). This event marked the conclusion of the Merovingian’s three-century-long reign.