Vikings in Britain: They’ve Left Their Mark

Who were the Norse seafarers who left a lasting mark on Britain over a millennium ago?

Who were the Norse seafarers who left a lasting mark on Britain over a millennium ago?

Table of Contents

ToggleIn June 793, a few long, lean, and deadly Viking ships descended upon the monastery of Lindisfarne on the Northumbrian coast. While the people of the British Isles had seen Norse traders before, this attack was a shocking event, described thus by the chronicler Symeon of Durham:

They trod the holy things under their polluted feet, they dug down the altars, and plundered all the treasures of the church. Some of the brethren they slew, some they carried off with them in chains, … and some they drowned in the sea.

It was the start of the era of the Vikings in Britain.

While all Vikings were Norse, coming from what is now Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, not all Norsemen were Vikings. A vikingr was a man who travelled for adventure, and originally, that was who came to the British Isles, either as traders or raiders, returning to Scandinavia at the end of their voyage.

For the two centuries, any coastal settlement, or one that lay along a navigable river, was under the threat of being raided by Vikings. Abbeys and monasteries were early favorite targets of these raids, as they were less equipped to fight off attacks, and as well, tended to have rich stores of silver and other valuable items. Later, cities and towns such as Canterbury, London, and Gloucester were the targets of the raiders.

The Vikings weren’t just there for treasure; they also were slave-traders. Someone taken in a raid in Britain or Ireland could end up being sold in Byzantium, or kept as a slave in the Viking settlements in Iceland. DNA studies have shown that a majority of the Icelandic population has Scottish and Irish heredity. Women especially may have been in demand, as the pagan Norse practiced polygamy.

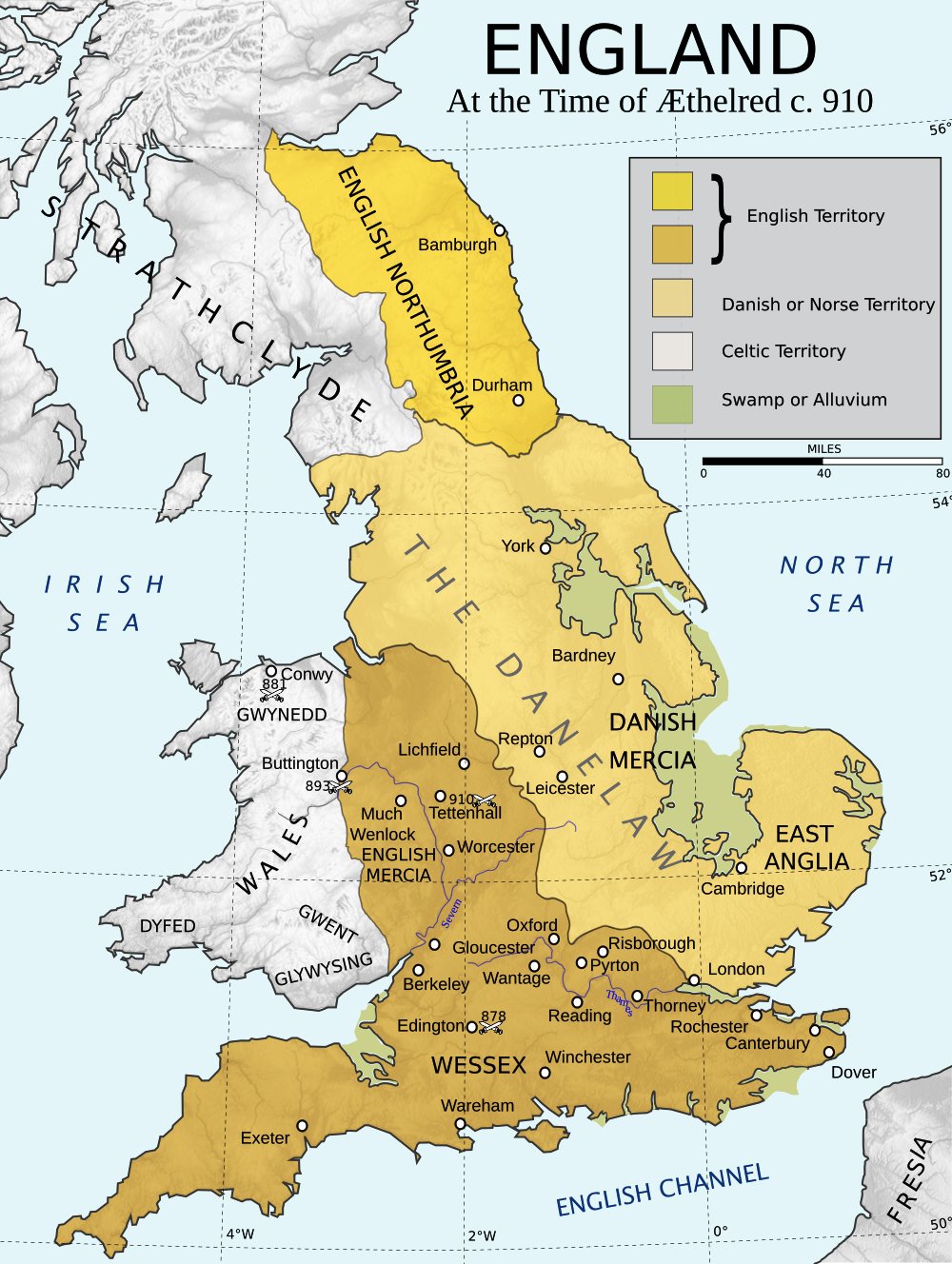

Then in 865, the Great Heathen Army landed on the shores of East Anglia, and spent the next thirteen years battling with the Anglo-Saxons with the intention of occupation and settlement. Captured by the Vikings in 867, the Northumbrian capital of Eoforwic was re-named Jorvik (now York). In 884, Alfred the Great, after defeating the Viking war leader Guthrum at Edington, negotiated the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum with the Norse that gave them control of a large swath of eastern England, from north of London to Chester, and extending as far west as Manchester. This was known as the Danelaw.

It was not until 954 that York was taken back by the West Saxons; in between, the eastern side of England was under the direct rule of the Scandinavians. The administration of law in what had previously been under Danish rule continued to follow Norse customs until the 12th century.

Meanwhile, the Isle of Man was a Viking kingdom, and Vikings first seized the Irish ecclesiastical settlement at Dublin in 841. After a decade of conflict with the Irish, Olaf the White declared himself King of Dublin in 853. Under the Vikings, Dublin became a key European slave market. The northern islands off the coast of Scotland, including Shetland, Orkney, and the Faroe Islands, saw their first Norse settlers between 800 and 850, and were ruled directly by the Norse for centuries. Here, the Vikings settled down and became farmers and fishermen rather than ruthless raiders.

Of course, England itself was ruled by Norse kings in the early years of the 11th century. Viking raids had continued throughout the 10th century, and Æthelred the Unready, the Saxon king from 978 to 1016, grew tired of paying the Danegeld, an annual bribe to the Vikings to keep them from attacking England. In 1002, he ordered the death of all Danes in England on St Brice’s Day, November 13. There is archaeological evidence that this took place; in 2008 the bodies of 35 Viking warriors who had died violently were found in a mass grave in Oxford, close to the boundary of the Danelaw.

One of the victims of the St Brice’s Day massacre was Gunhilde, the sister of Sweyn Forkbeard, the pagan king of Denmark. His response was a decade of concerted attacks on England. By 1013 he had succeeded in sending Æthelred into exile, along with his wife and children, but Sweyn died only five weeks after claiming the throne on Christmas Day 1013. He named his son Cnut (also known as Canute) to succeed him, but Æthelred returned with an army and regained the throne.

Cnut returned to fight in 1016, and Æthelred, suffering from an unspecified illness, died on April 23. At the Battle of Assandun in October, Cnut decisively defeated Æthelred’s son and heir Edmund. He reached an agreement that gave him control of most of England, while Edmund kept the traditional Saxon kingdom of Wessex. Whoever outlived the other would gain control of the whole kingdom. Edmund conveniently died on November 30, and Cnut became the king of all England, holding his coronation in December.

Cnut ruled until his death in 1035, with a kingdom that encompassed England, Denmark, Norway, and part of Sweden. He converted to Christianity and married Cnut’s widow, Emma of Normandy.

Cnut had named his son by Emma, Harthacnut, as his heir. However, the new king was fighting Norwegians back in Denmark, so his older brother, Harold, took control in his absence. Harold Harefoot was the son of Ælfgifu, who was either Cnut’s first wife or mistress. Because he was not a Christian, the Archbishop of Canterbury refused to let him be crowned with the royal regalia. Harold died in 1040, at the age of only 24.

Harthacnut then took the throne that his father had left him, receiving a full coronation at Westminster Abbey. However, he rapidly became an extremely unpopular king. One of his first actions was to have his brother Harold’s body dug up, beheaded, and thrown into a fen. He had the city of Worcester burned to the ground when two of his tax collectors were killed there.

Luckily for England, his reign, though nasty and brutish, was short. Possibly suffering from tuberculosis, he died in 1042 after a bout of heavy drinking. The year before he had named Æthelred’s son Edward as his heir, and so after his death a Saxon king once again sat upon the throne of England, but not for long.

In 911, the Viking ships of Rollo, a Viking warlord from either Denmark or Norway, had sailed up the Seine and laid siege to Paris and Chartres. Although Rollo was not successful, King Charles the Simple of France gave Rollo the northwest corner of France to defend against further Viking invasion, and so his descendants ruled Normandy as dukes.

A century and a half later, Rollo’s great-great-great grandson William the Bastard, the Duke of Normandy, invaded England and seized the throne, ruling as William I, commonly known as William the Conqueror. His descendants still sit on the British throne today, so in a sense, Britain is still ruled by the Vikings.

Depending on what part of Britain you visit, the traces of the Vikings can still be seen today. Certainly in the former Danelaw, along the east coast and reaching inland to the Midlands, many place names hearken back to the Viking occupation. For instance, the suffix “thorpe” in a place name, such as Scunthorpe, is a Norse word meaning village or farmstead. Another suffix, “by”, means farm. There are hundreds of villages, towns, and cities with those endings in what used to be the Danelaw.

Today, some days of the week are still derived from the names of Norse gods. For instance, “Wednesday” is “Woden’s Day”, Thursday means “Thor’s Day”, and “Friday” is named after the Norse goddesses Frigg and Freya.

The English language in general also owes much to the Viking occupation. Among many others, the words “anger”, “egg” and “mistake” are of Norse origin. On the island of Orkney, there’s quite a bit of the old Norse language, known as “Norn”, surviving today as part of the local dialect. And Shetland’s motto is in old Norse: með lögum skal land byggia (with law shall land be built).

Most significantly, however, part of the population of the British Isles can trace their ancestry back to the Vikings. There is some disagreement about how prevalent Norse ancestry is. Earlier studies seemed to indicate that Shetland, which remained under the direct rule of the Danes until 1469, had as high as 60% of the population with Scandinavian DNA. However, more recent studies have drastically reduced that number. The highest percentage is on the island of Yell, where 24% of the inhabitants have Scandinavian DNA. Overall, it appears that 6% of the British people have Viking DNA. Considering that in Sweden, one of the Viking homelands, only 10% have Viking ancestry, that’s a fairly high number.

There is actually remarkably little physical evidence of Viking settlements in Britain, but significant archeological digs in Repton in Derbyshire have uncovered Viking graves from the time of the Great Heathen Army, showing that they landed with probably 5,000 warriors, with their own horses.

Britain has of course been invaded many times over the millennia, but the story of the Vikings has caught the popular imagination, and its influence has continued into the present day.