Thrace: The Birthplace of Spartacus and the Realm of Ares

The story of ancient Thrace, from the Heroic Age to the arrival of Rome.

The story of ancient Thrace, from the Heroic Age to the arrival of Rome.

Table of Contents

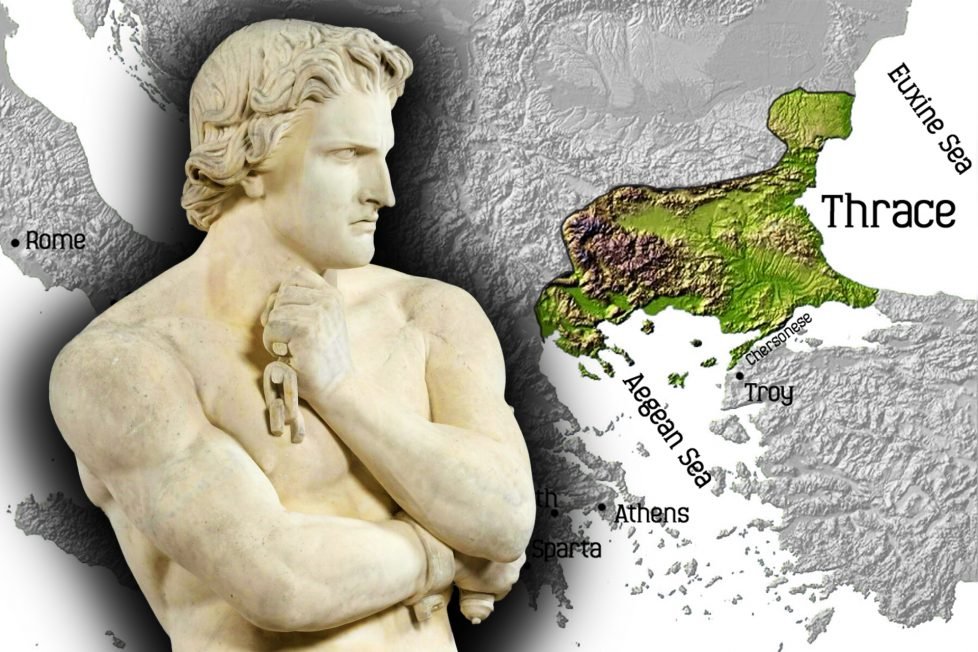

ToggleAt the time when the most famous Thracian in the world was a runaway slave named Spartacus, who led a revolt in 73 BC, it was hard to imagine that there was a time when Thrace (Thracia) was more prominent than Rome. Yet, some three and a half centuries earlier, Herodotus wrote that “the Thracians are the most powerful people in the world, except, of course, the Indians; and if they had one leader or were in agreement among themselves, it is my belief that no match for them could be found anywhere, and that they would far surpass all other nations.”

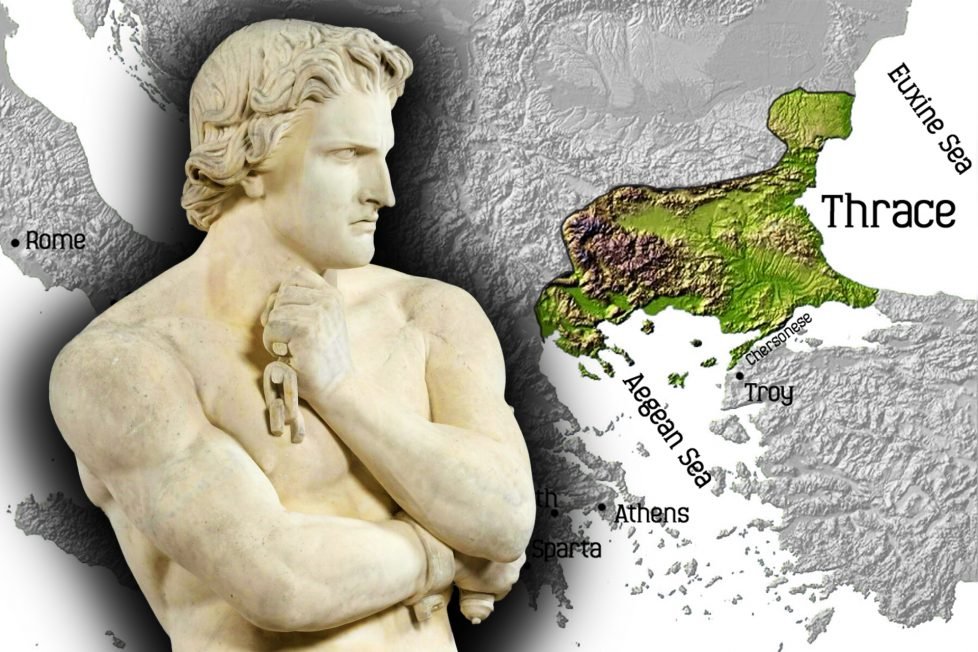

Although most of Thrace did eventually unite under a single leader, by that time, it was a different world than the one Herodotus wrote about, and the aftermath was far less profound than he envisioned. Even in the absence of political unity, the tribes inhabiting the hills and forests between the Aegean and the Black Sea formed a unique culture that left a significant mark on antiquity.

Almost half a century after Spartacus’ demise Rome became a fully-fledged empire, with Thracia (as Thrace was called at the time) as its client kingdom. The reformed Roman state was in search of a more glorious pedigree; thus the emperor had the greatest poet of his time write an epic that will not only emulate Iliad in its style but would, in a way, be its sequel. While Virgil’s Aeneid aimed to tie Rome’s history to that of the Trojan War, for Thrace this connection was made by Homer himself.

The war, which allegedly took place sometime in the 12th century BC, saw Thracians as Trojan allies. Homer mentions four Thracian kings by name in the Iliad, possibly all leaders of different tribes with their own contingents of warriors. King Rhesus is described arriving on the battlefield in “his chariot bedecked with silver and gold, bearing his marvelous golden armor, a rare workmanship too splendid for any mortal to carry, and fit only for the gods.” This same equipment was later taken from him by none other than Odysseus, while Diomedes killed the king himself, during the same night raid on the Thracian camp.

From the Odyssey, we learn that Ares, the Greek god of war, calls Thrace his home. It is likely that Thrace itself derived its name from Ares’ son, Thrax, about whom we know little today. Unlike his Roman counterpart, Mars, Ares was not widely respected and actively worshipped in most parts of Ancient Greece, as he was viewed as the god of excess and all that was terrible about war. However, in Thrace, Herodotus noted, “they worshipped no gods but Ares, Dionysos, and Artemis.”

Despite their warlike nature, admittedly overemphasized by Greek playwrights and historians, it was neither a warrior nor a famed war-lord that became the most well-known Thracian from the Age of Myth. It was instead “the father of songs” (as Pindar called him) Orpheus, son of a Thracian king and the Muse Calliope. If myths are to be believed, Orpheus played his lyre so well that it persuaded Hades to release his wife Eurydice from the underworld. Furthermore, his music overpowered the song of the Sirens, allowing the Argonauts to continue their quest for the Golden Fleece.

In the typical orientalist fashion of the time, the Greeks considered those whose language and lifestyle differed from theirs as barbarians. In this respect, polygamous and horse-riding Thracians were no exception. Furthermore, in contrast to polis dwelling Greeks, most Thracians lived in scattered villages and hamlets, since Thrace was utterly deprived of large cities. Gradual Greek colonization of the Thracian coast, which started in 8th century BC, did little to change the Hellenic view of their neighbors. The new Greek cities were simply included into constant inter-tribal warfare of the region.

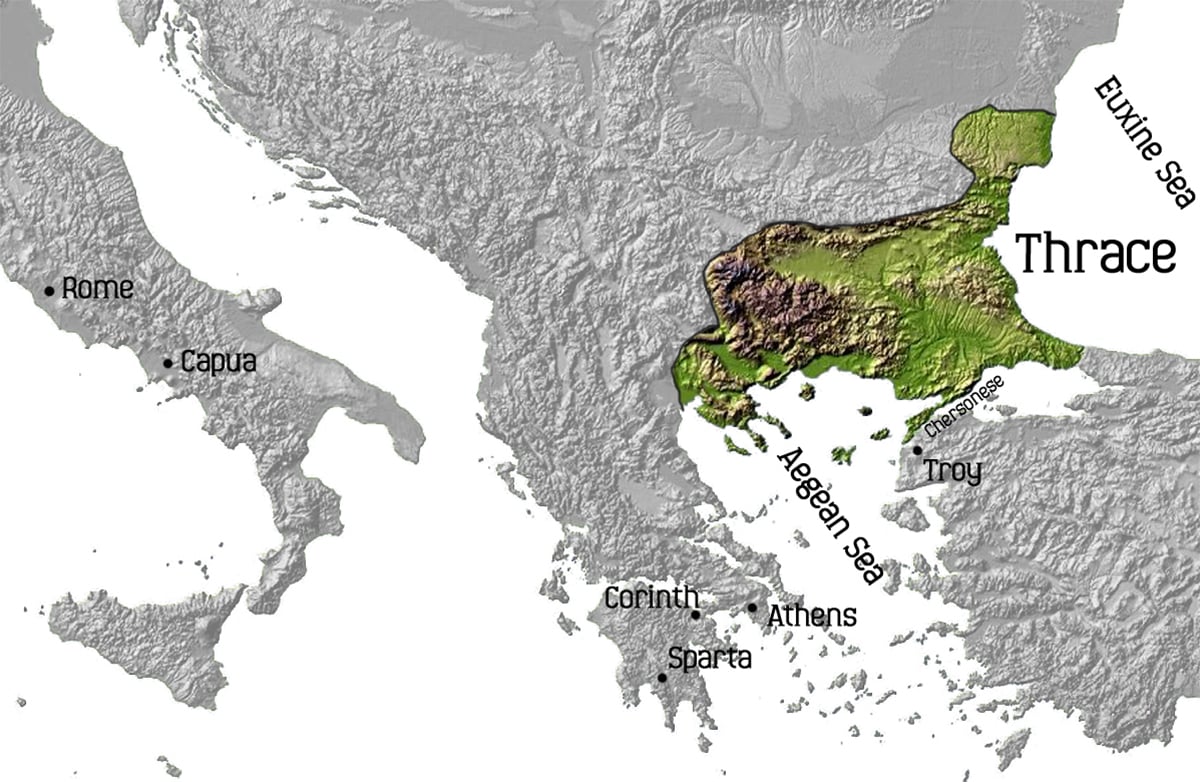

To illustrate this point, Herodotus describes one significant event of the Greco-Thracian interaction from the mid-6th century BC. The Thracian tribe of Dolonci, which was about to be pushed out of their native peninsula by the rival tribe of Apsinthians, sent envoys to Athens seeking assistance. Miltiades the Elder, of the Athenian aristocratic family of Philaidae, answered the call. He sailed across the Aegean with a contingent of warriors and settlers. According to Herodotus, “his first act was to wall off the isthmus of the Chersonese from the city of Cardia across to Pactye, so that the Apsinthians would not be able to harm them by invading their land.”

With security issues out of the way, Miltiades established several Greek colonies in the area and became the tyrant of the so-called Thracian Chersonese. The peninsula was of tremendous strategic significance since it controlled sailing routes to the Black Sea (or the Euxine Sea, as it was known to the Greeks). It was ruled by Miltiades’ dynasty until the arrival of the Persians a century later.

Miltiades had an additional incentive for leaving Athens as the polis was ruled by Peisistratos, a tyrant that did not value potential competition. Peisistratos himself employed Thracian mercenaries as his bodyguards, who would on occasion act as secret police dealing with his political enemies outside the public eye. Although Greco-Thracian cultural interaction was mostly martial in nature, the presence of Thracians in Athens was increasingly felt in all forms of Attic art. From the time of Peisistratos’ tyranny onward, for example, the distinctly Thracian cloak (zeira) and fox-skin caps (alopekis) could often be seen as an attire choice of vase-painted figures.

The next century saw a military revolution brought about by Thracian mercenaries. While Greek armies preferred to use their famed heavy infantry, the hoplites, Thracian tribes waged warfare with cavalry and lighter infantry units. Thucydides, who himself was a general in the Peloponnesian War, reports a heavy defeat suffered by some 450 Spartans stranded on the island of Sphacteria in the wake of the Battle of Pylos (425 BC). Throughout the battle, lightly armed Thracian skirmishers, called peltasts (named after crescent-shaped wicker or leather shields called peltes), harassed Spartan troops with javelins and stones. However, when the heavily armed hoplites attempted to engage the lighter Thracian troops, the Thracians would simply retreat and then return to launch another volley of projectiles.

Although the 300 Spartans who surrendered complained about the tactics as being dishonorable, the utility of light infantry was proven beyond any doubt. Three decades later, during the Corinthian War, a force composed entirely of Athenian peltasts won the Battle of Lechaeum (391 BC) against a force made entirely of Spartan hoplites. In the Hellenic world, this is the first known account of heavy infantry being defeated by a force composed of light infantry alone. By this time, the Greek peltasts so closely resembled their Thracian predecessors in appearance that they were often confused, both by contemporaries and archaeologists today, with Thracian mercenaries.

Most Thracian tribes, having no stake in the Greco-Persian conflict, submitted to the Achaemenid Empire peacefully. This was the first time the Thracians were exposed to something akin to an organized state. Although no great feats of infrastructural construction are known in this period, Thrace experienced the cessation of tribal warfare and, with it, a flourishing of trade. Its inhabitants were exposed to taxation but also to advanced manufacture and coin minting, laying down the groundwork for a proper government.

When the Greeks managed to push the Persians out of Europe, the vacuum of power in Thrace was quickly filled by the native Odrysian dynasty. What started off as a federation of tribes under King Teres, “the founder of the great Odrysian empire,” soon “extended over a large part of Thrace, although many of the Thracian tribes were still independent.” The territory covered by the Odrysian Kingdom henceforth became synonymous with Thrace.

Rich with ore and timber (a major supply for the Greek shipbuilders) the Thracian Kingdom flourished. With prosperity, however, came an internal power struggle. In a sort of reversal of the situation from the previous century, now Greek heavy infantry was in demand among Thracian leaders seeking some edge over their rivals. A student and a friend of Socrates, Xenophon, personally led a band of hoplite-mercenaries during one of these wars. What Xenophon witnessed was the beginning of the fragmentation that, half a century later, made the Thracian kingdom easy prey for the expansionist Macedonian ruler Philip II.

Like most of the Greek states, the Thracian kingdom proved no match for the Macedonian phalanx and their brilliant commander. Philip II managed to turn Thrace into a Macedonian vassal state before he was eventually assassinated by one of his own men. Vassalage to Macedonia did not end with Philip’s death, and Thracian warriors participated in his son’s conquest of the East.

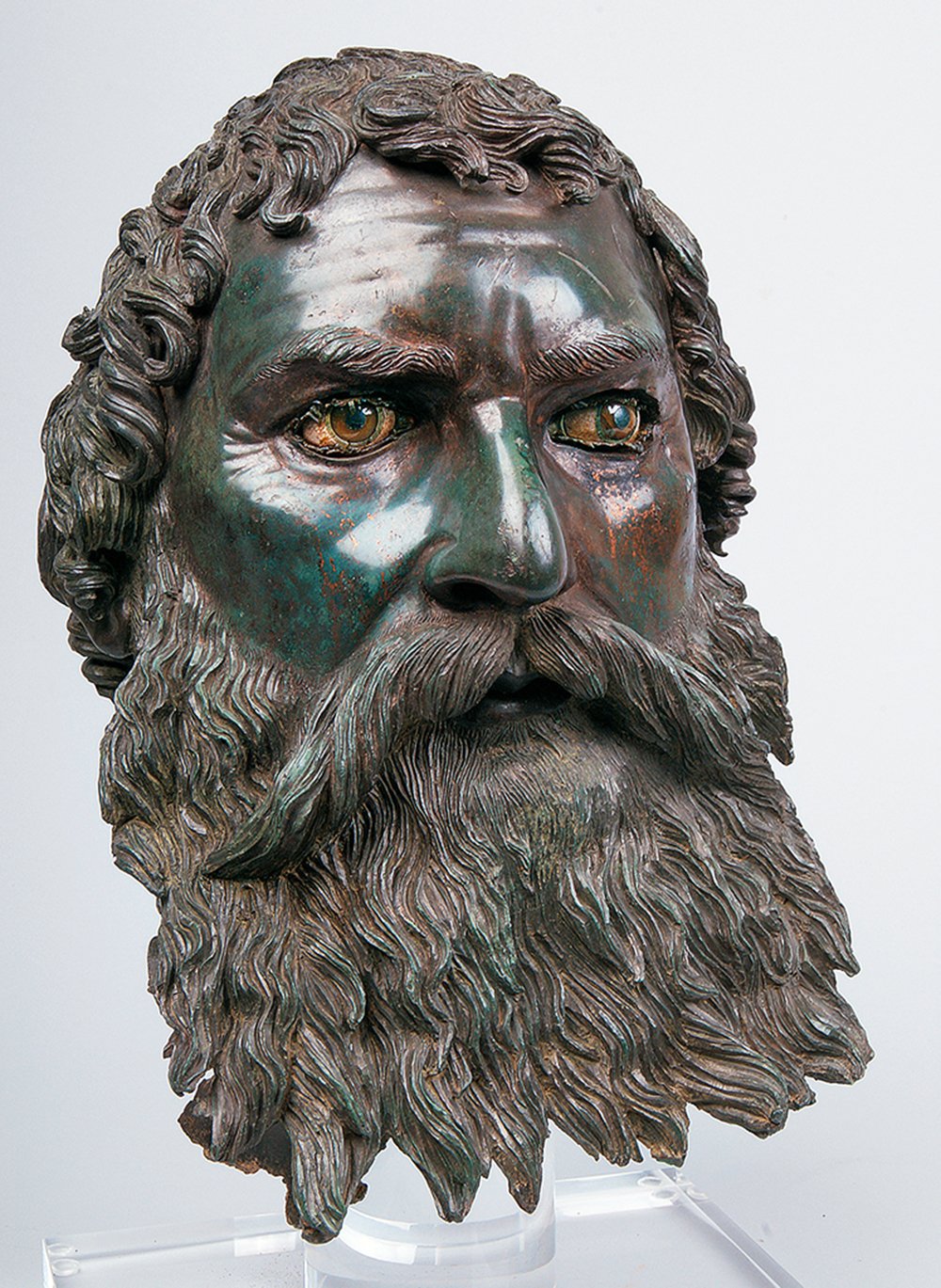

After Alexander the Great’s death, however, Thracian rulers managed to regain some degree of autonomy despite remaining vassals of his Macedonian successors. Lack of political independence did not hinder the cultural development of Thrace. Some of the most monumental princely tombs, such as that of Seuthes III, are dated precisely to this period. Their size and intricate decoration speak as much of their inhabitants’ significance and wealth as they do of their craftsmen’s skill.

Nonetheless, vassalage to Macedon indirectly led to the demise of the Thracian state and culture. Thrace was obliged to participate, as a Macedonian ally, in four disastrous wars against the Roman Republic. After the Battle of Pydna (168 BC), which ended the Third Macedonian War, Rome had finally taken over Macedon and, by extension, Thrace became a client state of the Roman Republic. Following a series of revolts, as well as the Fourth Macedonian War, Rome decided to depose the ruling dynasty in Thrace and appoint one that would repay the Romans with loyalty. One such dynasty were the Sapaeans, who ruled Thrace at the time when Spartacus came into prominence.

By the first century BC many Thracians became Hellenized, as they started living in cities and increasingly interacting with neighboring peoples. There were, however, still tribes that lived in the old Thracian ways that predated the kingdom and its conquest. Among these were the Maedi, the tribe Spartacus came from, according to the Greek and Roman historians.

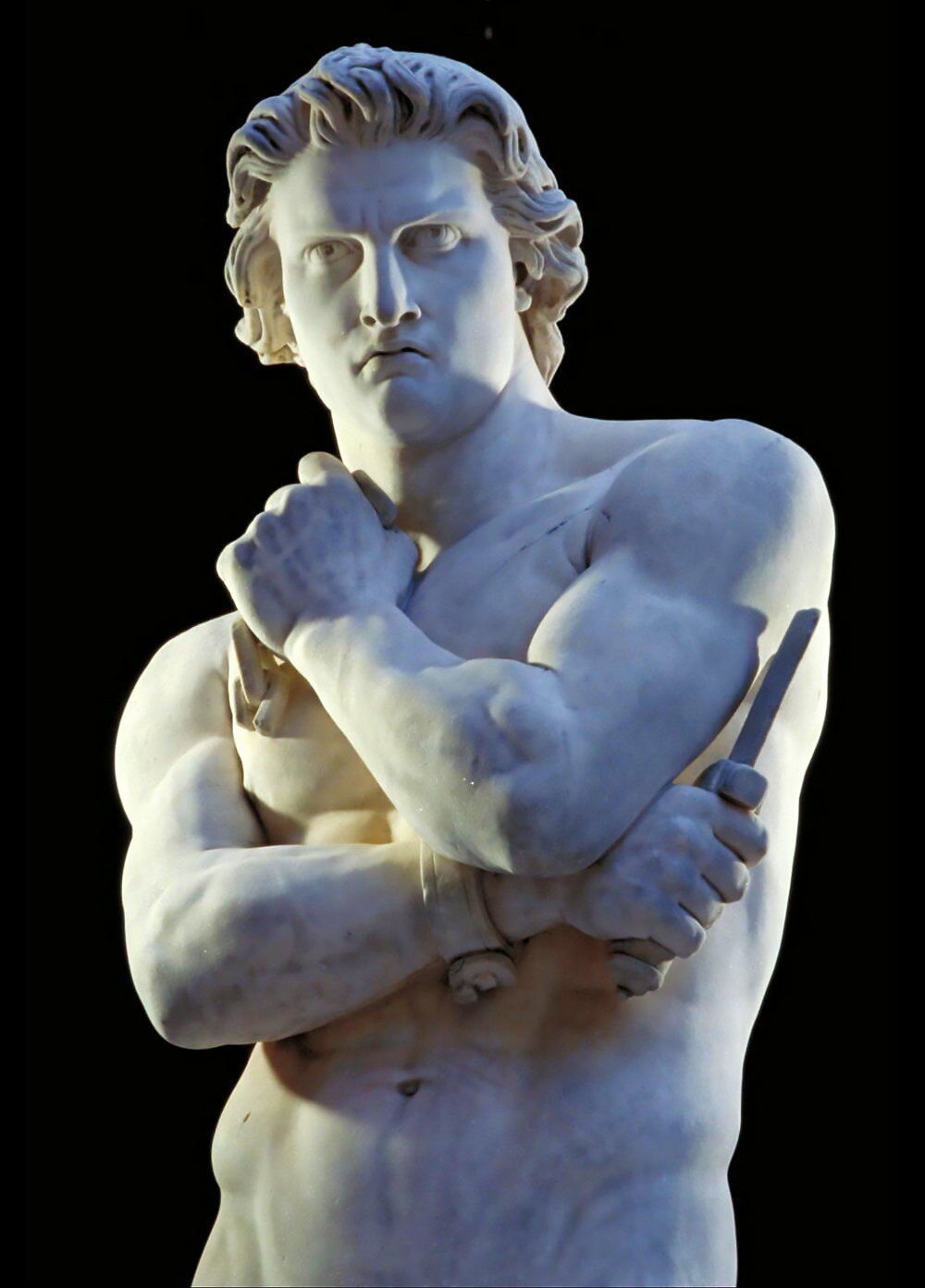

At the time, the Auxilia was not yet formally established, but people from client kingdoms, such as Thrace, could serve in the Roman military as a complementary force of specialists. Most often, these were cavalry units known as alae. According to Appian, Spartacus “had once served as a soldier with the Romans,” but ended up deserting only to be captured and sold as a slave. In 73 BC, Spartacus was at a gladiator school in Capua when he incited 30-70 fellow slaves to escape. Eventually, Spartacus amassed an army of more than 100,000 slaves, which made him the most famous Thracian leader, although he never led an army of Thracians or in Thrace.

Spartacus’ initial success was partially due to the fact that at the time of his revolt, all legions were outside of Italy, dealing with other rebellions. Spartacus managed to defeat both consuls for the year 72 BC; nevertheless, in 71 BC, his luck ran out. Spartacus was finally defeated by Crassus, the richest man in Rome, who led six legions against the army of slaves. Although it is assumed Spartacus died in battle, his body was never recovered, only adding to the warrior’s legend.

A century later, under Emperor Claudius, Thrace was annexed by the Roman Empire becoming a fully-fledged province. Henceforth, Thracian culture slowly started to dissolve as Thracians gradually became Romans. However, it did not happen overnight, Thracian language was not fully extinct until 6th or 7th century AD. Although there are no Thracians alive today, Thracian heritage is claimed by the Republic of Bulgaria. Indeed, Bulgaria covers a large portion of what was once the Thracian kingdom, and archaeological reminders that a great ancient civilization dwelled there are constantly being discovered all across the land.