8 of History’s Biggest Business Scams and Frauds

From Mesopotamian swindlers to 19th-century snake oil salesmen, crooks have always been a menace.

From Mesopotamian swindlers to 19th-century snake oil salesmen, crooks have always been a menace.

Table of Contents

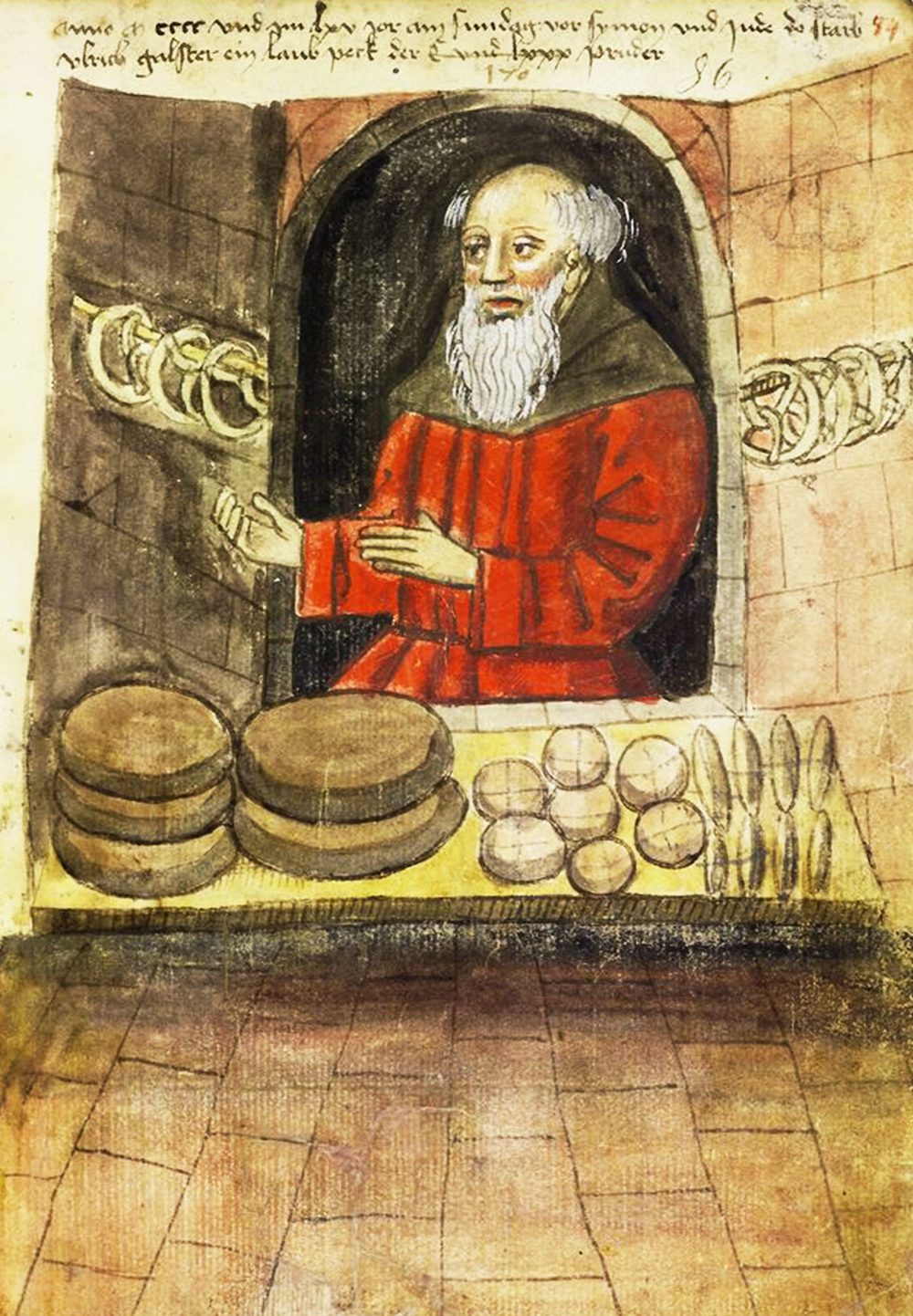

ToggleA scandal that ran rampant from the Middle Ages until well into the 19th century in pretty much every part of the settled world. For centuries bakers who fell on hard times, mixed harmful substances such as sawdust, chalk, alum, dirt and even arsenic into their bread and flouted government-imposed regulations at the expense of public health.

Dodgy dough-dealers down on their luck would go to amazing lengths to get around the rules, with one 14th century baker from London even having the audacity to insert iron bars into his loaves to make them weigh more.

Fortunately, the practice was eventually stifled by stricter inspections and increasing consumer awareness of the issue throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, putting a stop to poisoned bread once and for all.

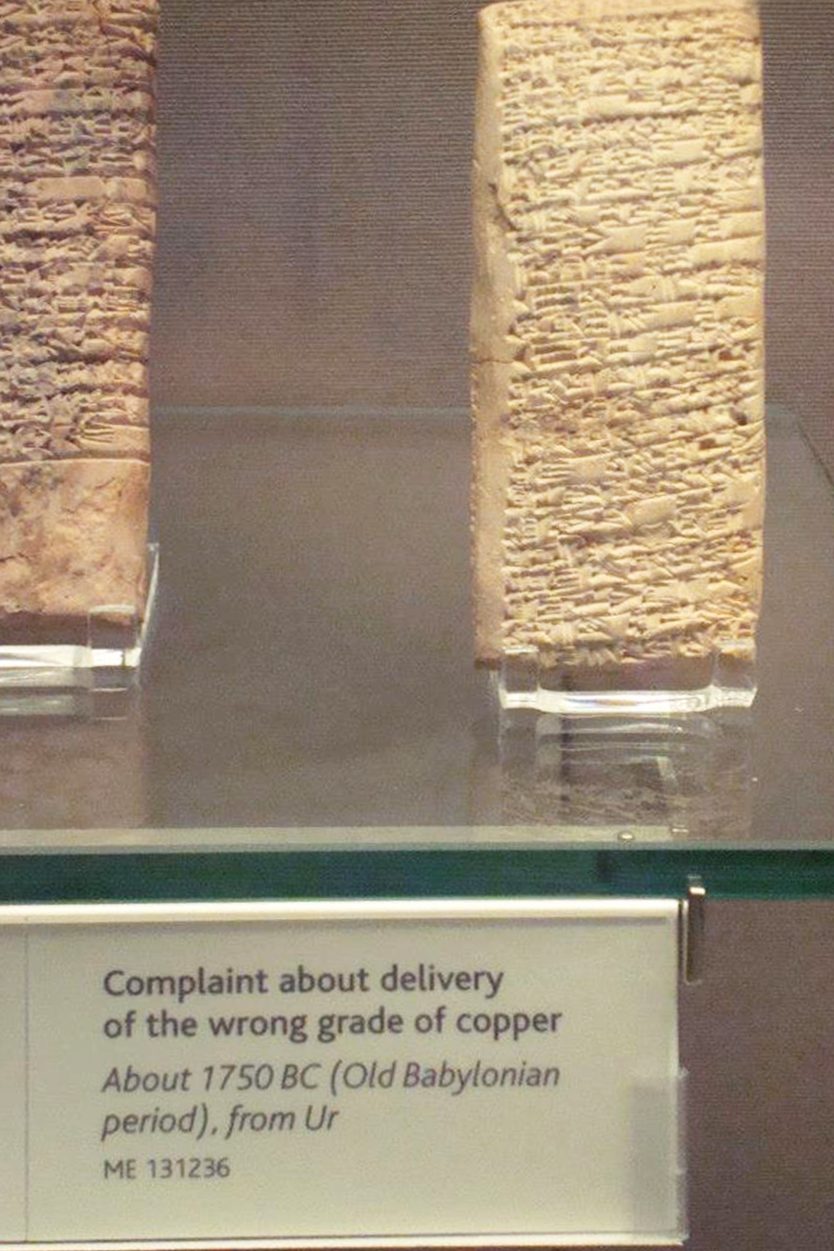

In 1750 BC the first recorded complaint in human history was made by an individual called Nanni, who accused a merchant of selling him a batch of sub-standard copper and of acting aggressively towards his servant when the issue was raised.

It’s clear that Nanni was dealing with a serial swindler, since several other tablets with similar complaints were also found in the house of Ea-Nasir, a hustler of the craftiest degree who was known for changing his business every time he was found out.

Today ancient Mesopotamia’s smoothest operator has gained somewhat of cult status online, becoming a popular meme and the personification of the shady businessman. He may have even been up to his old tricks in 2021, when a Turkish trader delivered painted rocks instead of 36 million dollars of copper – Ea-Nasir strikes again?!

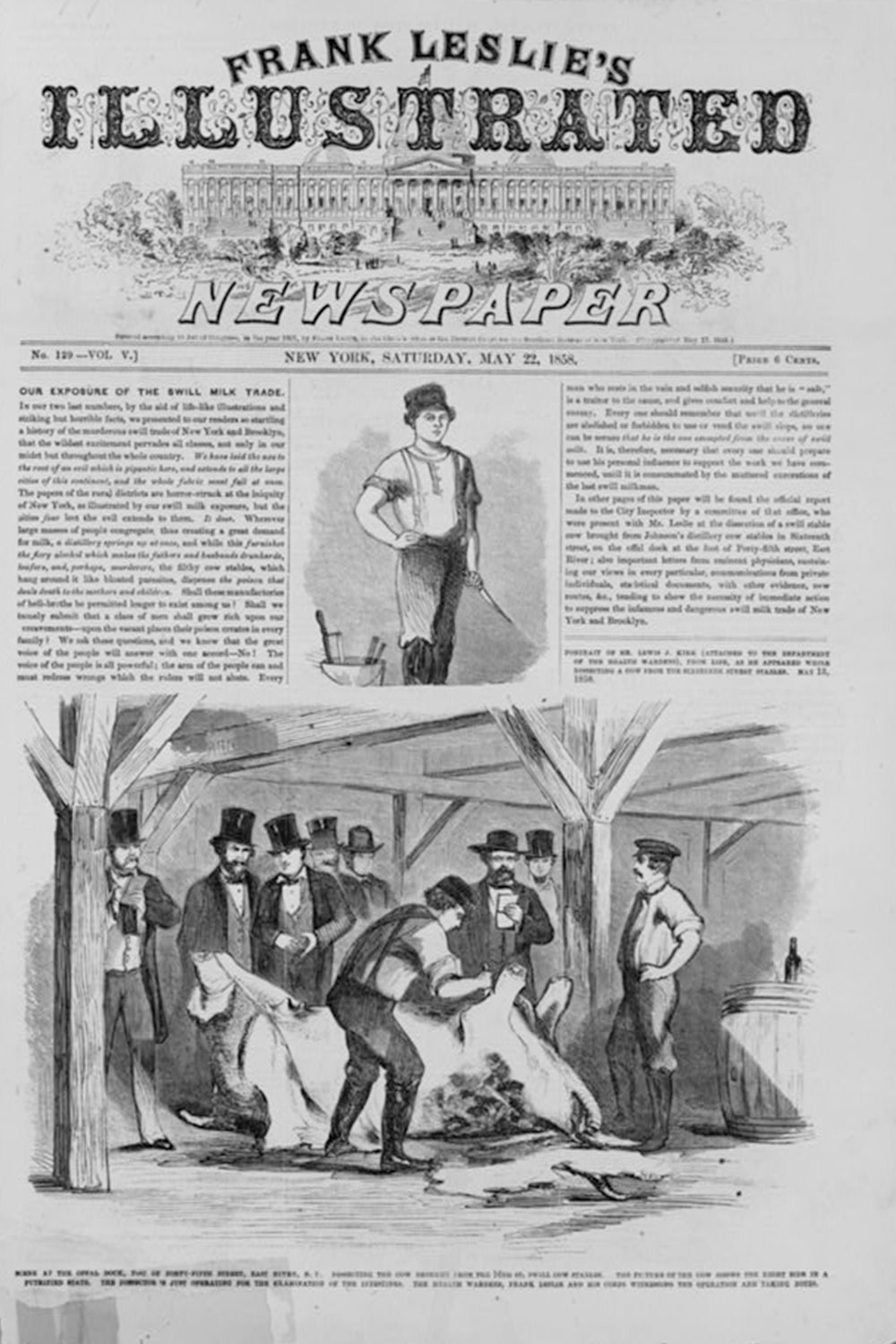

An udder tragedy, in 1858 the news that dicey dairy was responsible for the deaths of thousands of infants plastered the headlines of almost every American newspaper.

Investigative journalist Frank Leslie revealed the shocking truth in a series of devastating exposes, which affirmed that defective milk was to blame.

Eager to capitalize on the growing public appetite for fresh cow’s milk, dishonest whiskey distillers had attached cow sheds to their factories, exclusively feeding their livestock waste product known as ‘swill’, a substance so noxious it caused the animal’s tails to fall off.

The resulting ‘swill milk’ was nauseatingly blue, causing vendors to add additives such as chalk, flour, and eggs to make it look more natural. Thanks to Leslie’s crusade though, in 1862 a new set of milk regulations were passed and swill milk disappeared down the drainpipe of history.

For time immemorial charlatans have been crafting fake versions of Ancient Greek relics so convincing they can even bamboozle the experts.

One of the best known examples involves the Tiara of Saitafene, which was initially believed to be a gift given to the Scythian King Saitapharnes from the ancient Greek colony of Olbia on the Black Sea, in the 3rd century.

Presented to the prestigious Louvre Museum in April 1896 by two sketchy Russian art dealers and bought for an extortionate 200,000 francs, it later transpired that the tiara had actually been crafted by a master goldsmith by the name of Israel Rouchomovsky who thought he was making it as a gift for an archaeologist.

Even now inauthentic pottery is still causing havoc. For example, among the artifacts handed over to the Greek government this year from the stolen collection of disgraced British antiquities dealer Robin Symes, is a vase proven to have been forged in the 1990s using shards of worthless authentic material.

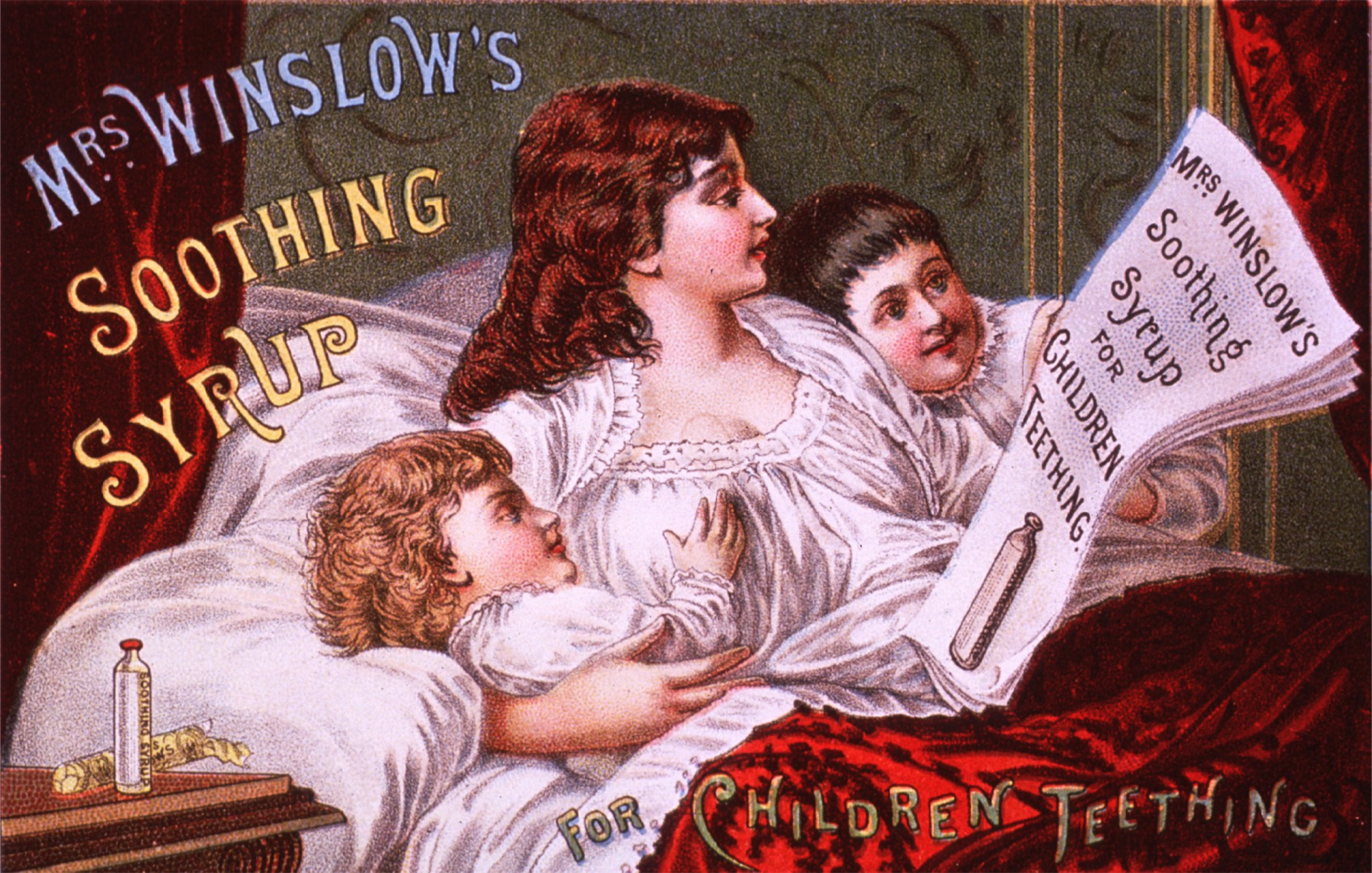

Although laws prohibiting quackery were first enacted as early as the 16th century, selling counterfeit medicines continued to be a popular scam right up to the Victorian period.

During the 18th century this pseudo-medical malpractice was at its height, with many devilish defrauders willing to take advantage of the working class’ general ignorance of science.

Among their ranks was Adam Donald, a man of humble origins also referred to as the ‘Prophet of Betheline’, who gave his gullible patients some bizarre prescriptions, ranging from milk baths to singing on chimneys.

At the other end of the socio-economic ladder was John Hill, a man who exploited his distinguished academic background to peddle herbal remedies to ill-educated buyers such as his ‘Pectoral Balsam of Honey’, advertised as a cure for all breathing and throat conditions.

By the 19th century quackery had even taken hold in the United States, where many baby medicines fortified with morphine, opium and even cocaine were prescribed with tragic consequences.

Propelled by the rapid expansion of the shipping industry, from the 18th century maritime insurance became a lucrative business, enriching not only the brokers that issued such protections but unscrupulous opportunists seeking to exploit them.

Crooks often purposely sank their ships and collected the insurance money because the crime was very hard to detect, and if such an act was discovered it was often the result of pure coincidence.

In 1820, a Glasgow merchant by pure chance saw some of his lost cargo being sold in a shop window, leading to the uncovering of a crime committed by his ex-business partner, John McDougall, who had profited from the proceeds of 8 insurance policies.

But although peaking in the 19th and 20th centuries, oceanic offenses of this ilk have actually been around for eons. One of the first recorded instances of financial fraud was maritime in nature, dating back to 300 BC when a Greek merchant called Hegestratos attempted to capsize his own boat to claim money on a maritime loan known as bottomry.

However the guileful Greek would never be able to cash in when, caught in the act, he was drowned by his crew and passengers.

As a result of high profile cases such the Grenfell Tower fire and the Surfside condominium collapse, construction fraud has been thrust into the spotlight in recent years.

Yet the need to cut corners for higher profit margins is an age-old crime, dating back to the Ancient Romans. At that time quarry bosses often instructed their employees to dig out the more easily attainable top layers of marble despite the fact that they were usually riddled with holes.

Although this substandard material was a lot weaker than the deeper and more labor-intensive stone, contractors sold it off anyway, leading to a string of disastrous building collapses. In response the government passed a law requiring workmen to write the phrase ‘sine cera’ or ‘without wax’ at the end of their invoices to assure the quality of their product.

If the building fell to pieces the marble-producer became the architect of his own demise, and was promptly executed by the state.

With the opening up of trade routes from Europe to Asia during the Age of Exploration, spices and other exotic commodities became worth their weight in gold, compelling many rip-off artists to season their own goods with sprinkles of deception.

Ground pepper was one such popular ware that was often adulterated with cayenne, rape seeds, potato scraps, gypsum, and even ‘pepper dust’, which was basically the floor sweepings of pepper warehouses. Sawdust was another common additive that could be mixed into most spices, as was pretty much any substance that matched the color of the ingredients such as cinnamon, which could be augmented with cassia.

Another profitable product that could be tampered with was tea, with importers sometimes adding gypsum, clay, and even iron fillings to increase the weight of shipments. In fact, so riled up were the British by this that during the reign of King George I a law was passed that forbade the mixing of tea under penalty of seizure and a 100 pound fine.

So whether it be bad bread, crummy copper, deadly dairy, measly medicine, lucrative loans, a cut-price brick, or a sham spice mix, almost every product available has been made fraudulently saleable by the hawkers and hucksters of history.