What Is Pop Art? A Look Beneath the Surface

Pop art — an art movement that is more meaningful than just comic books or colorful ads.

Pop art — an art movement that is more meaningful than just comic books or colorful ads.

Table of Contents

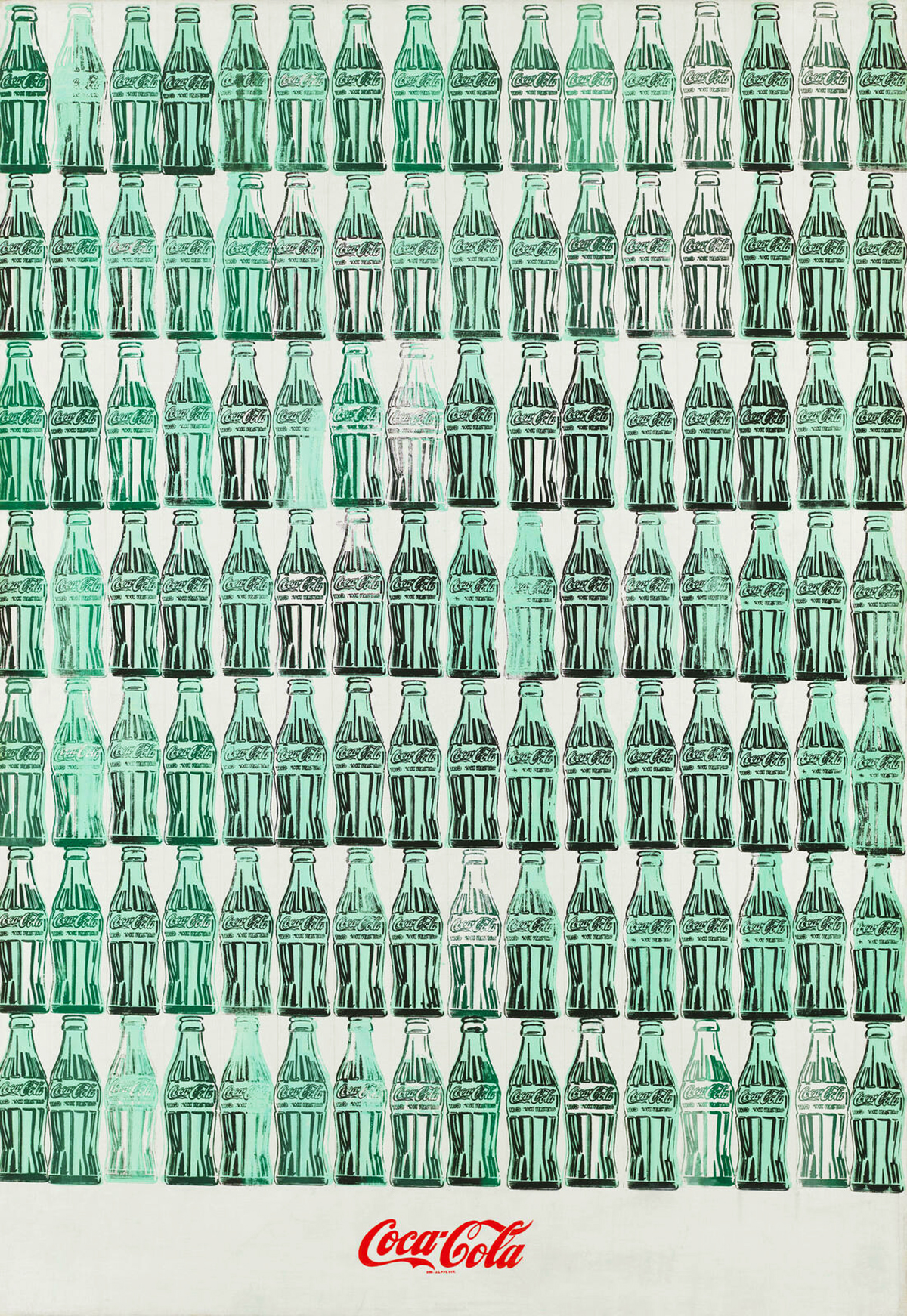

TogglePop Art is one of the most instantly recognizable art movements. Built to be universally understandable for anyone within the American consumerist system, Pop Art soon developed a life on its own. Andy Warhol’s images of Coca-Cola bottles gained perhaps the same popularity as their mass-produced original, and his portrait of Marylin Monroe gained a life disconnected from its real inspiration.

Through the lens of an average museum-goer, Pop Art frequently appears as oversimplified kitsch, loud and bold art expressing nothing substantial. However, the development of Pop Art was not only reasonable but utterly logical in the wider context of Western art history. Today, we will look for a more profound message under the enthusiastic superficiality of Pop Art.

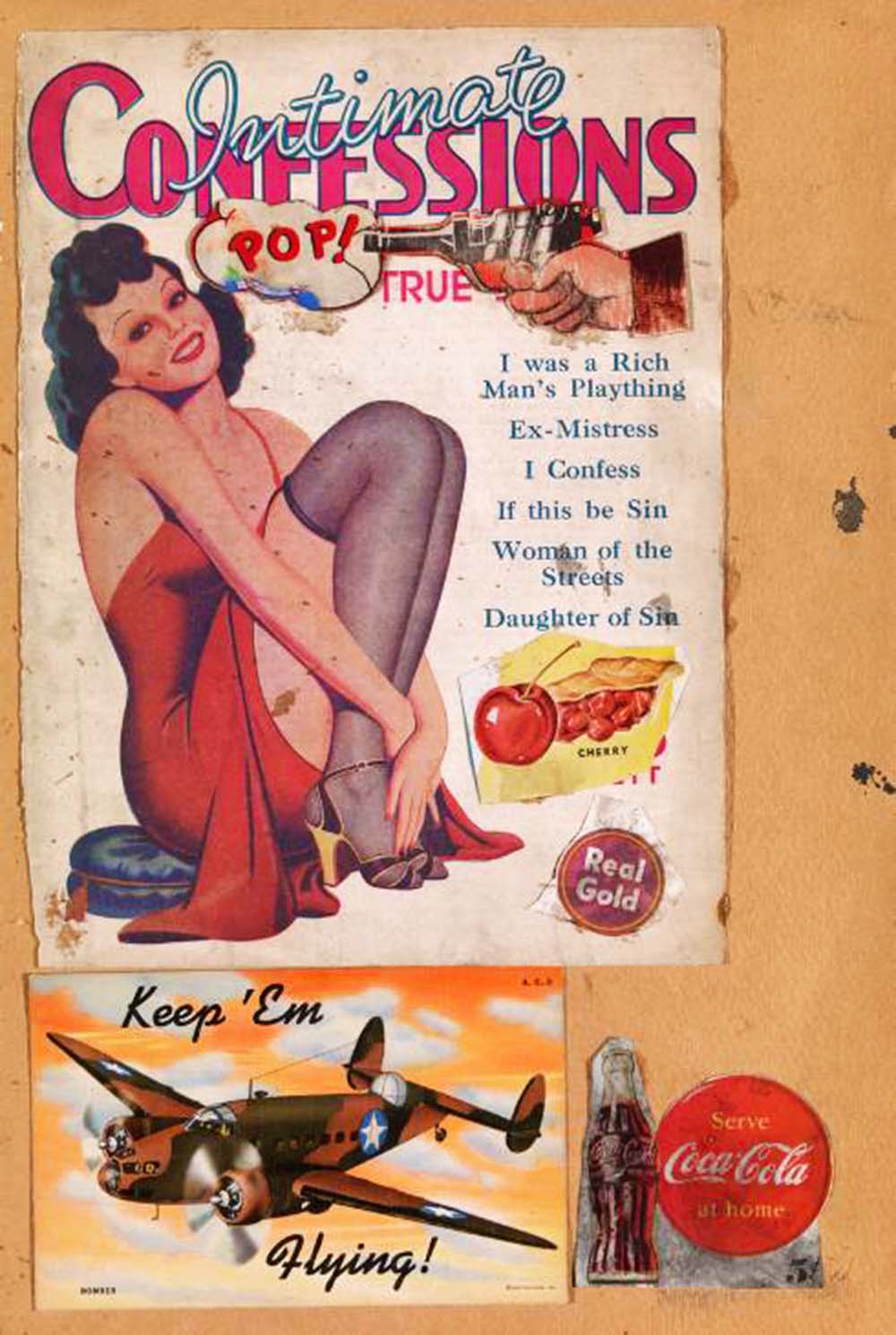

The first artist to create a Pop Art work was Eduardo Paolozzi, whose collage I Was a Rich Man’s Plaything gave rise to the entire movement, although not immediately. Paolozzi was a Scotsman of Italian descent whose contact with American culture happened in post-war Paris in the late 1940s. American presence during the war left its mark in the form of magazines and newspapers, and Paolozzi, who resided in the French capital at the time, amassed a collection of cutouts, which he started to rearrange to build new narratives. Originally, Paolozzi had no intention to present his collages to the public, using them as references and inspiration points for his other paintings. His version of Pop Art was not a direct reflection of American culture but the impression it made on British audiences. Paolozzi’s work was rough at the edges, composed of faded and stained cutouts, makeshift, and distinctively handmade.

By the 1960s, Pop Art had crossed the ocean and returned to its conceptual homeland. American artists gave the movement plastic gloss and the allure of a freshly produced product from a supermarket shelf. Art became everything, and everything became art: soup cans, celebrity photos, comic strips, giant burgers, and American flags.

However, some experts trace the origins of Pop Art to the post-World War I Dada movement that flourished both in New York and Paris. Dada celebrated life’s absurdity in the face of worldwide catastrophe and the pointlessness of life. One of the distinctive Dada art forms was readymade sculpture created from found objects with little to no involvement from the artist. One of the most famous Dadaists to promote readymades was Marcel Duchamp, who scandalized Parisian art critics with a stolen urinal as his latest sculpture.

As well-established, unserious, and apolitical as Pop Art may seem, it did not pop up – no pun intended – from nowhere. To better understand its reasons for emerging and gaining immense popularity, we need to look at the art world a decade or two earlier.

In the 1950s, the American art scene was dominated by Abstract Expressionism. The movement, promoted by art critic Clement Greenberg and his group of wealthy New York intellectuals presented a radical approach, claiming that complete abstraction was the only legitimate version of art. At the heart of Abstract Expressionism lay the highly personalized artistic expression of a single individual. Its hyper-intellectualism made the movement exclusive and inaccessible to the larger public, requiring an understanding of philosophical and metaphysical matters.

The main faces of Abstract Expressionism were troubled and tragic male heroes, aggressively masculine and self-centered. Self-destruction was believed to be a side effect of their genius: the undisputed leader Jackson Pollock battled alcohol addiction and died in a car crash while others like Mark Rothko or Archille Gorky took their own lives.

In that contest, radical and liberal materialism of Pop Art opposed the high-brow elitist intangibility of Abstract Expressionist canvases. Pop Art was simple, understandable, and full of enjoyment – both a celebration of the contemporary age and a quirky joke about it. Although Pop Art’s main heroes were also men, they offered a different approach to masculinity and human involvement in the artistic process. Instead of the personality-oriented egocentric act of creation represented by Pollock and his followers, his complete opposite, Andy Warhol, dissolved in his own work. Warhol was everywhere and nowhere – his public appearances, his looks, and his contradicting statements barely provided the audience with plausible information about the artist’s real character and personality. His art was universally understandable partly because he chose to eliminate himself from it.

Obviously, one art movement did not immediately die off after the appearance of another. Thus, Abstract Expressionists and Pop Artists had plenty of time and opportunity to mock and offend each other. For several years, both groups met in the same bar – Cedar Tavern in Greenwich Village – and shared many remarkable encounters. Rumors said that Jackson Pollock repeatedly tried to kick Andy Warhol out of parties but to no avail.

The universal accessibility of Pop Art was part of its appeal. As Andy Warhol once formulated, in America, no amount of money could bring you a bottle of Coca-Cola better than the one anyone can get at every grocery store. Likewise, no amount of education and elitism could turn a Pop artwork into something conceptually different.

In a way, the inclusive message of pop art reflected the changing landscape – both societal and literal. Before, artists painted their environments in the form of trees, mountains, rivers, and other natural scenes, and later, with the advent of modernity and Impressionist art, cityscapes. The time of Pop Art had one particular feature that made it special: the omnipresence of advertisement, cheap disposable goods, and ways to spend your money. Consumption became the new lifestyle and the central activity. In that sense, Pop art painting reflected the immediate reality of Western citizens and represented the contemporary landscape in its purest form.

Moreover, the use of comic book strips, newspaper headlines, ads, and magazine illustrations gave an uncanny feeling to seemingly cheerful art. A viewer ready to look behind the glossy surface, quickly noticed the divide between reality and the plastic perfection of advertisement. Swedish-born sculptor Claes Oldenburg reconstructed grocery shops and hotel rooms from plaster and vinyl. Appealing at first, the viewer would feel increasing discomfort while staring at artificial substitutes of reality.

One of the most prominent features of Pop Art is its inherent self-contradiction. While attempting to democratize art, it turned its artists into unapproachable global celebrities and sold the endlessly reproduced prints of regular consumer goods for millions of dollars. They placed objects of ‘low’ popular culture in the spot reserved for high-end, exclusive, and sophisticated content. This move forced intellectuals and art lovers to devise explanations and look for deeper meanings in simple objects – ironically, what we are doing right now!

As Pop Art celebrated abundance and consumption, it also ridiculed it using the same tools and methods. Some art historians link Pop Art compositions to the European tradition of vanitas painting – allegorical still-lives aimed to remind the futility of earthly pleasures and imminent death.

Usually, vanitas would feature food, flowers, expensive jewelry or exquisite silverware, books, and scientific instruments. Among recurring features were mirrors as symbols of vanity and skulls or bones. Perhaps the most important parts of vanitas compositions, skulls, were reminders that death did not discriminate between rich and poor, beautiful and ugly, educated and illiterate. The outcome would inevitably be the same for everyone regardless of their worldly possessions. The only thing that would count in the afterlife, according to vanitas painters, was spiritual purity and fear of God’s wrath.

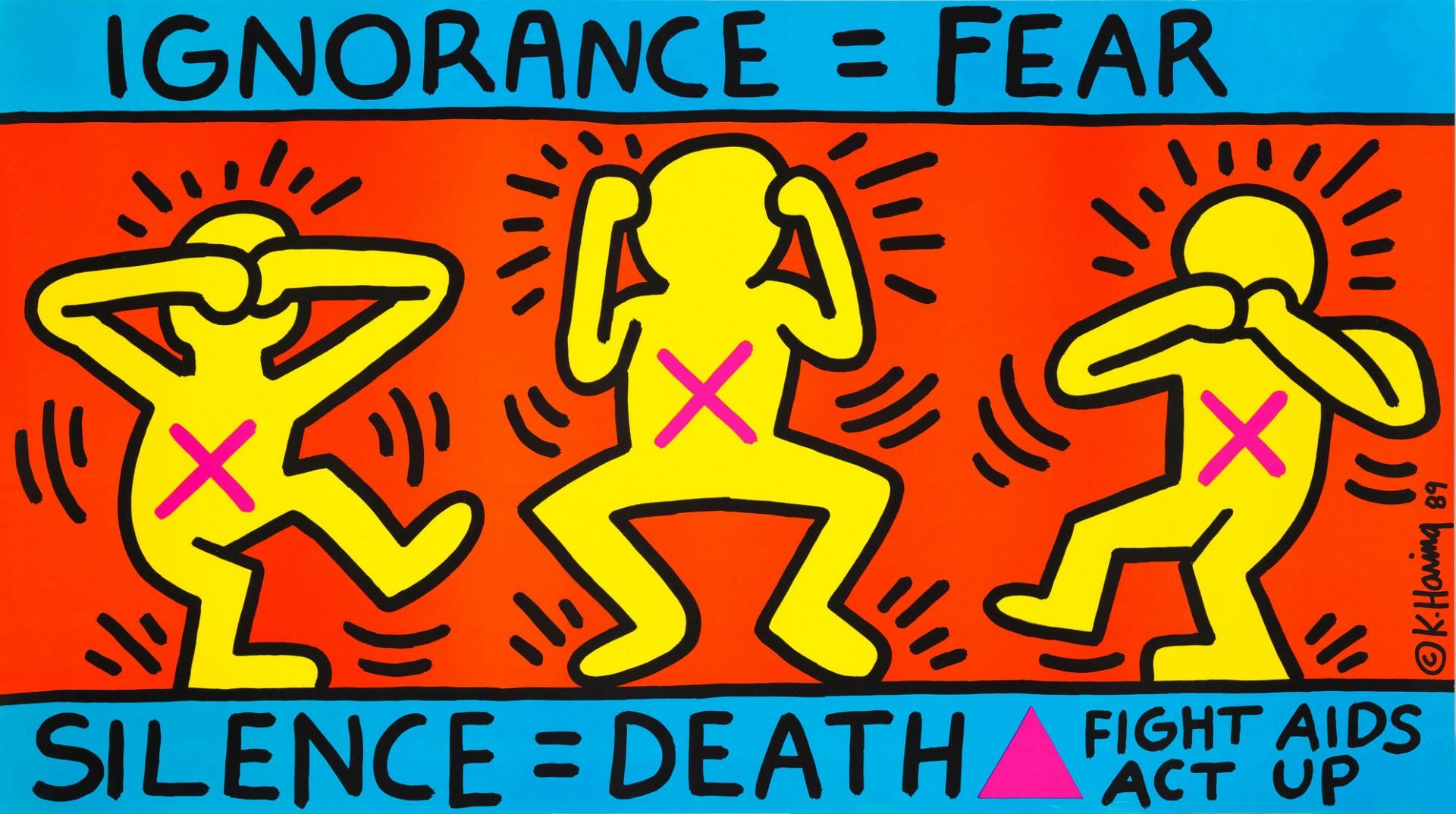

Although Pop Art never concerned itself with divine punishment, it nonetheless hinted at the pointlessness of the plastic carnival and mass-consumerism escapism. Warhol’s portraits of Marylin Monroe crack, tear, and fade with every reproduction as if diluting the real person behind the celebrity image while Keith Haring’s colorful comic strips hide a plea to help solve the AIDS crisis.

Despite the American basis of Pop Art, over the years, it was spread well over the borders of the country, soaking in cultural and regional nuances. In the 1970s, underground Soviet artists devised their own version of Pop Art. Instead of Western capitalist imagery, it relied on the mass culture of the Soviet states, portraits of leaders, and household items. Soviet Pop Art, known under the name of Sots-Art, was not a celebration but a direct mockery of authorities and their restrictive policies.

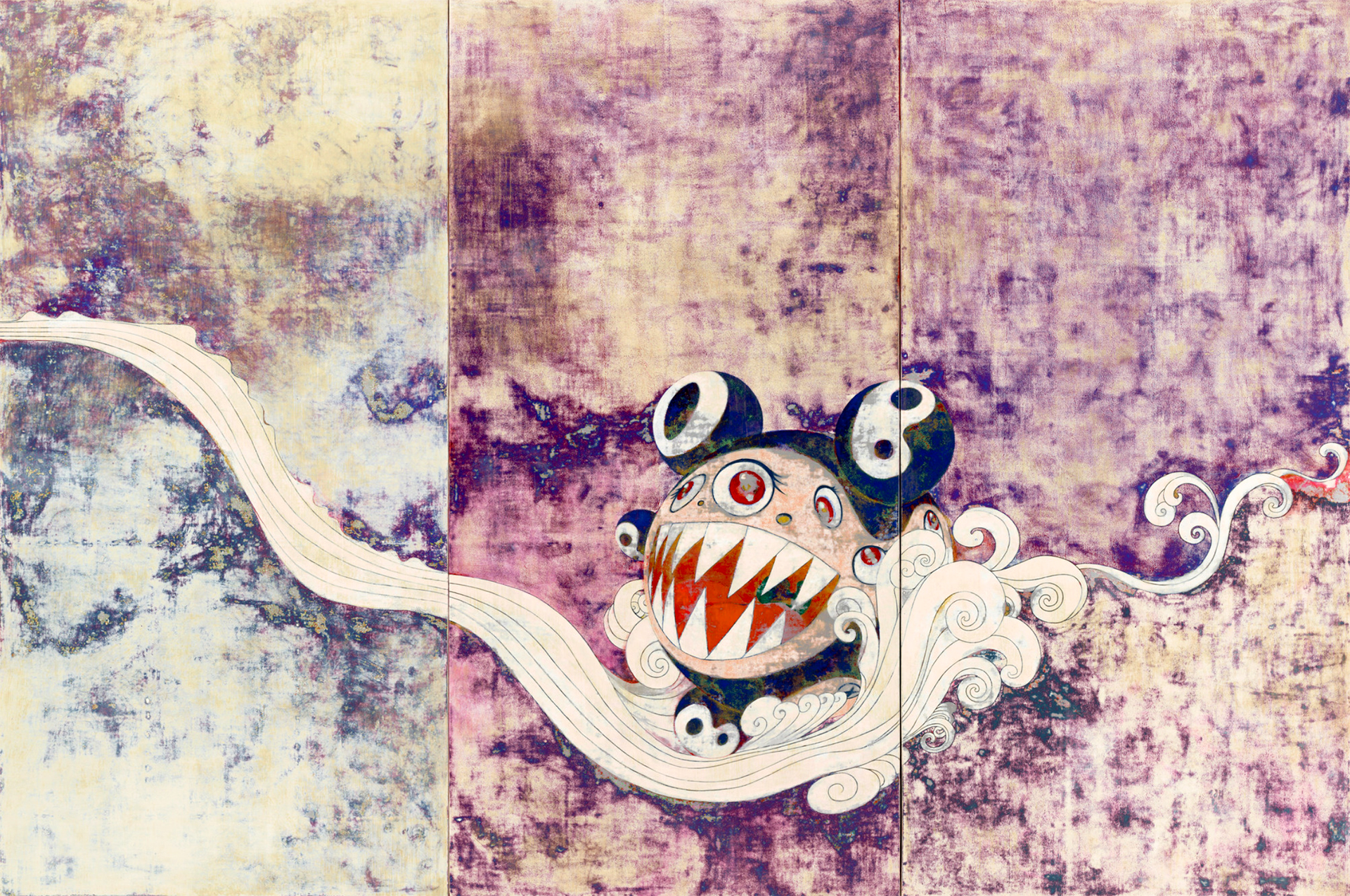

The influence and impact of American Pop Art is prominent in Japan. One of the most famous artists of Japanese Pop Art, Takashi Murakami, bases his works on traditional Japanese art, manga comics, and cheerful pop cultural imagery. However, under the bright facade, Murakami plants fear, anxiety, and sexual and violent impulses. Japanese Pop Art found its basis in the terror of the 1945 nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. For decades, cartoonish images helped to escape anxiety and channel fears into bold and loud creative expressions.