The Legalization of Christianity by Constantine the Great

How one fateful event ignited Rome's conversion to Christianity.

How one fateful event ignited Rome's conversion to Christianity.

Table of Contents

ToggleIn nearly one fell swoop, Rome went from practicing a long-standing polytheist religion to adopting a small monotheist faith that had previously been persecuted by the empire’s leaders.

The role of the conversion fell to that of Emperor Constantine I, also known as Constantine the Great. The rise of the emperor coincided with a well-worn tale about a mystic vision that led to his victory at the crucial moment of a Roman civil war. The effects of Constantine’s vision and his involvement with early Christian leaders left a legacy that still impacts the world today.

Constantine’s role in the future of the Roman Empire and world religion is one that still fascinates almost two millennia later. His status as a transformational figure is unique among Roman leaders and had an effect not dissimilar to that of Julius Caesar or Augustus.

Christianity was by no means the leading religion in ancient Rome. Rome had followed a religion with close ties to the earlier Greeks, including a pantheon that closely mirrored the Hellenistic gods.

However, Constantine’s actions would lead the empire to ditch Jupiter and Juno for Jesus.

Christianity’s origins take place within the Roman Empire, as Jesus of Nazareth preached in Roman Judea during the reign of Caesar Augustus. Following his crucifixion, a number of his followers believed that he rose from the dead three days later.

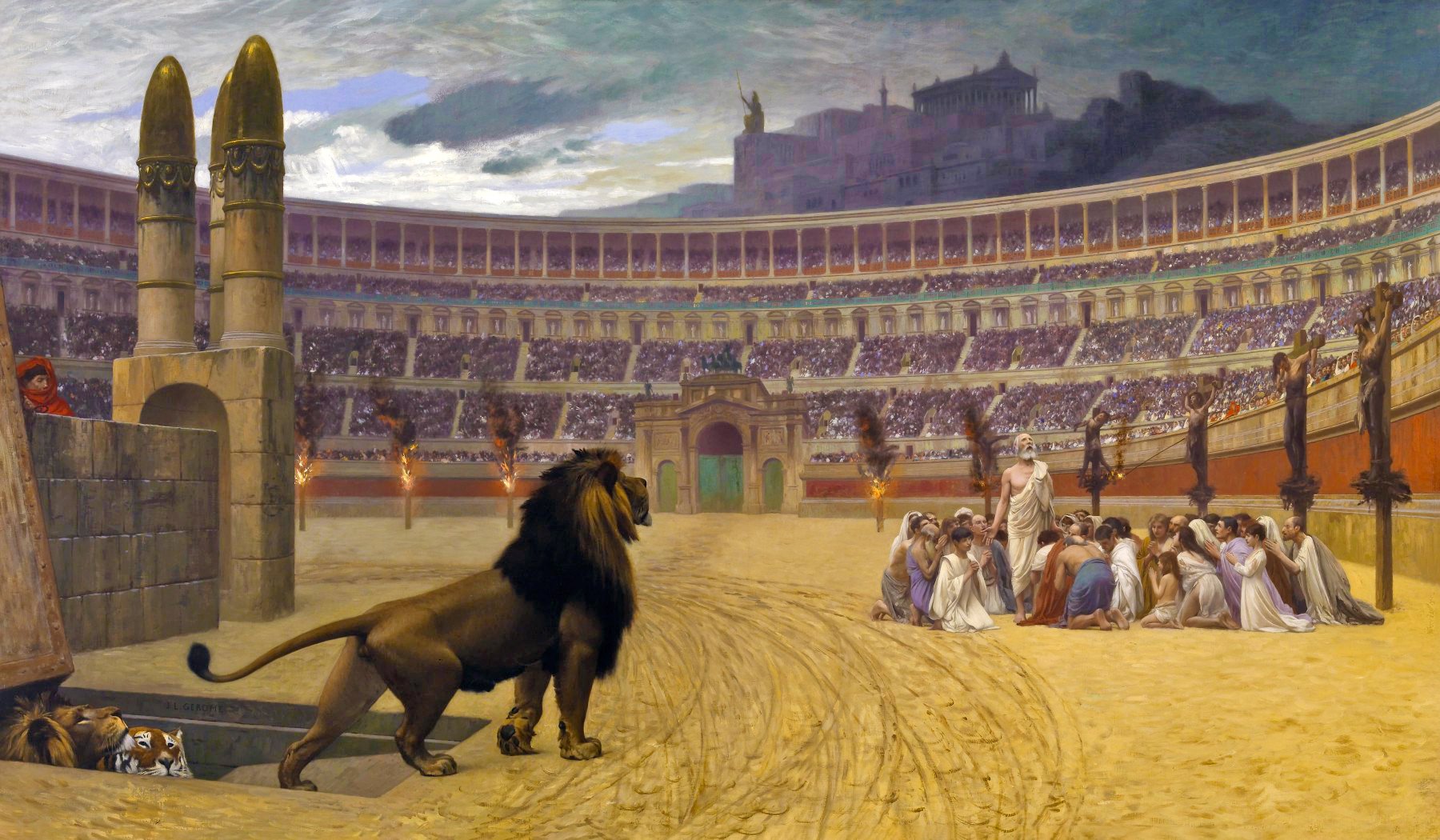

This offshoot of Judaism soon grew into its own faith and spread across the Roman Empire, where it was brutally repressed by Roman officials. During the reign of the Emperor Nero Christians were persecuted, despite representing a very small portion of the Roman population. In particular, Roman officials were offended by the Christian refusal to view the emperor as one of their gods, an issue not present with most polytheist faiths. By the time of Constantine’s rise to fame, Christians accounted for perhaps a tenth of the empire’s population.

So how did Christianity become legalized in the Roman empire? To answer that question, we need to understand the historical context that led to Constantine’s conversion.

In order to better understand how Constantine left such a large legacy, we must first recognize the challenges facing the Roman Empire prior to his ascension. The empire faced near-collapse in the 200s, during what historians call the Crisis of the Third Century. A period of rampant inflation, political assassinations, and civil war nearly broke the empire into pieces.

There were efforts to reverse the decline, including during the reign of Emperor Aurelian (270-275). However, the empire only began to patch itself together during that of Emperor Diocletian (284-305).

Diocletian believed that the Roman state, now spanning the size of the modern continental United States, was too large to govern effectively. He split the empire into four zones, known as the Tetrarchy, which was to include four rulers working together.

The emperor also made significant changes that helped usher in a system not dissimilar to the later Feudal System, reworking society to try and reverse the issues that plagued Rome for nearly a century.

Constantine’s father, Flavius Constantius was one of the four Tetrarchs intended to rule the empire in harmony. His mother, Helena, was a Christian.

However, after Diocletian retired in 305, the system fell apart and the empire fell into another civil war.

Constantine was an experienced Roman general by the time Diocletian stepped down. He was hailed as the rightful emperor by his troops, leading to him leaving his post in Britain to challenge the other leaders of the empire and eventually become the sole emperor.

Constantine’s early reign was marked by a partnership with the Emperor Galerius (305-311), ruling over much of the western part of the empire. However, a rebellion by the general Maxentius caused open conflict. Maxentius attempted to become emperor in 305 and fought a bitter civil war against Galerius, who died of illness in 311.

Maxentius held power in Italy and North Africa, leading to Constantine pursuing clever diplomacy to isolate the perceived usurper.

Following a number of victories against Maxentius’ forces, Constantine’s army approached Rome. Maxentius acted on behalf of what he claimed were omens from the Roman gods and prepared for a siege in the capital. According to Roman historians, Maxentius received word from religious figures that a prophecy foretold that in a coming battle “the enemy of the Romans” would perish.

Maxentius and his army traveled to challenge Constantine right outside of the city. Maxentius seemed to have a large advantage over Constantine, with his army outnumbering Constantine’s about two-to-one.

This is where the role of Christianity comes into play. There is still considerable debate over what exactly happened prior to the famous battle. There are several different versions of this story, so let’s review some of the particulars.

One version of the historical accounts suggests that Constantine saw a famous sign, the Christian Chi Rho symbol, in a vision. This symbol represented the first two letters of the word “Chris”’ in Greek, similar to the Latin letters X and P. Another account posits that Constantine saw a different vision on the day of his confrontation with Maxentius near the Milvian Bridge, a critical battle that would determine the future ruler of Rome. In this vision, he saw the words “In Hoc Signo Vinces,” which translates to “In this sign, conquer.”

Regardless of which account is more accurate, what is generally agreed upon is that Constantine ordered his soldiers to paint the Chi Rho symbol on their shields before the battle.

In the ensuing clash, Constantine’s forces won a resounding victory. Maxentius drowned in the Tiber River and his army was broken. Constantine was now in control of the western portion of the empire. Following another civil war more than a decade later, he would become the sole ruler of Rome.

The emperor’s role in the adoption and evolution of Christianity allows him to be seen as a saint by some of the faithful. Following Constantine’s victory he took some very different steps compared to his predecessors. He was acclaimed by the Roman Senate but ultimately did not make a sacrifice to the chief Roman god Jupiter as was the custom.

The emperor credited Christianity for his victory at the Milvian Bridge. He instituted one of the first, and by far the largest, ruling on religious freedom in the Edict of Milan of 312. In it, Christianity was legalized in the empire and its seized assets returned.

He was not formally baptized until the end of his life, but Constantine stated that he was a member of the Christian faith during his time as emperor. As a Christian ruler, he made tremendous efforts to promote the faith and is considered one of its most significant contributors to its eventual popularity.

During his reign, he aided with a number of major construction projects, including what would become the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the original St. Peter’s Basilica.

One of his biggest contributions to early Christinaity was conveying the First Council of Nicaea. The gathering allowed for the Christian leaders to declare belief in the Trinity of God, the Son, and the Holy Spirit and resulted in the famous Nicene Creed. The Council also allowed for the creation of a standard date for Easter and Constantine separately named Sunday an official day of rest.

![Symbolum Nicaeno-Constantinopolitanum. Icon depicting the First Council of Nicaea with ten men and a text of the Nicean Creed in Greek. The text in greek translates as:[title] The synod of the holy fathers,I believe in one god, the father the almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all that is, seen and unseen. And in one lord, Jesus Christ, the son, the only son of god, begotten of the father for all ages. light from light, true god from true god, begotten, not made, of one being [omo-ousios] with the father, through him all things were made. For us the human beings and for our salvation he came down from the heavens and he became incarnate out of the holy spirit and the virgin mary and man was made. He was crucified for our sake under pontius pilate. And he suffered death, and was buried...](https://www.culturefrontier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Nicene-Creed.jpg)

Constantine also created one of the key centers of both Christianity and the Roman Empire by founding the city of Constantinople (Greek for “city of Constantine”) in the former fishing village of Byzantium. Constantinople would serve as a new Rome and would become the capital city of the empire. The Eastern Orthodox branch of Christianity and its leader, the Patriarch, is based out of the city, today known as Istanbul.

Constantine’s victory at the Milvian Bridge is a crucial part of early Christian tradition. A number of Roman artworks and Christian icons depict either Constantine or the Chi Rho symbol. While many see the events of that day as a miracle, that may only be one interpretation.

Some historians cite an earlier incident that may better define Constantine’s motivations. Prior to his more famous vision, Constantine had claimed earlier that he saw the god Apollo, who is commonly tied to the sun. During this supposed vision, Constantine was promised 30 years of rule, which is about what ultimately occurred. The Roman historian Eusebius later credited the vision to that of the Christian God.

During Constantine’s reign and even following the famous battle, Constantine would often have himself depicted in the visage of Apollo or Sol Invictus. He built a triumphal arch dedicated to his victory at the Milvian Bridge which depicts the polytheist goddess Victoria and the god Sol Invictus, the Victorious Sun. Worship of the traditional Roman gods continued during his reign.

Historians still debate what the emperor saw prior to the battle. The multiple variations of the story make the exact circumstances difficult to pin down. It is possible that Constantine saw a “sun dog,” which is a reflection of sunlight that could look similar to the Chi Rho symbol.

Regardless of what Constantine saw that autumn day in 312, the effects still impact our world today. The Roman Empire became majority Christian and the faith became the official one of the empire by the end of the 4th century. Constantinople’s status as the capital of the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine, Empire, made the city crucial to global politics and to Christianity, until its conquest by the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

Through one man and his vision the world was changed forever near a bridge in Rome.