The Druids and Their Sacred Island

For thousands of years, the Druids have remained a mystery to the modern inhabitants of Western Europe.

For thousands of years, the Druids have remained a mystery to the modern inhabitants of Western Europe.

Table of Contents

ToggleFor thousands of years, the islands that sat at the furthest reach of Western Europe were inhabited by tribal groups who lived under the guidance of Druids. These Druids were known as wise and learned beings who had extensive knowledge of the arts, including astrology, mathematics, medicine, and divination.

The Druids, for centuries, were essentially unknown to most of the world. However, the few Mediterranean explorers and traders who visited the islands of what is now Great Britain and Ireland returned home with stories of these mysterious and highly sacred people.

Before Julius Caesar became emperor of the Roman Empire, he spent nine years on military campaigns in Gaul, a Celtic-speaking territory that covered modern France and parts of Belgium, Western Germany, and Northern Italy. He compiled his experiences of military campaigns throughout Gaul and the native peoples who lived there in eight books known collectively as De Bello Gallico.

In De Bello Gallico, Caesar writes of a people called the Druids. As the first time that Druids had ever been mentioned in a written text, Caesar’s description of the elusive Druids was not only informative but also extremely historically significant. Caesar defined the Druids as the priestly class, those who lived a life of “divine worship, the due performance of sacrifices, private or public, and the interpretation of ritual questions.”

The Druids, as Caesar described them, were exempt from war and instead spent their time studying divination, astrology, philosophy, and medicine. The Druids were educated by their own; in fact, Caesar wrote that they specifically didn’t want their “doctrines to be divulged among the masses of the people.”

One of the most fascinating aspects of Caesar’s writings on the Druids claims they were not taught on the mainland of the continent where he met them. Instead, they traveled a considerable distance west to be trained in the various arts on the shores of what many considered to be sacred islands, which historians now know to be the Isles of Ireland.

Over a century after Caesar’s important description of the Druids in Gaul, another text written by Latin scholar and traveler Tacitus mentioned these wise peoples once again. In the 2nd century CE, Tacitus recorded the Roman invasion of Anglesey, a small island off the coast of Wales, in his text, the Tacticus Annals. Tacitus wrote that as the Roman army approached the tribal settlement on the island, a collection of Druids raised their hands to the sky and began chanting in a manner that terrified the Roman soldiers.

Though scared of the Druids’ seemingly strange actions, the Roman soldiers prevailed. The Romans then decided that in order to disperse the Druids living there, they would destroy their sacred spaces. According to Tacitus, the Druids used groves for rituals, such as human sacrifice.

It’s clear the writings of both Caesar and Tacitus may have exaggerated the customs of the Druids in hopes of convincing Latin readers that these barbarians needed pacifying. Later native Irish and Welsh legends seem to tell a completely different story about the Druids.

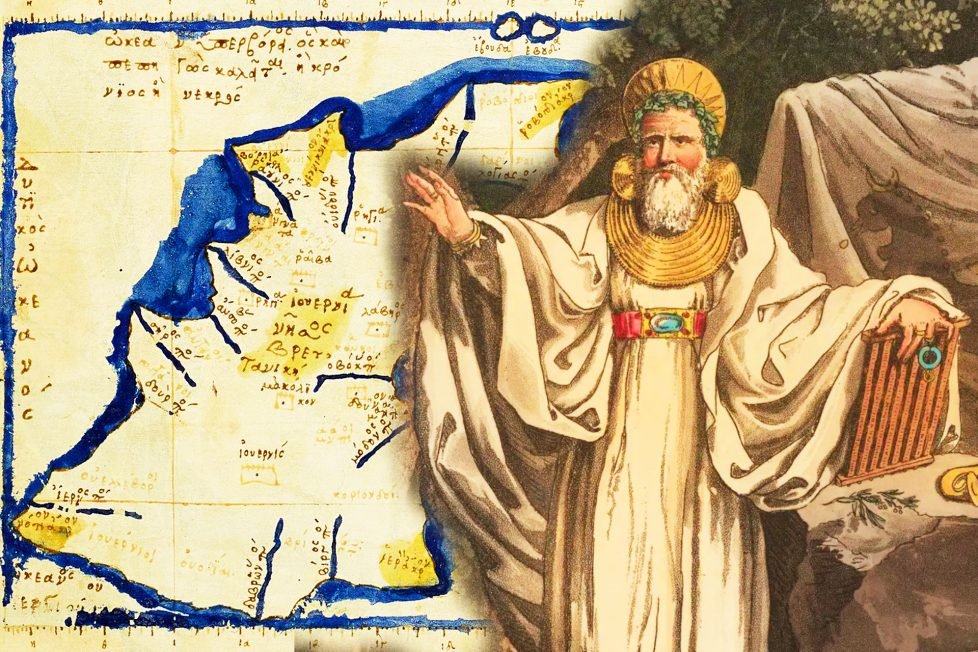

The Greek explorer Pytheas, who supposedly ventured to the isles of what is now Britain and Ireland in the 4th century BCE, wrote a detailed description of the land he encountered there.

Pytheas called the island of Ireland, Ἰέρνη which some scholars surmise derives from the Greek word ‘ἱερός’ meaning sacred. Though according to his writings, Pytheas never met the people of the island, and modern academics have no real indication as to why he considered it to be sacred.

But Pytheas wasn’t alone in his assessment; centuries later, Ptolemy of Alexandria calls Britain “Pretannaki” and Ireland the “Sacred Island of Pretannaki.” He assigns both ‘Mona,’ known today as Anglesey, and The Isle of Man as islands under the sovereignty of the Sacred Island of Pretannaki.

These two islands are now known to have been home to many Druids. The fact that Ptolemy connects them to the Sacred Island of Pretannaki, or Ireland, as opposed to Pretannaki, or Britain, may suggest that Ireland was the center for the education of Druids.

The suspicion that Druids were trained to deeply understand medicine, philosophy, and the arts on the island of Ireland has been supported by various texts from the 6th century CE onwards. At this time, the earliest written records centered on the history of Ireland were penned by sourcing written legends, manuscripts, and historical genealogies. They included various references to the Druids who lived on the island. According to surviving Irish manuscripts, the Druids were not an individual secular class but deeply respected and looked upon as mediators between man and god for the entire population.

Ancient Irish Druids acquired self-attained wisdom through experience and possessed a remarkable level of knowledge in natural philosophy and early sciences, including astronomy, spiritual theology, medicine, divination, and mathematics. But unlike the Gaulish Druids that Caesar encountered, the Irish Druids were also well-versed in the acts of war.

Both Caesar and the authors of the Irish manuscripts explain the Druids’ supernatural abilities in that they could predict future events. They report that Druids could retrieve information from a variety of omens, which would allow them to predict everything from the outcome of a war to how an individual’s day would go.

While the Druids were certainly paganistic polytheists, believing in and worshiping many gods, there is evidence to suggest they also believed in one supreme being that ruled over the others. According to the great scholar Manly P. Hall, the Druids worshiped a tree not as a physical entity but as a symbol of the one deity, the core of universal creation that was considered sacred above all else.

Modern historians have also learned a great deal about the ancient Druids of Ireland through Irish legends. Within these legends, the Druids held a position of trust within the individual tribes, and some stories even suggest they were ascribed more authority than the ‘Ri’ or tribal king.

A Druid of Ulster, Ireland’s ancient Northern territory known as Cimbeath, is spoken of in the surviving tale The Intoxication of the Ulstermen. In this legend, Cimbeath lives at the king’s court, and no one is permitted to speak, not even the king, until he permits so. This reiterates the previous idea that the Druids of Ireland were revered greatly and filled the role of mediators between god and the tribes, including the king himself.

Cimbeath is also known as a great teacher in the legends. In one version of the epic The Cattle Raid of Cooley, he gathered an extensive group on the grounds of the Ulster capital, Emain Macha. Here, Cimbeath enlightened those with his ‘Druidecht’ or Druidic science. All who wished to listen were invited to the gathering; however, only eight were said to have been taken on as pupils. In other texts, Cimebath is said to, at one time, have had as many as one hundred students.

The story of Cimbeath’s lesson to the masses proves that no particular class or sect was required to become a Druid. They openly taught any member of society, and those who could grasp the teachings would be taken on as students.

In texts regarding the Druids of both Ireland and Gaul, the Druids resembled shamans more, as opposed to priests. In fact, even the name Druids shows modern academics that these people were considered to have ultimate wisdom, as the Old Irish word ‘Drui’ means “wise one” in its truest sense, although this definition is contested. Most believe that ‘Drui’ literally meant “wise one,” some scholars have debated this definition. Max Muller believed the Irish ‘Drui’ is derived from ‘Dair’ meaning “oak tree.”

However, some argue that Muller only based his claim on the fact that Caesar mentioned the Druids of Gaul worshiped the oak tree. On the sacred island of Ireland, it was not the oak but the yew tree held sacred by the Druids. From its branches, ‘T’ shaped crosses were fashioned and inscribed with letters of the Ogham script, similar to how the Nordic peoples used Runes.

Other interesting differences are that the Irish Druids used the Ogham script, did not conform to a specific cast, and, most importantly of all, partook in wars. Whereas the Gaulish Druids adopted the Greek script, they were considered part of a higher class, and they refrained from fighting in any war.

The last mention of a Druid in a genealogical tract is the 4th-century king of the Cruithne and Ulster ‘Crunn ba Drui.’ His eponym, ‘ba Drui,’ is often translated as ‘one who was a druid.’

Crunn Ba Drui is said to have been a wise leader who protected the sovereignty of Ulster during an invasion by a petty king known as Murdeach Tireach. Crunn Ba Drui slew the invader himself, an event that some call exacting revenge on Murdeach, who had killed the former Ulster King, Fergus Fogha.

In legends, Fergus is said to have killed Colla Vais, a noble of the soon-to-be Christianized territory of Airgialla to the southwest of Ulster. According to the poem, Findaidh oidigh na Colla, found in the revered Book of Ballymote, Fergus “thrust his spear using sorcery.” Here, some scholars surmise that a later Christian writer was under the impression that Fergus had utilized some kind of Drudic force to kill the invader.

According to history, Ireland was first Christianized by Palladius, who was sent to the island by Pope Celestine in 431 CE; Saint Patrick followed a few years later. Together, these two men were responsible for converting the majority of the island, an act which led directly to the downfall of Druidism.

As Ireland was not a unified territory, the preachers were able to first convert various tribes living in the Irish Midland. However, an ethnic group known as the Cruithne living in the north was not interested in such a conversion and wanted to hold onto their Druidic beliefs. In fact, Saran, King of the Cruithne and son of Crunn Ba Drui, is said to have grudgingly opposed the teachings of the Catholic religion.

While it’s generally thought Saint Patrick brought forth a passive conversion, other sources suggest he was much more malicious in his actions. The Irish manuscript The Yellow Book of Lecan stated that during his attempt to convert the Druids, he burned nearly two hundred Druidic books. If this story is to be believed, it would mean that the Druids of Ireland did record portions of their history and mythology in writing even though they don’t exist today.

However, The Druids would not be defeated without a fight. According to texts, Patrick had to employ the help of another group that lived on the island known as the ‘Filid.’ Patrick could not have subdued the Druids without the help of the Filid, and in the centuries that followed, the Filid actually filled the roles once held by the Druids only in a Christianized form.

In the centuries that followed Saint Patrick’s conversion of the bulk of the Irish population, there was a divided culture in Ireland. Those who had taken on the customs of Roman Catholicism no longer looked to their Druids for spiritual guidance and, in time, even came to see their presence as evil or malicious.

The Druids were forced to seek refuge in northern territories that remained loyal to their guidance, and many decided to migrate across the sea into Northern Scotland. But one king from Ulster would eventually try to reestablish the ancient ways.

Congal Caech was born in Ulster during the 7th century CE; he went on to become the King of both Ulster and the ceremonial site of Tara. He was eventually ousted as King of Tara after he was blinded in one eye, as the laws of the time prohibited having a blemished king. Domnall, the King of the highly Christianized Ui Neill Dynasty, was crowned as the new King of Tara. Shortly after Domnall took on his new role, Congal declared that no one who took advice from a Christian priest should rule over Tara. The two kings then gathered their armies and went to war.

Congal’s forces were defeated, and he fled to Scotland to begin building a stronger army in hopes of reclaiming the territory of northern Ireland. Congal returned to Ireland seven years later with an army of Picts, Britons, Scots, and his native warriors from Ulster and began marching to Tara.

The battle of Magh Rath occurred on the eve of 637 CE and is often considered the largest in ancient Irish history. As the two armies finally stood face to face, a brutal battle ensued that lasted days. Unfortunately for the Druids, Congal was eventually slain, and with his death, Christianity was now considered the dominant belief system in Ireland.

There may be no better way to surmise the loss for the Druids with Congal’s defeat than what was written by the 19th-century poet Samuel Ferguson:

We are here upon the borders of the heroic field of Moyra, the scene of the greatest battle, whether we regard the numbers engaged, the duration of combat, or the stake at issue, ever fought within the bounds of Ireland. For beyond question, if Congal and his Gentile allies had been victorious in that battle, the re-establishment of old bardic paganism would have ensued.