8 Bizarre Medical Practices of the Middle Ages

Explore the stomach-churning medical practices of the medieval period.

Explore the stomach-churning medical practices of the medieval period.

Table of Contents

ToggleModern medical practices can sometimes seem horrific, but they’re nowhere near as gruesome as those used in the Middle Ages. The medical practices of the Middle Ages were often torturous and just as likely to kill you as they were to cure you.

Some of the techniques used by the quack doctors between the 6th and 15th centuries may have had a smidgeon of logic to them, but others bordered on the absurd. Bloodletting and the use of leeches were common medical practices in the Middle Ages. While no one would want a prescription for either of those two therapies, there were far more horrendous and grisly remedies for medieval afflictions that people had to endure.

You’d need to be feeling pretty bad to put your trust in a physician that wanted to use treatments like the ones you’re going to read about here. If you weren’t knocking on death’s door and desperate, guaranteed, you’d run a mile.

Getting drilled by a doctor in the Middle Ages had a completely different connotation to what it would have now. Instead of undergoing a session of quickfire questions about your health, the doctor would be preparing you for trepanning.

Trepanning has been practiced around the world since the Stone Age and involves boring a hole in the skull of the sufferer using a sharp, rounded instrument called a trephine. It was believed that trepanning would relieve any build up of pressure in the brain caused by an accident, that it could cure mental health problems and even release evil spirits from the bodies of those thought to be possessed by demons.

While you might think this barbaric treatment has been consigned to the annals of history, it hasn’t. Trepanning, or trepanation, is still used today to alleviate brain bleeds, but it’s now performed by a neurosurgeon with the patient under general anesthetic.

Those who were sainted by the Catholic church during the Middle Ages were often credited with performing miracles during their lifetimes. After their death it was believed that the saint’s relics, their body parts or on occasion their possessions, still retained miraculous healing powers.

Sufferers would travel miles to visit the churches where the saint’s relics were enshrined hoping that touching the blessed objects would cure their afflictions. Sometimes miracles did occur and after making their pilgrimage, some people recovered from whatever ailed them, but mostly they didn’t.

It’s no longer the Middle Ages, but every year millions of people still set off on pilgrimages to visit shrines where saint’s relics are interred seeking the miraculous. While the belief may be strong, the positive results are still pretty much on a par with medieval times – almost nonexistent.

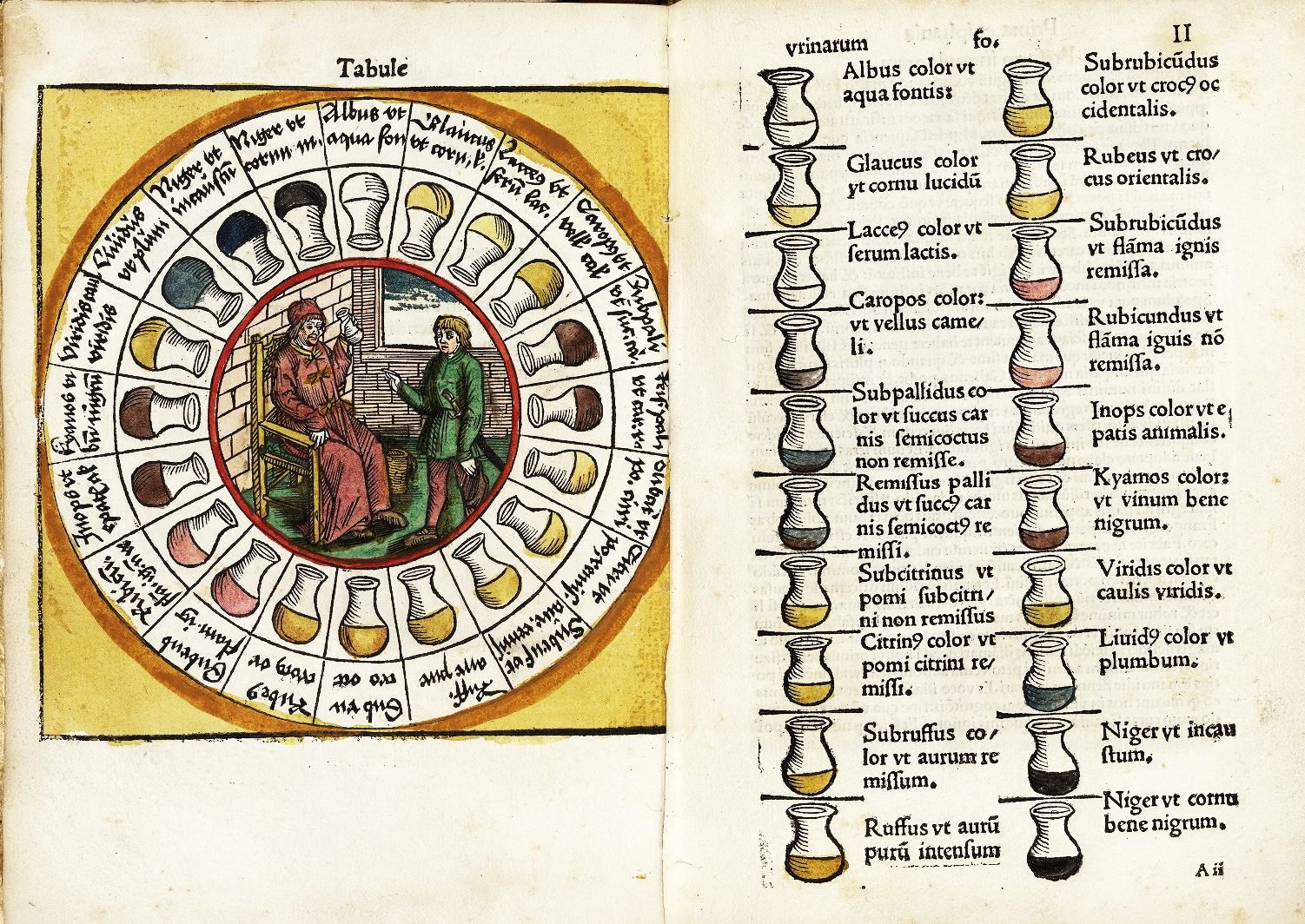

Giving a urine sample to a doctor to send away to a laboratory for analysis is a run of the mill medical procedure these days. In the Middle Ages doctors didn’t have laboratories to rely on, instead, like wine connoisseurs with a discerning palate, they would taste a patient’s urine in an attempt to diagnose what illness they were suffering from.

Not only was the taste of the urine taken into consideration, but the color and smell as well. While uroscopy, diagnosing illness by examining urine, was a centuries-old medical practice even in medieval times, it was during the Middle Ages a diagnostic tool known as the urine wheel was introduced. The wheel was a circular diagram that aided practitioners to match a variety of urine colors, smells and tastes to twenty different afflictions of the time. It may sound simple, but in the Middle Ages it was a major medical advancement.

The same word can mean different things in different languages and translations can often turn out to be erroneous. That’s something that happened in the Middle Ages with one of the popular cures of the time.

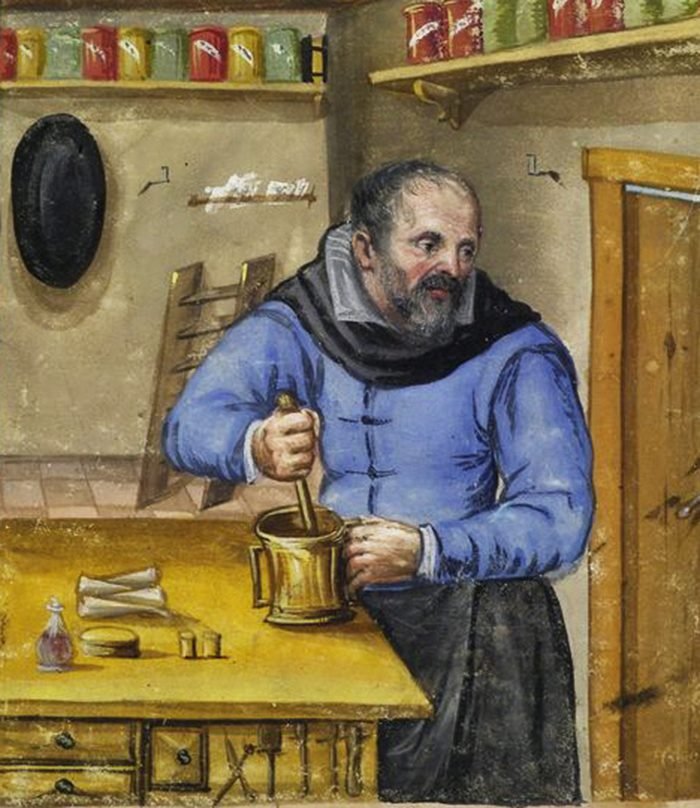

Bitumen, mummia or pissaphalt, a natural black mineral from Western Asia, was used as a cure-all in medieval times. As time progressed and its use spread to Europe, the pharmacists of the time thought the name of mummia referred to a mummified body and ordered imports of a bitumen-like liquid excreted by Egyptian mummies.

They also took a liking to mummy powder, made by grinding up desiccated dead bodies, which they gave to their patients to consume as a remedy for just about anything that ailed them. Not surprisingly, there weren’t enough mummified or dried out bodies to meet with the increasing demand so many of the apothecaries would make their own mummia by stealing corpses, chopping them up and drying them out in kilns. This gruesome custom for consuming human remains didn’t go out of fashion until well after the Middle Ages had come to an end.

Doctors of the Middle Ages didn’t have treatments like antibiotics to combat wound infections, but by the late 14th century they’d discovered something that would do the job quite efficiently – given time. What they discovered that worked so well was maggots. Yes, those squirming, wriggling white larvae that left to their own devices to fulfill their life cycle will eventually turn into flies.

Maggot therapy has been used by civilizations as ancient as the Mayans. Its beneficial properties were rediscovered by accident on battlefields after soldier’s injuries became fly-struck. It was noted that rather than being detrimental to health, the hatched maggots consumed the infected dead flesh and promoted the healing process. While it may make you cringe just to think about it, maggot therapy is still used today to treat ulcerous wounds and the removal of dead skin tissue.

Dung ointment is one medieval remedy that would have left you heaving as it was exactly as the name suggests, an ointment made from animal excrement. Medieval physicians would prepare unguents using just about any kind of animal feces they could get their hands on and if none was available, they weren’t averse to substituting it for the human variety either.

The animal dung would be mixed with ingredients such as eggs, lard or wax to create a poultice that was applied to infected wounds. While it may seem improbable, the dung ointment was relatively successful as the feces contained micro bacteria that acted on the infection in a similar way antibiotics would. It just smelled a lot worse.

Dwale was one of the earliest forms of anesthetic to be used. Administered in liquid form, dwale was more of a witch’s brew than it was a medicine. This strange concoction used in the Middle Ages to send people to sleep before they were operated on contained curious ingredients like pig’s bile, hemlock juice, lettuce, opium and vinegar.

When combined together, the ingredients of the concoction had both sedative and pain killing properties, but was also highly poisonous. The potency of the hemlock and opium was increased even more as dwale was usually mixed with copious amounts of wine when it was time to administer it. While the use of dwale in the Middle Ages is relatively well documented, what’s not documented is exactly how many people woke up after taking it.

In medieval times doctors didn’t just rely on their skills to perform successful surgery, they consulted the stars to make sure they were in the right alignment before commencing with the first cut. While astrological knowledge was very limited, physicians believed certain planets and constellations influenced certain parts of the human body. They also believed the position of the planets in the solar system altered the effectiveness of the plants and herbs they used in their remedies.

As if all of that wasn’t complicated enough, they relied on signs of the zodiac to aid them with diagnosis. For example, if someone fell ill in mid-March then their affliction would be controlled by the sign of Pisces which related to the lymphatic system and they would be diagnosed accordingly even if they had something else entirely.

Medical practices in the Middle Ages were definitely hit and miss. Sometimes they worked, but more often than not, they didn’t. They were spine-chillingly gruesome and on some occasions, were downright torturous. In the Middle Ages you didn’t just go to the doctor in order to survive, you needed to survive going to the doctor’s too.