Who Wrote Shakespeare’s Plays? (Spoiler: It’s Shakespeare!)

Let's settle the Shakespeare authorship question.

Let's settle the Shakespeare authorship question.

Table of Contents

ToggleIn 1920, John Looney, a British school teacher, published a book called Shakespeare Identified, in which he claimed that the actual author of the plays of Shakespeare was Edward de Vere, the Earl of Oxford. While he was not the first to posit a different author for the plays and sonnets, in the past hundred years his theory has continued to attract many adherents, including Sigmund Freud, Sir Derek Jacobi, and United States Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia.

However, despite their best attempts, there are still some very strong arguments in favor of the Stratford man William Shakespeare.

William Shakespeare was born on April 23, 1564, and baptized Gulielmus Shakespeare. He was the son of John Shakespeare, a glover and alderman, and Mary Arden, who came from a Catholic family involved in some plots against the Protestant Queen Elizabeth. As the son of a prominent citizen of Stratford, it’s very likely that he attended the Stratford grammar school, where he would have learned Latin and rhetoric. In 1582 he married Anne Hathaway, who was several years older than him, and their daughter Susanna was born six months after the wedding. Three years later, their twins Hamnet and Judith were born.

By 1588, Shakespeare probably arrived in London, and the next year his first play, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, was performed. In 1592, a rival playwright described him as “a player wrapt in a tiger’s hide”. The following year, Shakespeare’s theater career took a hit when an outbreak of the plague shut down London theaters. He switched gears and wrote a poem, “Venus and Adonis”, which was published by Richard Field, a London printer who had grown up in Stratford. In 1594 the theaters reopened, and Shakespeare joined the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, a prominent acting company led by the actor Richard Burbage.

Shakespeare experienced considerable success but also personal tragedy in the succeeding years. In 1596 his only son Hamnet died, the same year that Shakespeare was granted permission to use a coat of arms. In 1597 he bought New Place, the second-largest house in Stratford, for £60, which was the equivalent of four years’ wages for a skilled tradesman. In 1603, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men became the King’s Men when James I, the new king, became their patron.

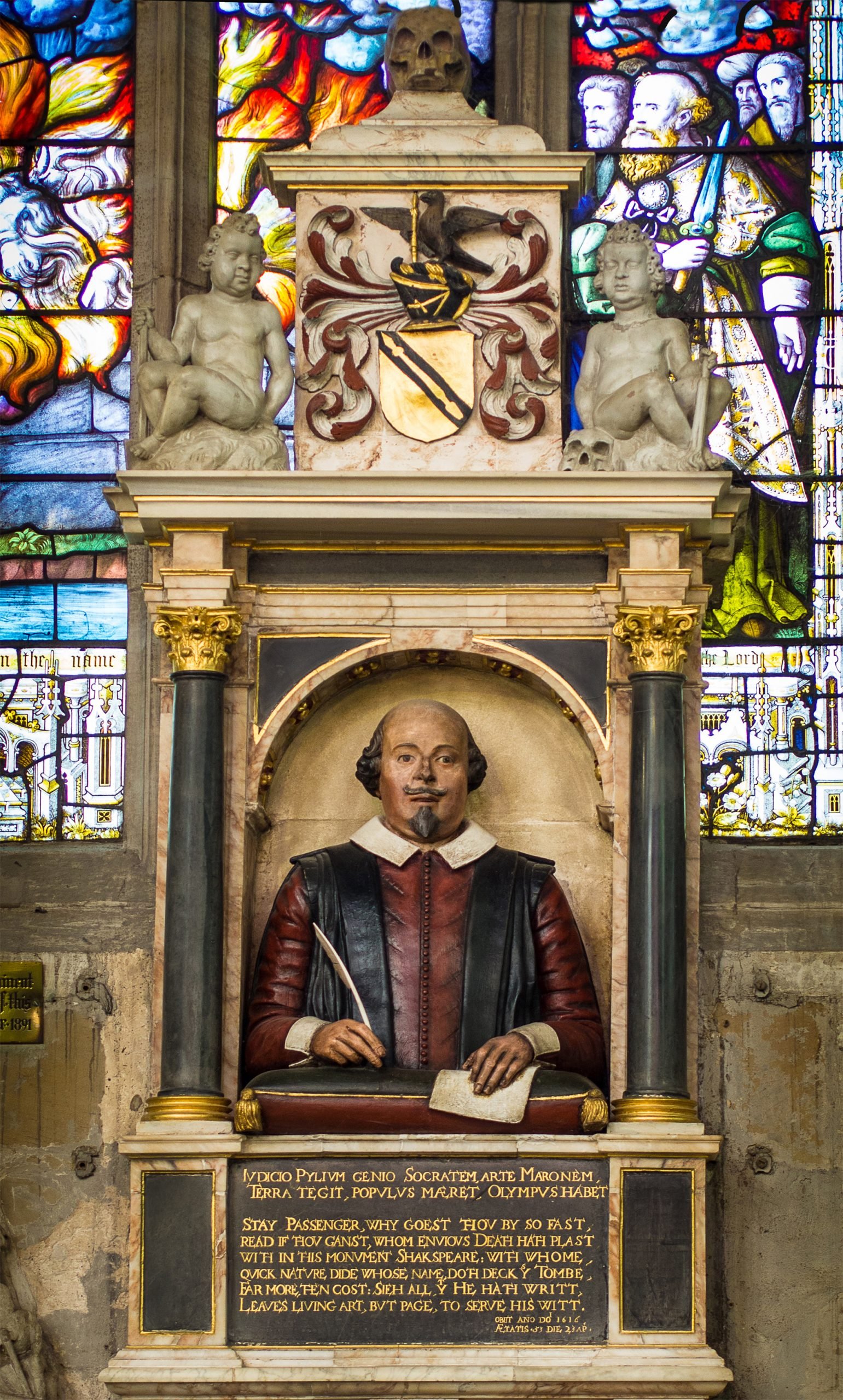

Possibly suffering from ill-health, Shakespeare returned to Stratford for the last few years of his life. He died on April 23, 1616, and was buried in Holy Trinity church in his hometown. In 1623, two of his theater colleagues, John Hemynges and Henry Condell, published his collected works in what is now called the First Folio. Ben Jonson, a fellow playwright, wrote a eulogy calling his late friend “The Sweet Swan of Avon”.

Sir Francis Bacon, Lord Chancellor in James I’s reign, was first suggested as a possible author in the nineteenth century. It was claimed that he had to write the plays anonymously so that he could aspire to high office, as writing plays was considered low-class.

Later, others touted the claims of Christopher Marlowe, one of the most celebrated playwrights in Elizabethan England. While scholars have recently determined that Marlowe did have a hand in writing all three of Shakespeare’s plays on the reign of Henry VI, he died in 1593, long before most of Shakespeare’s greatest plays were performed.

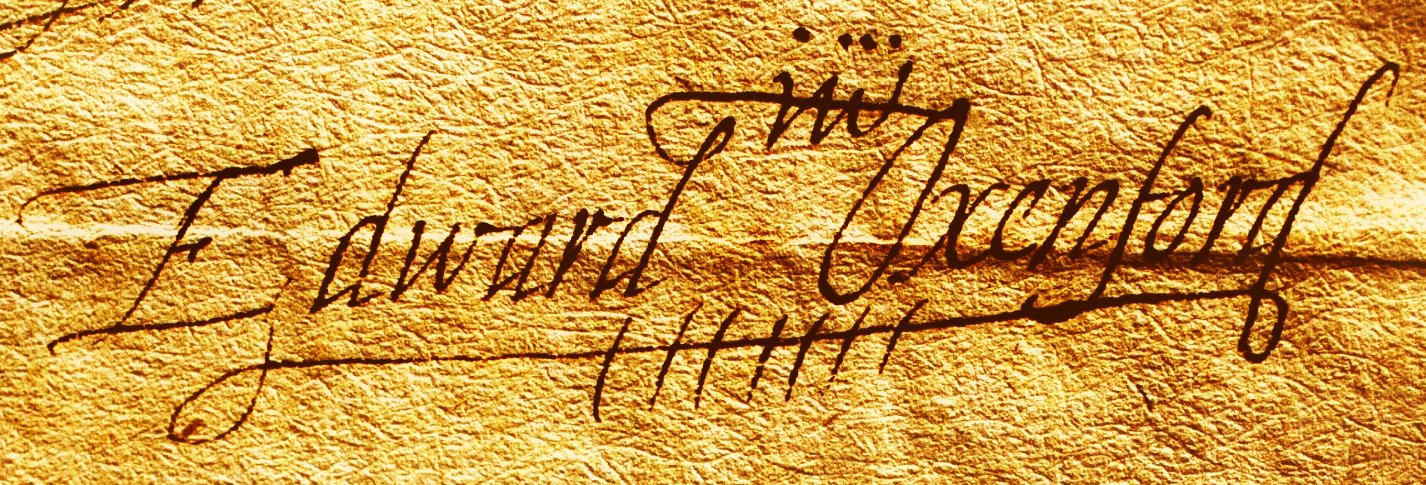

Finally, we have the current favorite candidate for the role of Shakespeare, Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. Since Looney’s book was first published in 1920, those subscribing to this authorship theory have pored over not only the works themselves, but also the life stories of the two men in their zeal to prove that Oxford was the author of what we know as Shakespeare’s plays and poetry.

Edward de Vere was born on April 12,1550. He became a ward of Queen Elizabeth after his father’s death in 1562, and was raised in the household of Sir William Cecil, Elizabeth’s most trusted courtier. He later married Cecil’s daughter Anne, but it was not a happy marriage, and they were estranged for five years. He was even jailed in the Tower of London in the early 1580’s for getting one of the Queen’s maids of honor pregnant. Around the same time, he was accused by several boys of repeated rapes over the previous decade.

Profligate with money as well, he sold off many of his family’s lands, and by 1586 Queen Elizabeth had to grant him an annuity of £1000 to keep him afloat. He continued to sell more property, and in the 1590s tried to get the Queen to grant him a monopoly to the tin mines of Cornwall. While he failed in this, he ended his life in rather more stable economic circumstances. James I succeeded Elizabeth on the English throne in 1603, and soon granted Oxford the Forest of Essex and appointed him the Keeper of the Palace of Havering, as well as continuing the annuity first bestowed by Elizabeth. Less than a year after participating in the new king’s coronation, he died on June 24, 1604.

The Oxfordian argument is that Edward de Vere simply had the education, travel experience, and social standing that the author of the plays would have needed.

He was taught by private tutors, one of whom said after eight months that “I clearly see that my work for the Earl of Oxford cannot be much longer required”. De Vere received honorary degrees of Master of Arts from both Cambridge and Oxford, and studied law at Gray’s Inn.

Oxford traveled extensively in France and Italy in his early adulthood. Italy was the setting for several of Shakespeare’s plays, including The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Romeo and Juliet, and The Merchant of Venice. He then returned to England and took up a place at court as the current holder of the second-oldest earldom in the kingdom. Many of Shakespeare’s plays are set in royal courts.

Some of his poems survive, but although he is mentioned as an author of plays, no copies of any in his name have survived. He did have a keen interest in the theater, and was the patron of an acting company in the 1580s. Still, while sponsoring a troupe of players was considered appropriate for an aristocrat, writing plays was considered beneath his dignity, so he could not publish works under his own name and maintain his social standing.

On the other hand, Oxfordians point to the dearth of proof regarding the education of “the Stratford man”. Shakespeare probably never traveled outside England, and coming from a middle-class background, he would not have been familiar with the ways of royalty.

There are many reasons why Edward de Vere is unlikely to be the author of the plays of Shakespeare, but we’ll just focus on one main issue: when he died.

Oxford died in June 1604, after James I had ascended the throne, but well before Guy Fawkes tried to blow up Parliament, along with the king, on November 5, 1605. He failed in that assassination attempt, of course.

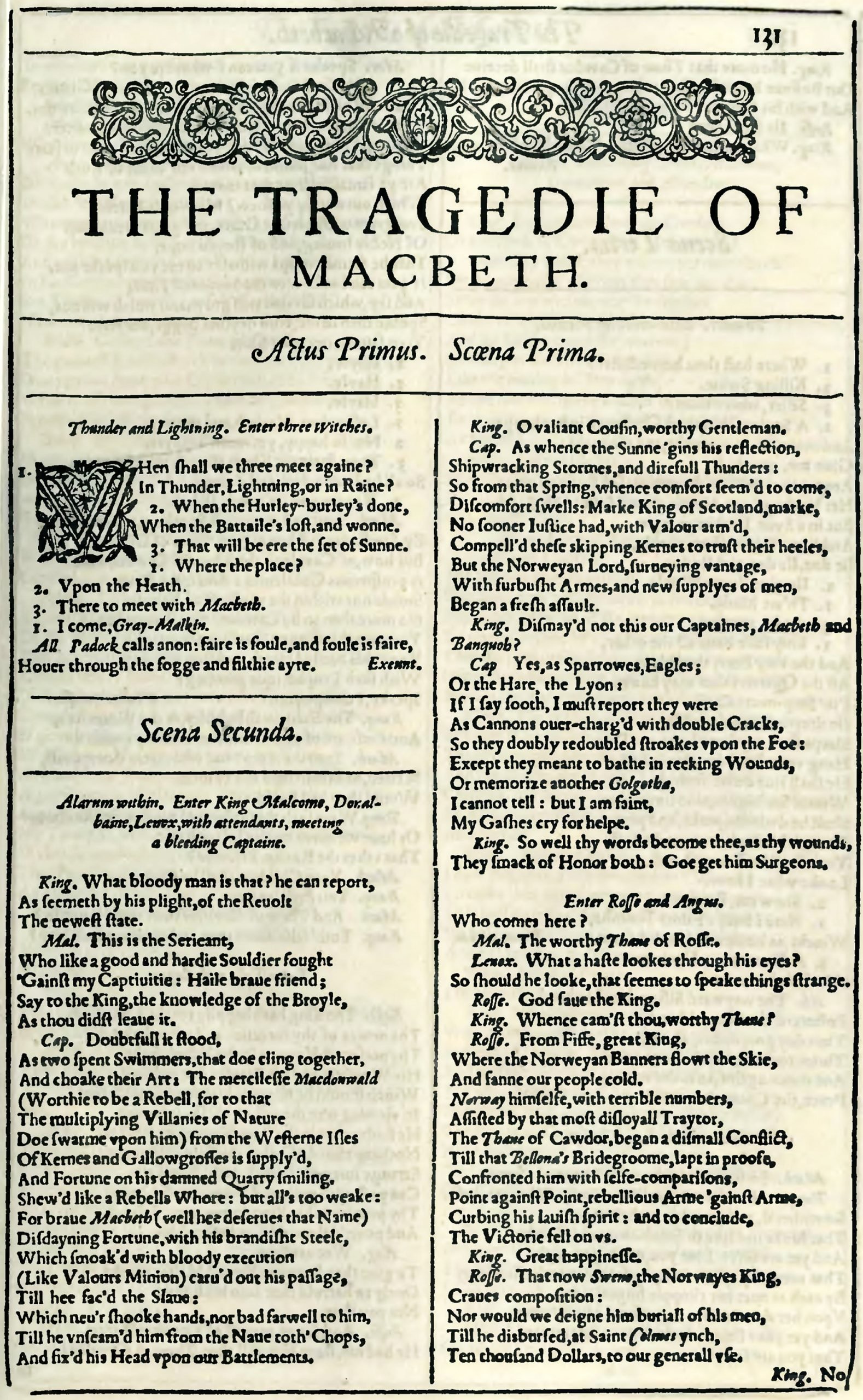

Macbeth, Shakespeare’s play about the dire consequences of killing a king, was first performed for King James in either August or December 1606, more than two years after Oxford’s death. The Oxfordians have postulated a date of 1588 for this play, claiming that the assassination that it was inspired by was that of Lord Darnley, the husband of Mary Queen of Scots and father of King James, in 1567.

However, an examination of the text makes it clear that it’s very much focused on the new king and his interests, as well as references to the Gunpowder Plot that would have been very obvious to a contemporary audience.

Witches were an obsession of James I. In 1590, his bride, Anne of Denmark, had to abandon her voyage to Scotland because of fierce storms, and when he traveled to fetch her himself, he found that the common belief in Denmark was that witches had cursed the journey, and several women there were executed. Back in Scotland, James started his own witch hunt. Over 100 people were put on trial, and many were executed. In 1597 he wrote a book called Daemononlogie on the subject of witches. In Macbeth, the witches are integral to the plot and theme of the play, and in fact boast of cursing a ship at sea: “Though his bark cannot be lost, Yet it shall be tempest-tossed.” (1.3. 25-26).

Lady Macbeth urges her husband to “Look like the innocent flower, But be the serpent under’t.” (1.6.76-77). Anyone watching this play in the aftermath of the Gunpowder Plot would recognize that as a reference to the coin struck to commemorate that event.

Finally, there’s the vision of future kings that the witches show to Macbeth, descended not from him but from the murdered Banquo, “ending with some I see/ That two-fold balls and treble scepters carry” (4.1. 120-121). As king of both Scotland and England, James had the orb and scepter of Scotland, as well as the orb and two scepters of the English regalia.

It’s impossible that a play so steeped in the events of 1605 could have been written by a man who died the year before. While this isn’t the only proof that Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare, it’s enough to make clear how tenuous the claims of the Oxfordians are.